You have been on Samos for three years. How has the situation evolved since then?

Sadly, the situation keeps getting worse. Since March 2016, when the deal with Turkey was struck, an increasing number of people have crossed the Aegean Sea and remained stuck on five Greek islands (Lesvos, Samos, Chios, Kos and Leros) waiting to receive the necessary documents to be transferred to the Greek mainland or be deported.

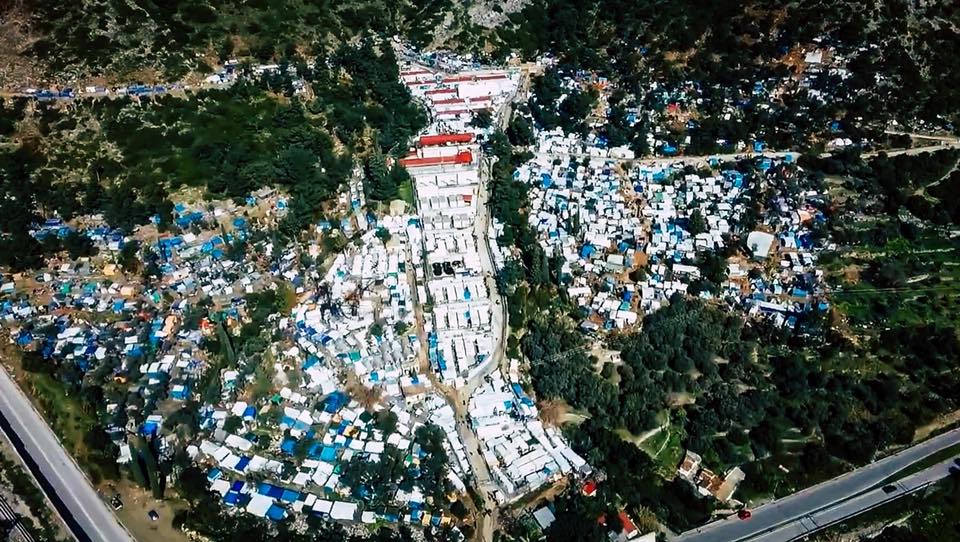

Over the years the situation on these islands has grown ever more tense: at the moment on Samos there are around 6,000 people in a camp meant to house 650. Housing in containers ran out years ago, so the new arrivals have to get by either by buying a tent or building themselves a wooden structure in the so-called ‘jungle’ – the zone of informal housing around the camp. There are no showers in these areas and the only toilets are chemical toilets built by MSF [Doctors Without Borders], not by the authorities.

In Samos there is only one structure for unaccompanied minors, so about 250 live in the camp or the jungle, without support. Pregnant women, single women, and children are left to themselves. It often happens that women give birth in the camp; the ones that make it to a hospital are then often sent back, to a tent, with their new-born.

Victims of physical or sexual abuse cannot be protected: even having reported their aggressor, there is no safe space where the victim can be transferred to, so they are forced to live in the camp, without protection.

What is the current situation for refugees?

At the moment (June 8th, 2020) there are around 6,000 people in the Samos hotspot, which as I said was built with a maximum capacity of 648 people.

Despite the fact that movement restrictions brought in in light of COVID have been lifted in Greece since the 4th of May, the hotpots on the islands remain in total lockdown. This is the case even though in Samos there have been no reported cases of COVID-19 in the local population or among the residents in the camp. This means that already limited services have now completely disappeared.

Greece has handled the pandemic very well, with fewer than 3,000 official infections and only 180 deaths in the entire country. The government’s strategy to “protect” the refugee camps, however, is simply to keep people locked indoors, where no kind of social distancing or hygiene is possible. In at least three camps on the mainland, with confirmed cases of COVID-19, the solution has been to put the camp on lockdown and nothing more.

Moreover, from the start the government has decided that those who have received refugee status for more than a month have to leave their housing and have no right to the pocket money provided by UNHCR with European funds. This means that thousands of vulnerable people are ending up on the streets because they have no other option. This is due to the fact that integration programmes are minimal in Greece: other than the HELIOS programme of the IOM (International Organization for Migration), which is difficult to access because of bureaucracy), there are only a few NGOs in parts of Greece that work seriously on integration.

