An interview with Moldovan novelist Iulian Ciocan

Moldova lies on cultural, linguistic, and geopolitical faultlines.

Until 1991 this eastern European country of around three million was part of the Soviet Union, where Russian was considered the language of prestige. Upon declaring independence, Moldova quickly reestablished strong cultural ties with Romania, its large neighbour to the West. Moldova was part of Romania between 1918 and 1940, and the two countries’ languages are entirely mutually intelligible — whatever speakers may call them.

Under Soviet rule, Moldovan was decreed a separate language from Romanian, and unlike Romanian was written with the Cyrillic alphabet. Today, both languages are written in the Latin alphabet. Many speakers in Moldova now consider this distinction artificial, and refer to their language as Romanian.

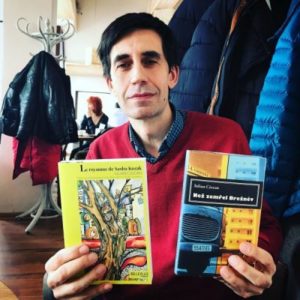

Iulian Ciocan holds translations of his novels in French and Czech. Chișinău, March 2018.

But Moldova’s divisions are also (geo)political: as the Soviet Union collapsed, the country’s eastern regions on the left bank of the River Dniester declared independence as Transnistria, where a predominantly Russian-speaking population looks at Moscow favourably.

Moldova’s turbulent history and myriad identities has fascinated its artists and writers, who have sought to make sense of their country’s self-perception and its place in the world.

One of them is Iulian Ciocan, a prominent journalist, literary critic, and author. Ciocan writes in Romanian and, like many Moldovans, speaks Russian fluently. He is one of the country’s most acclaimed writers and has gained international recognition; in 2011 he spoke about his work at the PEN World Voices festival in New York. Ciocan was born in the Moldovan capital of Chișinău in 1968. Much of his work, including novels such as ‘Before Brezhnev Died’ and ‘The Realm of Sasha Kozak’, attempts to make sense of Moldovans’ daily lives, hopes, and dreams during the Soviet period.

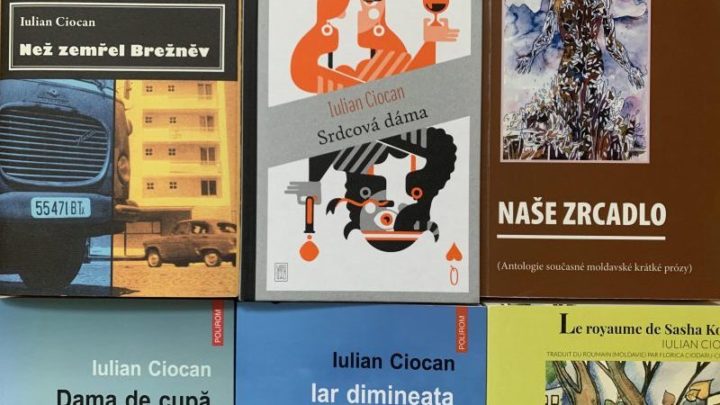

His latest work, ‘The Queen of Hearts’, concerns the absurd fate of a corrupt official working in Chișinău’s city hall — a fate which quite literally swallows him, and his country, whole. The gallows humour of Ciocan’s novels has won him accolades; his work has been translated into over seven languages, including English. In 2018, he won the Coup de Coeur prize at the Salon du Livre des Balkans.

I asked Ciocan about his work, sources of inspiration, and the state of literature in Moldova today. The interview has been edited for brevity.

Filip Noubel Today, you are one of the most renowned and widely translated Moldovan authors, but that was a long journey. What were the main challenges you met on the way?

Iulian Ciocan: The first and biggest problem is that the Republic of Moldova is almost unknown. I write in a language which, although beautiful, is not widely used internationally. I assume that in the West, Moldova is less known than [North] Macedonia, Kosovo or Albania, which has the famous writer Ismail Kadare. Once, a foreign magazine sent me a parcel, but it had trouble reaching me, because it had been sent to the Maldives. Hence there is a certain distrust from foreign publishers regarding the literati of this small and little known place. Can they really write something remarkable? Of course they can, because your location is not what matters the most.

Yet it is very difficult to convince them, to make them really look at your texts. When I started writing prose at the age of 38, I couldn’t even imagine having books published by foreign publishers. And even now I don’t have that many. My ninth novel will soon get published abroad, but, believe me, many Moldovan writers cannot even dream of such a thing. I have never had a good literary agent, so it’s not easy to interest foreign publishers. In stark contrast to this, all my translators are excellent and have often helped me to find my way to the publishers.

There are many problems, but if you keep complaining, you will not succeed. You have to write your stories, produce high quality texts. Then the problems will decrease.

FN: What is the state of literature and publishing in Moldova today? Does the state offer any sort of support?

IC: The situation isn’t very good. Reading [printed books] remains the privilege of a very small group of citizens: only around 12,000 people regularly buy books in Moldova, according to data circulated by publishers. Only two euros (US$2.20) are invested in books per capita per year, as opposed to 75 euros ($85) in Germany. The vast majority of writers write in Romanian and Russian, but I have the impression that the share of Moldovan writers on the Romanian market is higher than on the Russian market. As there aren’t many readers, private publishers often rely on children’s books or textbooks to get state grants.

FN: You share a language with Romania, as well as many cultural ties. Is this closeness an advantage or a challenge for Moldovan literature?

IC: Of course it’s a big advantage. In fact, Romanian-language literature from Moldova is part of Romanian literature. The simple fact that they can publish their books in publishing houses in Romania and appear on a larger market is a great opportunity for writers in Chișinău. Of course, competition is more serious in Romania, but if you have something to say, if you have value, you have nothing to lose. I’ll tell you a secret. I conceive my novels, even the dystopian ones, not only as a Bessarabian Romanian writer [Bessarabia is a historical region in eastern Europe encompassing Moldova and parts of Ukraine — ed.], but also as a writer who has experience of the Soviet past, as a man who lived on the Latin periphery of the Soviet empire. Thus there is no risk of being confused with Romanian writers.

FN: Moldova is not only known for its wine and textiles, but also for its mass emigration and endemic corruption. These issues feature prominently in your texts. Your latest novel, Dama de cupă (Queen of Hearts), starts with a description of corrupt schemes by state officials in Chișinău. What is the role of corruption in Moldova today? Is it changing?

IC: Corruption is, in my opinion, Moldova’s biggest vice. Cynics and politicians here are not tired of stealing or taking bribes. And my feeling is that nothing changes. The anaemic civil society is also to blame; there is no sense of belonging to a community. But I want to make it clear that corruption is only one dimension of this particular novel. The pit that gradually swallows Chișinău appears as a result of a tiny, insignificant sin, although the protagonist has much greater sins, including the fact that he is corrupt to the bone. ‘The Queen of Hearts’ is a novel in which I tried to say something essential about the world we live in today. It is a dystopian novel, but also a metaphysical and political adventure.