While concerns about climate change are increasing, the debate on the demographic issue has also got underway: can our planet feed 8 billion human beings? It is not easy to answer this question with a simple yes or no, depending on a great many interrelated factors and on the level of consumption that each of us considers necessary for oneself. And how much space do we wish or need to leave to non-human life forms on our planet?

In the meantime, we must clear up some misunderstandings: those who want to tackle the demographic issue do not want to produce a genocide or proceed to mass sterilization in Third World countries. Malthus himself, who gave his name to the often vituperated current of Neo-Malthusianism, being a good Anglican pastor, in 1800 preached chastity to limit population growth. Times have changed and the population has increased from one billion at the time to almost 8 billion today, eightfold in two centuries. Today we have many more elements – and we live in a world that has changed dramatically – to answer the question about the world’s population.

How can we measure whether a country has reached the level of overpopulation? When it is no longer able to meet the needs of its population and must resort to massive imports of food and energy from abroad and overseas. This is the case for the UK, which today produces only 52% of the food (and 64% of the energy) it consumes. The level of overpopulation also depends on many variables. Either the UK reduces the waste of food and resources and generally decreases its consumption, or it has to give birth to fewer children (better both), otherwise it will necessarily have to live at the expense of other countries and continents that will have fewer resources available for their own local populations.

Perhaps we should clarify that the expression “zero growth” referred to a population, generally perceived as negative, does not mean that no more children are born. In fact, it represents an optimal condition of stability, in which the number of births perfectly compensates for the number of deaths.

It is futile to ask “who is too much” or to point the finger at someone (whether it be Western consumer society or Third World peoples with a fast-growing populations). We need to cooperate on a global level to get out of the environmental crisis that afflicts our planet, involving all populations in a democratic process based absolutely on voluntariness and understanding, not on coercion.

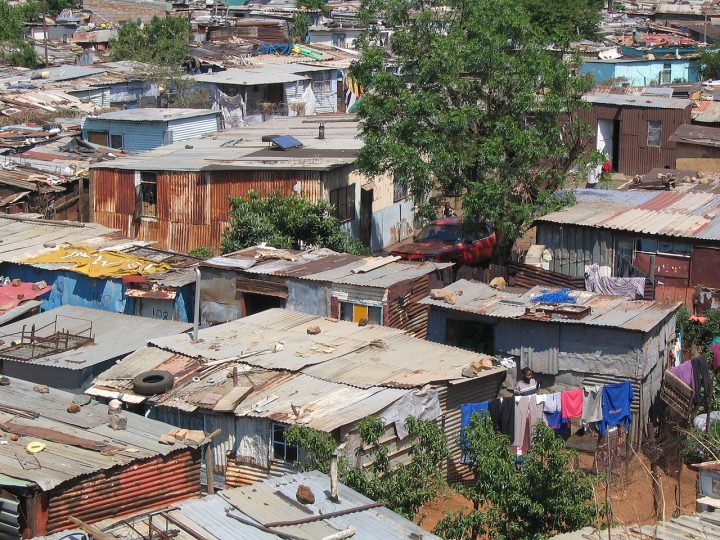

For Third World populations having children is often the only hope of having a chance of survival. In fact, the high infant mortality rate and the absence of pension systems that ensure a dignified old age for the elderly, combined with the lack of self-determination of women, lead to very high population growth rates in sub-Saharan Africa. Today, fast population growth takes place in highly urbanized environments in the shantytowns of the Third World. Bangladesh has a population density of 1,145 inhabitants per km2, more than 4 times that of the UK.

The capital of Nigeria Lagos will become by 2060 the largest city in the world, with nearly 60 million inhabitants (currently about 21 million). Rapidly tripling the population in an urban agglomeration does not create chances of survival, on the contrary it reduces them. How do we ensure the supply of drinking water and food to everyone, concentrated in one of the poorest and most deprived corners of the planet? This question concerns us, even if we live far away.

Finally, in examining the demographic issue, we must necessarily take into account the non-human world, that is, all forms of life and their right to exist: animals, plants and phenomena that we normally consider lifeless (inert), but that according to growing studies of the scientific world are not: the earth itself, clouds, water, even rocks. We, as a human species, cannot consider 100% of the planet as exploitable for our needs. The disappearance of forests, wetlands and wilderness areas (and the consequent mass extinction of many animals and plants), threatens in the long run the survival of our own human species.

The need to move from a capitalistic-competitive economic system to a decentralized and cooperative one is more urgent than ever. In this context, what measures should the human nation, of which we are all part, take in the demographic issue to face the great challenges of the future?

In Western countries

– Reduce the waste of food, natural resources and energy (degrowth) and enhance education in schools on these issues

– Move to less meat-based food (breeding has a very high environmental impact)

– Accept a gradual, slight decrease in the local population as a positive factor

– Welcome migrants as if they were our children, beyond ethnic, cultural and religious differences

– Stop land consumption that cements rural areas and protect forests

– Cooperate in international organisations to address the demographic issue together with poor countries

– Launch and continue intense campaigns to raise awareness, denounce and put pressure on the role of multinationals and economic, military and financial powers in determining inequality and poverty.

In the Third World

– Stop land grabbing, the expropriation of local populations and robbery of resources by multinationals and foreign countries

– Study ways to spread contraceptives through voluntary methods

– Elect democratic and non-corrupted governments that can implement welfare measures and greater self-determination for women

– Stop deforestation