This means that asylum seekers often spend months of hell on the islands in inhumane conditions before they are transferred to other camps on the mainland where life conditions are better. These mainland camps, however, are often located in isolated places where the possibilities to learn languages or for children to go to school are non-existent. After one or two years of waiting without doing anything, stuck in the middle of nowhere, they are left on the street. I have many former students, now 18 years old, and other adults I know, that are in this situation.

Can you tell us any particular episodes that have struck you and that you were engaged in?

Throughout these years I have met the best and the worst of humanity. The most difficult situations are those that involve unaccompanied minors, children that arrived here alone and without protection or support. One of them had a very difficult past (like many of them, sadly) and, after having lived for a few months in a tent in the ‘jungle’ attempted to take his own live. He was brought to hospital and his injury was treated, but because there was no safe space to house him, he had to stay on the floor of the police station for ten days, with an air mattress and sleeping bag. That was the safest place they could find for him. Because there is no psychiatrist for minors in Samos, he was transported for a day to another island for an appointment that lasted 15 minutes. After that, he was simply sent back and released back into the camp without any follow-up or support. With the support of a group of lawyers, we applied to ECHR (European Court of Human Rights) for an immediate transfer request. The request was granted, but only took place two and half months later.

In the midst of these daily tragedies, however, there are also moments of joy. For the greatest part, these children are smart, kind, caring and very altruistic. Two of them, D. from Cameroon and O. from Syria, have been with us for almost a year and have become great friends. They are very diligent students, have covered the interior of the container with post-its with English words on them that they can repeat every night before going to bed; in a short amount of time they were able to join our advanced English class and now speak the language fluently. They both left Samos more than a year ago: O., after months of pain and torture on the Balkan Route, is now in Germany. Obviously he has covered the wall of his locker with German words and already speaks the language better than me. D. has stayed in Greece in a structure for unaccompanied minors: he plays professional football, speaks Greek fluently and has finally received the documents he needs to stay.

These are the children we fight for: they have lost so much and faced the impossible when they were very young. All that they ask for is the chance to have a normal life.

What is the status of Still I Rise’s projects in Greece and in other countries?

In Greece, in Samos, we have a youth centre for children aged 12 to 17 living in the hotspot. In August our centre Mazì (which means ‘together’ in Greek) will have been open for two years. Finally, after three months of lockdown due to COVID-19, we are able to open up again! Despite the fact that all of Greece has lifted the lockdown on the 4th of May, and that Greek children have returned to school on the 25th of May, in the hotspots on the islands the lockdown will remain in place until at least the 21st of June. We have had to apply for special permission from the camp manager to allow the children to come to our centre. Luckily, the permission was granted.

The school in Turkey is ready, but it is still closed due to the pandemic: we hope to be able to open it in September! We also hope to open in Syria in about a month’s time, but it depends on the building works going on. In Kenya we are still in the early stages. Unfortunately, the pandemic has upset all of our plans, so we keep re-evaluating and adapting our projects week by week.

What drove you to start this activity?

The injustice. I left home and moved to Samos because I wasn’t able to read, listen, look at what was going on to these people in my Europe without doing anything. Mazì was borne from this: fighting the injustice of the refugee camps and bringing back the basic rights of children, at least in our centre.

It is absurd that a piece of paper like a passport can constitute such a divide between having all the fundamental rights that, for example, we enjoy as Italian citizens, and being treated worse than animals simply for having the misfortune of being born with the wrong passport.

In Europe, which prides itself of being the land of democracy, freedom and rights, this is unacceptable. I could not continue to enjoy my rights, always taken for granted and for which I never had to fight, when other humans like me are treated as sub-humans. Often my students tell us that in Europe animals have more rights than they do: if you find an injured and malnourished dog on the street you feed it, you bring it to the doctor, you find it a place to stay, but not to them. This is completely absurd.

What gives you the strength to continue keeping your activities going amidst all the difficulties and injustices?

My students and knowing that I am on the right side of history. Despite all the difficulties, the injustices and the terrifying situations I see, I tell myself that I am lucky it is not me, or my family, who have to endure them. Unfortunately, it is difficult to make miracles happen, but even just knowing that you have helped one person means you have made good use of your life. And so we continue!

Other than the drone shot, all the photos were taken by students of Mazì as part of the project “Through our eyes”. https://www.stillirisengo.org/en/projects/exhibition/

Translation from Italian by Davide Schmid and Gemma Bird