Born 150 years ago, Gandhi’s perceptions about human sensibilities, social power and political truths began their transformation not in India, but South Africa.

Born 150 years ago this week, Mohandas K. Gandhi was a polarizing figure during his life and remains a lightning rod for controversy to this day. For example, in December 2018, a university in Ghana removed a statue of Gandhi because faculty and students claimed that he had shown contempt for black people while working in South Africa from 1893‒1914. The following month, as India memorialized Gandhi’s assassination in January 1948, a woman in India used a toy gun to squirt red liquid on a statue of Gandhi, whom she held responsible for India’s partition. Most recently, however, a group of people in South Africa carried placards proclaiming “Racist Gandhi must fall” while defacing a statue that depicted him as an attorney. They threw buckets of white paint on it, as well as on accompanying plaques that explained his history in the country.

Meanwhile, Hindu nationalists in India have erected statues to honor Gandhi’s assassin, Nathuram Vinayak Godse, who was a member of a Hindu nationalist group to which Prime Minister Narendra Modi and many of his political allies belong. Some Hindu supremacists now voice the view that Godse is India’s real hero while others remain incensed with Gandhi for having expressed sympathy for the country’s Muslim minority and blame him for Pakistan’s separation from India during partition.

Gandhi the person who arrived in South Africa would not be Gandhi the man who returned to India two decades later.

Gandhi is also often condemned by Dalits, who, because they are considered lower than the lowest caste by Hindus, have long suffered egregious persecution. The term “Dalit” means “broken men” in Marathi. These so-called untouchables now exceed 300 million and have increasing political sway, and many resent Gandhi’s rejection of a 1932 government proposal to create separate electorates, like distinct constituencies, for what the British called “depressed classes.” As Gandhi saw it, the measure would neither serve as penance by caste Hindus for having inflicted suffering on the Dalits, nor would it be a remedy for them.

So, what’s driving the attacks on Gandhi? Social scientists maintain that the present political environment in the Americas, Europe, South Asia and elsewhere has increased the disparagement (or worse) of the “other” along the lines of nationalism, religion, race, creed, gender and caste. Another possibility might be the current popularity of “purity tests,” which have been leading aggrieved groups to demand and expect what is, in essence, infallibility on the part of those perceived to be leaders or exemplars of a cause. Their perspective leaves no room for deviance, much less error — perceived or real.

Gandhi was attacked and criticized for his views and actions most of his life and to this day. The current allegations of racism are merely the most recent. Gandhi’s childhood under the British Raj, meaning rule by the British Crown, virtually guaranteed that he would be inadvertently conditioned toward bias regarding race. As an adult, he became in effect a British barrister and — while studying in Britain and later working in South Africa — appeared to internalize elements of the racism fortifying European colonialism.

When Gandhi moved to South Africa in 1893 to practice law, he found an Indian immigrant community inexperienced with political action and unable to unite cooperatively to fight the policies and laws demeaning and oppressing them. Being a brown newcomer himself meant that Gandhi too suffered the brunt of that country’s aggressive color bigotry.

Gandhi’s strategy for success — use more than one strategy

In the end, Gandhi the person who arrived in South Africa would not be Gandhi the man who returned to India two decades later. Few people, if any, would have been. What Gandhi saw and experienced there, and what he learned firsthand and through diligent reading, would contribute to alterations in his perceptions about human sensibilities, social power and political truths. It would also generate his formulation of methods and processes available for human beings of all backgrounds to take action nonviolently in the pursuit of fairness and justice.

Gandhi often showed flexibility regarding the outcomes that he sought, but was exceedingly precise regarding the actions to be used, for reasons of maintaining nonviolent discipline. Even today, the man and his contributions and failings continue to be misunderstood and sometimes misrepresented.

The prevailing acceptance of human rights and equality today is in part because of transformations set in motion by Gandhi. Though not always acknowledged, human rights laws and international conventions have often resulted because massive civil resistance campaigns fought for their recognition. Moreover, major civil rights, minority rights, women’s rights, and other evolving norms have been institutionalized as a result of movements utilizing insights gleaned from Gandhi’s experiments. His work on an inventory of problems in India altered people’s sense of right and wrong around the world. Gandhi not only exhorted individuals to refuse to cooperate with coercion, he maintained that social and political change can be produced through their own reasoning and cooperative action while giving them tools with which to bring about those alterations. Across the world today, the inheritors of Gandhi’s bequests are considerable in civil society groups and organizations.

