A belief in far-fetched ideas that help us make sense of crises ultimately feed regressive and right-wing politics.

By Sonali Kolhatkar

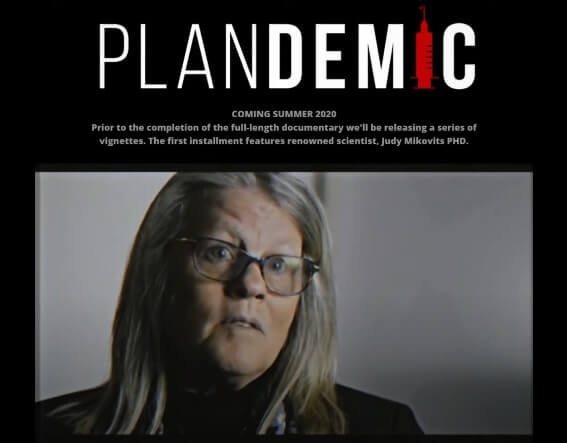

A mysterious new video documentary, slickly produced, and offering answers to the coronavirus pandemic, has been viewed millions of times on the internet in spite of the fact that various platforms have repeatedly removed it. The “Plandemic” video is, according to the BBC, “filled with medical misinformation,” and claims that, “the virus must have been released from a laboratory environment and could not possibly be naturally-occurring; that using masks and gloves actually makes people more sick; and that closing beaches is ‘insanity’ because of ‘healing microbes’ in the water.” It offers a scientific and authoritative-sounding basis for the far-right anti-lockdown activists protesting across the country, some of whom are even holding up signs that say “Plandemic.”

Why do so many people believe in vast and incredible-sounding conspiracy theories? Psychologists have attempted to answer this question for years, and some have suggested that moments of crisis and the resulting stress humans feel make us more susceptible to accepting far-fetched claims as we try to make sense of the world. One published studyin the journal of the American Psychological Association found that, “more stressful life events and greater perceived stress predicted belief in conspiracy theories.”

While choosing to believe in conspiracy theories may result in the believers feeling empowered with knowledge that only they have, the consequence of a collective belief in nonsensical ideas usually results in regressive policies. It hampers progressive political organizing and undermines the credibility of the left. It more often than not feeds into right-wing ideas and policies.

In the case of the “Plandemic,” the discredited scientist at the heart of the film, Judy Mikovits, even thanked President Donald Trump on Twitter for throwing the nation’s leading infectious diseases expert Dr. Anthony Fauci under the bus and, like so many of Trump’s own supporters, repeatedly attempts to undermine Fauci. Mikovits’s bizarre and dangerous theories about the origins of the virus echo Trump’s own idea that China created the COVID-19 virus in a lab. She continues to be interviewed widely about the film as per her Twitter feed, suggesting that the film continues to be promoted.

Nearly two decades ago, when the U.S. was hit by the earth-shattering events of September 11, 2001, Americans similarly were drawn to wild conspiracy theories that coalesced around what came to be called the “9/11 Truth Movement.” The idea that George W. Bush’s administration was somehow in on the horrific terrorist attacks that killed thousands of Americans was apparently a comforting thought to those who simply could not accept that they were inspired by the blowback of decades of destructive American foreign policy. In the years following the attacks, millions of Americans watched and shared the film “Loose Change,” which was held up as a central document of the “truther” movement.

Ten years after “Loose Change” was released, its filmmaker Dylan Avery explained his motive for making the film, saying:

“September 11 was ‘welcome to the real world,’ for me. My best friend was overseas fighting this war that was a direct consequence of this event, and that’s one of the main things that drove me during those years. If I could somehow raise awareness that this event was fraudulent or faulty, maybe my friend could get home quicker… I was angry about something at the time, and that was my way of expressing it.”

Avery even admitted that one of the main claims of the film—that footage of Osama bin Laden was fake—may have been because, “What I think happened was the aspect ratio got screwed up, and when the footage was put on the internet, he looked fatter.”

One of the most prominent proponents of the “9/11 truth” movement was Alex Jones, the now-discredited media figure behind Infowars who has promoted dozens of wild theories that his followers take seriously. Among his believers was a presidential candidate named Donald Trump, about whom Jones said, “It is surreal to talk about issues here on air and then word for word hear Trump say it two days later.”

But plenty of people on the left are also routinely seduced by films promoting conspiracy theories. In fact, “Loose Change” first gained widespread traction on the radio station where I work, KPFK—a fact that is mentioned on the Amazon listing of the film (yes, it is still listed there). Recently, since the release of “Plandemic,” I have gotten several emails from listeners of my show on KPFK asking me to watch and cover the film—which is incidentally where I first heard of the dubious documentary.

Conspiracy theories offer an easily digestible worldview that helps to make sense of our perplexing circumstances. But they are destructive and antithetical to constructive political organizing. Imagine if the energy wasted on believing that “9/11 was an inside job,” had instead been poured into fixing American foreign policy in the Middle East. Claiming that the attacks were a pretext for the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq has done little to actually end those wars. It has simply enabled “9/11 truth” believers to congratulate themselves on having the inside scoop on the most harrowing American event in recent memory.

Today’s anti-vaccination movement that bases its belief in the dangers of vaccines on the profit-motives of the pharmaceutical industry has actually done little to hold that industry to account. It has simply resulted in growing numbers of Americans withholding vaccinations of their children, which in turn has helped previously eradicated diseases like measles to return and endanger the most vulnerable among us. In fact, while the world waits for an effective vaccine against COVID-19, the “anti-vaxxer” movement has laid the groundwork to undermine the critically important collective action to get vaccinated. In a very real way, this conspiracy theory stands to obstruct progress.

We have to fight the seductive comfort that conspiracy theories offer. But that means putting trust in some institutions that have rightfully lost some credibility in the eyes of the public: scientific institutions that are sometimes wrong or sometimes collude with big business, or media outlets that sometimes succumb to nationalism and put on blinders, and pharmaceutical companies on whom we rely to manufacture lifesaving medication and vaccines but who are obviously in it to make money and sometimes allow dangerous products on the market for that reason.

Getting past conspiracies is not easy to do, but it is imperative if we want to organize for a better world. There are many actual conspiracies out in the open that are well-documented and can be taken at face value—that the U.S. fights wars to further its financial and political interests, that fossil fuel corporations fund climate change denialism because it serves their purpose, or that pharmaceutical companies overcharge Americans for medication simply because they can. These real conspiracies may not be as sexy as the idea that shadowy figures have seeded a virus or that “9/11 was an inside job,” but they have a very real impact on our world that requires the unsexy work of political organizing on a mass scale. Pouring our energy and anger into the wrong direction ultimately hurts us, not the elites that conspiracy theorists claim to target.

This article was produced by Economy for All, a project of the Independent Media Institute.

Sonali Kolhatkar is the founder, host and executive producer of “Rising Up With Sonali,” a television and radio show that airs on Free Speech TV and Pacifica stations.