By Frances Madeson

Every day, says Donna Robinson, a bucket of bleachy water is delivered to a ward in Bedford Hills to be used by the sixty women housed there, her own daughter among them. That’s the extent of the supplies they receive to keep their area sanitized from COVID-19.

All but five of New York City’s 192 coronavirus deaths as of March 24 were of people aged forty-five and older, and the rapidly spreading infection rate in the city’s jails is a likely bellwether for how quickly COVID-19 could take hold in New York State prisons.

The women are in bunk beds with no functional ability to practice social distancing. When the virus comes their way, Robinson, an organizer for Release Aging People in Prison (RAPP), fears it’s going to spread quickly among inmates and guards alike.

“It’s batshit upside down crazy,” Robinson told hundreds of people during an online forum that RAPP conducted on March 25 to sound the alarm and organize to activate New York Governor Andrew Cuomo’s clemency powers to “let them go.”

“Here in western New York, when this scourge runs, they’re going to isolate them, put them in solitary,” Robinson said. “If there are deaths in droves, they’re going to have a Portable Mortality Unit; they’re not going to even send them to the hospital.” She added, “These are not garments to be thrown out. These are not garbage. They are human beings.”

According to testimony offered by RAPP to the state legislature in January 2019, there were at the time 10,239 older people in New York State prisons, making up 21 percent of the total prison population.” The group said the number of older people in New York prisons had increased four-fold—from 2,461 people to 10,239 people—over the last twenty-five years.

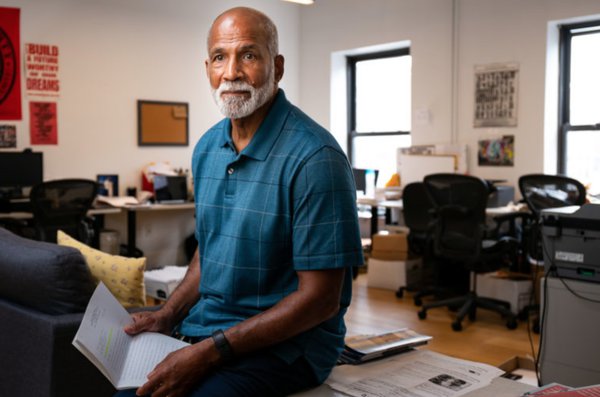

“They’re terrified,” RAPP Director Jose Hamza Saldana tells The Progressive about this class of highly vulnerable inmates. “They’re going through life in prison and this deadly disease is on its way. It’s coming. I imagine myself right there.” He says people who have not received a death sentence by any court of law should not receive one now due to bureaucratic inertia.

Saldana himself was incarcerated for thirty-eight years and denied parole four times. “For older people, with underlying conditions, all the health experts say that this virus is potentially fatal to you, and it’s a frightening, helpless position to really be in. And that should be shaking our conscience.”

All but five of New York City’s 192 coronavirus deaths as of March 24 were of people aged forty-five and older, and the rapidly spreading infection rate in the city’s jails is a likely bellwether for how quickly COVID-19 could take hold in New York State prisons.

As of March 26, according to New York City Mayor Bill DeBlasio, around 400 inmates in city lockups had already been released or were set for release. Neighboring New Jersey has already begun releasing the first thousand people from its jails, but so far Cuomo has not released any New York State inmates on compassionate release.

RAPP is calling for a much larger prisoner release as a humanitarian act to meet a humanitarian crisis. “We can move the dial on this by releasing as many people as possible, as quickly as possible,” Saldana says.

Carol Shapiro, a former parole board commissioner, advised the forum that the technology is already in place for remote parole interviews. “We should expedite,” she said.

A Jewish New Yorker, Shapiro expressed her fear that without action, New York State’s prisons and detention centers were “death camps” in the making.

“Even a good deed like mass clemency can never salvage this system; it has to go down,” he says. “This culture of punishment is a vampire we’ve got to put a stake to.”

“We should let them out right away and with very few conditions,” she said about those at risk. “We should not even be thinking about the offense. Let’s be honest, the majority of the people in our prisons do not need to be there. We need to change the conversation anyway!”

The coronavirus crisis presents an occasion to consider paradigm-altering ideas across many issue areas, including affordable housing, universal income, debt forgiveness, and Medicare for All—all progressive ideas that have been lying around waiting for an opportune moment.

Now is that moment, Saldana believes.

“Even a good deed like mass clemency can never salvage this system; it has to go down,” he says. “This culture of punishment is a vampire we’ve got to put a stake to.”

At the “Reimagining Justice” conference held in September 2019 by Vera Justice Institute, Daryl Atkinson, co-director of Forward Justice, fleshed out in a keynote the underdeveloped concept of “penal parsimony.”

Stopping short of abolition, the formerly incarcerated lawyer and policy advocate defined it as “the lightest liberty intrusion for legitimate societal purpose.”

In a 2014 report, “The High Costs of Low Risk: The Crisis of America’s Aging Prison Population,” the nonprofit Osborne Association laid out the economic cost of incarcerating older prisoners.

“The United States,” the report said, “currently spends over $16 billion annually on incarceration for individuals aged fifty and older—more than the entire Department of Energy budget or Department of Education funding for school improvements.”

In its most rudimentary application, penal parsimony would ask what legitimate societal purpose is served by the continued incarceration of elderly inmates who, according to Robinson, are so frail and doddering they “have difficulty walking from the bed to the toilet.”

Saldana eschews the word ‘rehabilitation’—“that’s their word,” he says—but he thinks American justice is capable of a major transformation.

“I don’t put [any] numbers on this,” Saldana explains. “What I mean by decarceration [is that] we’re gonna start with releasing the elderly, and just don’t stop.”

Frances Madeson has written about liberation struggles in the United States and abroad, and is the author of the comic novel Cooperative Village.