Gandhi thwarts easy analysis partly because he often acted as if he were a social scientist, repeatedly gathering information and learning from trial and error. He had not set out to acquire a prominent role in life on Earth. In fact, he was painfully shy well into his early adulthood. Although targeted for racist attacks as a brown foreigner in South Africa, his commitment to experimentation with nonviolent action was continually evolving, in that he tested himself repeatedly.

Today’s standards cannot be used to judge someone or events from an utterly different period. Human beings evolve, and without appropriate interpretation, meaning is lost. To judge Gandhi as racist requires accepting what is called ahistoricism, meaning holding to the concerns of the present while ignoring the complexities and contexts of the past. Historical periods must be fathomed in their own terms.

Gandhi’s rough start in South Africa

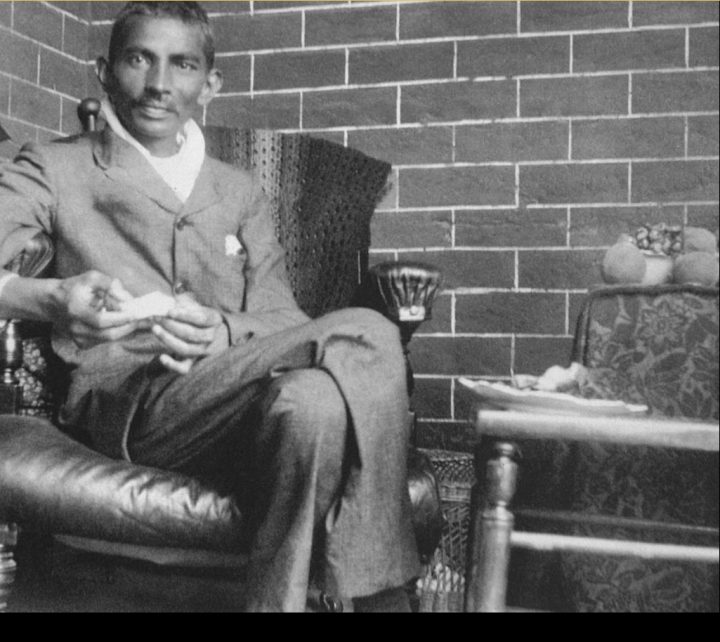

Gandhi codified the first comprehensive theory and praxis of nonviolent struggle through the work he began in South Africa and continued throughout his life. Aiming to follow in his father’s footsteps in what is now Gujarat and become a diwan, or chief executive officer, Gandhi had sought to obtain a foreign degree. Thus, at the age of 18 in 1888, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi sailed for Britain, where he would read at the Inner Temple in London for the law examination — despite being excruciatingly shy, indeed all but unable to speak publicly. During nearly three years in London, he absorbed sundry cultural attributes, perceptions, and attitudes, becoming for all intents and purposes a British barrister. While studying in London, Gandhi further internalized the racist conditioning that he had absorbed from the British colonialism of his early childhood rearing. Upon arrival in South Africa, he had not begun to fathom the lessons of diversity and inclusivity that would later animate his thinking.

Returning from London to India, Gandhi realized that being called to the bar in England did not mean success in Bombay. In 1894, he accepted a modest offer of 105 pounds sterling, first-class round-trip fare, and expenses to work on a commercial disagreement as counsel for Dada Abdulla and Company, a law firm in Natal, South Africa. Gandhi knew nothing of the colony’s “indentured” laborers imported from India three decades earlier to work in coffee, sugar and tea plantations. By 1890, some 40,000 mostly male Indians had been lured into semi-slavery through contracts binding them into service for a specified term. The dearth of opportunities at home, plus shortfalls of cheap labor in Natal, meant that more than half the migrant Indians remained in South Africa after their five-year contracts concluded.

By 1891, some 46,788 Indians were resident in the coastal colony of Natal, dominated by the British, with an African population estimated at 455,983. Only 10,729 men could then vote in Natal, all of them European apart from a handful. Another tier of Indian merchants, professionals, traders, and white-collar workers comprised 2,000 men, with 1,000 of that rank in the smaller inland colony of Transvaal, ruled by Afrikaners of Dutch descent who called themselves Boers. All the Indian settlers were contemptuously and without distinction dubbed “coolies” and forbidden to walk on footpaths or be out at night without permits.

Gandhi quickly discovered color discrimination in South Africa and confronted the realization that being Indian subjected him to it as well. He would not be an exception. At the Pietermaritzburg train station, railway employees ordered him out of the carriage despite his possessing a first-class ticket. Then on the stagecoach for the next leg of his journey, the coachman, who was white, boxed his ears. A Johannesburg hotel also barred him from lodging there.

Historian Maureen Swan portrays the typical working week of most Indian laborers who toiled on the sugar plantations as six nine-hour days. During crushing and planting seasons, however, these laborers faced 17- or 18-hour days, producing “abnormally high disease and death rates.” Indentured Indians also suffered privations and immigration restrictions and could not venture more than two miles beyond their place of work without written permission. Indians were commonly forbidden to own land in Natal, while ownership was more permissible for native-born peoples.

Gandhi found himself in a quagmire of animosity created by European administrators while simultaneously witnessing the defenselessness of Indian merchants and laborers of Hindu, Parsi, Muslim and Christian backgrounds — all of whom lacked parliamentary representation. The Boers and Britons, despite their differences, were tightly joined in perpetuating white monopolies of power and control.

In 1894, the Natal Bar Association tried to reject Gandhi on the basis of race. He was nearly lynched in 1897 upon returning from India while disembarking from a ship moored at Durban after he, his family, and 600 other Indians had been forcibly quarantined, allegedly due to medical fears that they carried plague germs. Local newspapers had reported an “Asiatic invasion,” stoking large numbers of hostile working-class Europeans to mobilize onshore, while the passengers awaited clearance for three weeks. Gandhi survived thanks to the quick thinking and artful use of a parasol by the police superintendent’s wife.

Although having arrived in South Africa to settle a legal dispute, Gandhi became a novice community organizer at the age of 34. His early efforts there on behalf of the Indian community generally involved incremental entreaties through letters, formal appeals and special delegations. In 1896, he published 10,000 copies of “The Grievances of the British Indians in South Africa,” the so-called “Green Pamphlet,” his first substantive publication, which he sent to newspaper editors throughout the country. In it, he addressed insulting and demoralizing practices faced by the Indians, mainly in Natal. With exceedingly limited experience, in 1903 he founded a weekly newspaper, Indian Opinion, with the goal of informing South African whites and Indians about each other, while also developing a framework to assist the Indians in addressing injustices.

By narrowing his focus to helping Indians in Natal and the Transvaal learn to restrain the colonial regime through political action, Gandhi tried to harness the broadest amount of sympathy while defying the government on specific, limited problems the Indians faced. These included the humiliating measures for registering immigrants and removal of oppressive restrictions on merchants.

Through the numerous activities undertaken on behalf of the Indian community, Gandhi slowly began developing into an unelected political figure in South Africa. His thinking was initially most compatible with that of Indian merchants, many of them from Gujarat and of his caste. His reformist approach remained far from anything remotely revolutionary. In Swan’s judgment, Gandhi cannot be considered a leader before 1906, nor for some time after that, because of his “timid strategy” and “unimaginative tactics.”

In the patois of the day, Gandhi considered the British Indians, along with African communities, as “colored.” Evocative of a perspective heard in the current political debates on the status of black and brown peoples in the United States, he understood that there existed scores of common hardships, but considered that every adversity could not be identically resolved. He wrote in 1906 in Indian Opinion, “[While] the Indian and non-Indian sections of the Coloured communities should, and do, remain apart, and have their separate organisations, there is no doubt that each can give strength to the other in urging their common rights.”

Gandhi did not seek to incorporate the indigenous African population into his campaigns in part because it was not bowed under the disabilities against which the Indians alone chafed, among them a three-pound sterling tax on Indian indentured laborers in Natal. Also, a century later, one cannot blithely assume that if he had approached the African indigenous peoples that they would have wholeheartedly welcomed an untested Indian trial lawyer to speak for them. Why would they?

Rare insight into Gandhi’s perspective at this time came to light decades later after his return to India, when on February 21, 1936, Gandhi invited a delegation of African American leaders to meet with him. Professor Howard Thurman, dean of Rankin Chapel at Howard University, Washington, D.C., questioned Gandhi about his South African experiences: “Did the South African Negro take any part in your movement?” Gandhi replied: “No, I purposely did not invite them. It would have endangered their cause.” The years required to persuade the Indians of the logic for why they should neither accept violence nor retaliate in kind may have made Gandhi cautious about asking comparable sacrifices from the African peoples.

Historian Ramachandra Guha observes that the types of indignities, discrimination, and restrictions of British and Boer imperialism burdening Indian immigrants would subsequently be applied more systematically to black Africans under the Afrikaners’ racially segregationist policy of apartheid, introduced in 1948. Such treatment of the Indians led Guha to assert, “The Indians should really be considered to be among apartheid’s first victims.” If that is the case, then Gandhi deserves credit for being among the earliest of apartheid’s adversaries.

With Africans comprising the overwhelming majority of Natal’s population, Gandhi developed meaningful social and professional relationships among an intergenerational community of black leaders. In 1900 in Inanda, John Langalibalele Dube, the founder of the South African Native National Congress, which became the African National Congress, or ANC, established the Ohlange High School, the first secondary educational institution for blacks in South Africa apart from missionary schools. It included a 300-acre communal settlement and training facility at Phoenix, where three years later Gandhi bought land and created his first ashram. Gandhi resided intermittently in this valley directly below Inanda, near Durban, until 1913. He and Dube sometimes met to discuss their (similar) philosophies of pursuing equality without violence in their respective communities. Each published a weekly newspaper to aid communications with the constituencies they assisted.

By 1914, Albert John Luthuli, a future chief of the Zulu people, was studying at Ohlange. Thirty-eight years later, Luthuli would be elected president-general of the ANC, in 1952. Although Gandhi was not directly involved in the ANC’s struggle, the influence of his thinking on it, including with Luthuli, is unmistakable. Luthuli’s adamantine insistence on the necessity for civil resistance as opposed to armed struggle was recognized worldwide when he became the first African awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, in 1960, recognizing him as “the leader of 10 million black Africans in their nonviolent campaign for civil rights in South Africa” and for advancing nonviolent action as “non-revolutionary, legitimate and humane.”

Internal and external conflict

During the Second Boer War — which took place between the British and the Boers in 1899-1902 — Gandhi held to his early convictions that because the Indians were in South Africa due to the British presence, they owed a certain allegiance to the Crown. He enlisted 1,100 Indian volunteers to serve as stretcher-bearers for an ambulance corps supporting British combat troops.

In 1906, a Zulu revolt erupted in British-dominated Natal after the government imposed a one-pound sterling tax on each male African. The Zulu are a branch of the Bantu ethnic group in southern Africa and the largest such ethnic grouping in South Africa, in what in 1994 became KwaZulu-Natal. Smaller in size than the Transvaal, Natal had 10 times the number of Asians. Zulu armed resistance began when Natal officials tried seizing the monies. Gandhi wrote, “A genuine sense of loyalty prevented me from even wishing ill to the Empire.” Hoping to make a favorable impression on government officials whose respect might facilitate his work on behalf of the Indians in Natal, Gandhi suggested yet another Indian ambulance corps. The British accepted the offer and assigned 24 Indians to serve as stretcher-bearers for nearly six weeks, nursing wounded Zulus.

“[M]y heart was with the Zulus,” Gandhi later wrote in his 1948 autobiography. “The wounded in our charge were not wounded in battle … [but] had been taken prisoners as suspects.” He wrote of the Zulus being flogged, causing “severe sores.” A medical officer told him, “The white people [are] not willing nurses for the wounded Zulus … [whose] wounds were festering.” Although Gandhi retained loyalties to the British for years, in little more than a decade his experiences would irrevocably alter his views on the British Empire.

After the war, from 1904 through 1906, Gandhi shared with his Indian Opinion readers the examples he had found in African and international news reports of how to overcome disunity and instill a shared sense of responsibility — in short, the prerequisites for political action. By 1905, Gandhi had differentiated a potent understanding while seeking ways to embolden the apprehensive Indians into overcoming their disagreements, telling them, “Even the most powerful cannot rule without the co-operation of the ruled.” He wanted them to understand that the ruling power must secure their cooperation and obedience, willing or coerced. In short, they were not powerless. They had a choice in the matter. This foundational comprehension of power would govern his experiments for the next 42 years and subsequently fuel the quest of contemporary nonviolent movements worldwide into the 21st century.

Gandhi came to envision both Indians and Africans as eventually winning freedom and enjoying the same rights as whites.

In August 1906, Gandhi learned that the Transvaal Legislative Assembly was considering the Draft Asiatic Law Amendment Ordinance, dubbed the Black Act, which would obligate every Indian man, woman and child from age eight to register their finger and thumb prints. Any Indian seeking work and lawful residence in the Transvaal would need to produce the registration certificate on demand. Gandhi viewed it as “abominable,” treating Indians like criminal offenders. Two concepts characterizing Gandhi’s work in South Africa were crucial to his approach to this ordinance and for his place in history: ahimsa — which is a core doctrine of Jainism forbidding injury to living beings — and satyagraha.

In brief, Gandhi interpreted ahimsa as a form of power whose essence is nonviolence, molding it into a tool of nonviolent action for effecting change in which, significantly, beliefs alone are insufficient. Distressed by the idiom “passive resistance” then used by English speakers to denote the absence of violence, and because the technique he was developing for social action was anything but compliant, in 1906 he turned to Sanskrit to define what would become the concept of satyagraha, a melding of satya, meaning Truth or justice, and agrahaconveying firmness, force or persuasion. For today’s reader, satyagraha can best be understood as a concept corresponding with nonviolent direct action or civil resistance. In 1907, he predicted that the time would come when “it may well be adopted by every oppressed people … as being a more reliable and more honourable instrument for securing the redress of wrongs than any which has heretofore been adopted.”

In October 1908, Gandhi would cross into the Transvaal without a certificate, an action of satyagraha against the ordinance, therefore courting arrest and jail time in a long complex struggle against the registration certificates. No longer primarily an organizer, he was maturing into a moral philosopher and political leader. For the satyagrahas in the Transvaal during 1907–10, some 3,000 Indians, including normally wary merchants, adopted his example by anticipating arrest, implying acceptance of jail. This was a remarkable development. By 1913, two decades after Gandhi’s arrival in South Africa, satyagraha would replace his initial conciliation-based sanctions of petitionary letters, appeals, delegations and court cases.

By 1908, the 39-year-old Gandhi had cultivated a view of all the so-called races as being within one human compass. Nothing had prepared him “for the intensity of racial prejudice in South Africa,” historian Guha judged, but he “decisively outgrew the racism of his youth.” Abandoning presumed disparities between the “civilized” and the “uncivilized,” Gandhi came to envision both Indians and Africans as eventually winning freedom and enjoying the same rights as whites. In much the same way that racism seeks “racial purity,” its lack of scientific substantiation was comparable with the theoretical degrees of purity from pollution upon which the social demarcations of the Hindu caste system had been built over thousands of years, so that by the early 20th century, more than 2,000 Hindu castes regulated the lines of interaction. Their speculative purity from pollution can no more be proved than assumptions of racial inferiority or superiority.

Gandhi had come to understand nonviolent resistance as a form of political struggle, not an assorted collection of personal beliefs and persuasions. His experiments in South Africa also led him to recognize the basic concept of the need to have women centrally involved in the nonviolent direct action of satyagraha. In 1912, Indian women migrants were compelled to action alongside men for the first time, opposing the governmental immigration legislation that would invalidate the legitimacy of non-Christian Indian marriages and nullify domicile rights for wives.

In what became known as the Natal Indian Strike, laborers left the collieries and plantations on foot so they would not be forced back to work, with women among those encouraging the strike. The campaign began with a small group of satyagrahis — four women, including Gandhi’s wife Kasturbai, and 10 men — who, at Gandhi’s behest, set out for the Transvaal. Their plan was to urge Indian mine workers to strike against the nullification law, and they were prepared to be arrested, given their lack of entry permits. Some of the party reached the miners without being arrested and persuaded them to join what historian Swan calls “a prolonged and widespread work stoppage,” by workers “only a few years removed from the pre-industrial Indian countryside” against the proposed injurious statute. On September 23, others pleaded guilty to having violated the immigrant acts and were sentenced to three months in prison. Kasturbai spent three months at hard labor.

Vowing not to accept the invalidation of their marriages, between 4,000 and 5,000 Indian laborers in northern Natal responded to the call within two weeks, when, Swan notes, 3,883 Indians worked the mines. As the campaign endured, white South Africans became sympathetic to the Indians’ plight and added their demands for the government to amend its discriminatory policies. What became an eight-year satyagraha culminated when Gandhi was released from prison in June 1913 to negotiate with Field Marshall J. C. Smuts, representing the government, which produced results for their campaign.

Admittedly, the circumstances faced by migrant Indians in South Africa would worsen after Gandhi’s departure in July 1914. Yet the impact of his presence would be significantly felt there again some 40 years later, with historian Guha crediting the South African campaigns against apartheid as being “directly inspired by Gandhi.” Indeed, “the first major mass movement against apartheid, the Defiance Campaign of 1952, would use methods pioneered by Gandhi, with African and Indian protesters defying racial laws by entering offices, train compartments and other public spaces designated for ‘Europeans only.’” Even now, Gandhi’s experiences in South Africa remain cornerstones for the uncompleted efforts by South Africans to resolve their enduring struggles over race and class.

By the time Gandhi left to return to India, he was a far different man than he was upon arrival in South Africa 20 years earlier. As his relationships with native black South Africans grew stronger, he was able in time to transcend the racism he had absorbed from the British — a fact that modern-day critics often fail to acknowledge. He also arrived back in his homeland possessing a nonviolent technique for achieving justice, which he believed was ethical, practical and effective, and would go on to reshape dramatically our world for the better over the next century.