By Roberto Savio

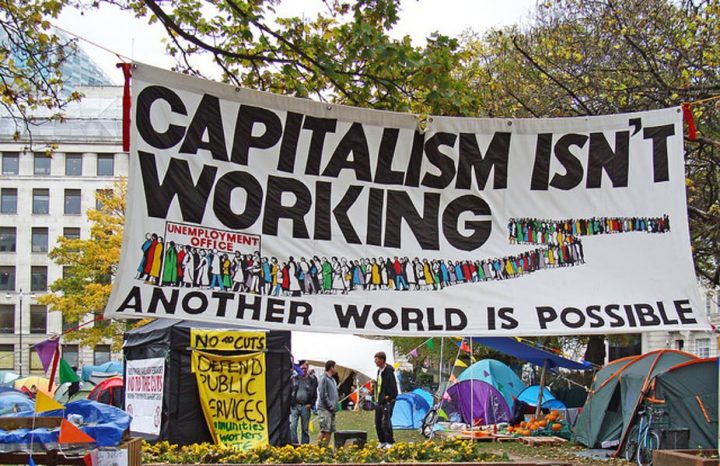

The first World Social Forum in 2001 ushered in the new century with a bold affirmation: “Another world is possible.”

Roberto Savio

That gathering in Porto Alegre, Brazil, stood as an alternative and a challenge to the World Economic Forum, held at the same time an ocean away in the snowy Alps of Davos, Switzerland.

A venue for power elites to set the course of world development, the WEF was then, and remains now, the symbol for global finance, unchecked capitalism, and the control of politics by multinational corporations.

The WSF, by contrast, was created as an arena for the grassroots to gain a voice. The idea emerged from a 1999 visit to Paris by two Brazilian activists, Oded Grajew, who was working on corporate social responsibility, and Chico Whitaker, the executive secretary of the Commission of Justice and Peace, an initiative of the Brazilian Catholic Church.

Incensed by the ubiquitous, uncritical news coverage of Davos, they met with Bernard Cassen, editor of Le Monde Diplomatique, who encouraged them to organize a counter-Davos in the Global South. With support from the government of Rio Grande do Sul, a committee of eight Brazilian organizations launched the first WSF.

The expectation was that about 3,000 people attend (the same as Davos), but instead 20,000 activists from around the world came to Porto Alegre to organize and share their visions for six days.

WSF annual meetings enjoyed great success, invariably drawing close to 100,000 participants (even as high as 150,000 in 2005). Eventually, the meetings moved out of Latin America, first to Mumbai in 2004, where 20,000 Dalits participated, then to Caracas, Nairobi, Dakar, Tunis, and Montreal.

Along the way, two other streams—Regional Social Forums and Thematic Social Forums—were created to complement the annual central gathering, and local Forums were held in many countries. Cumulatively, the WSF has brought together millions of people willing to pay their travel and lodging costs to share their experiences and collective dreams for a better world.

WSF’s Charter of Principles, drafted by the organizing committee of the first Forum and adopted at the event itself, reflected these dreams.

The Charter presents a vision of deeply interconnected civil society groups collaborating to create new alternatives to neoliberal capitalism rooted in “human rights, the practices of real democracy, participatory democracy, peaceful relations, in equality and solidarity, among people, ethnicities, genders and peoples.”

Yet, the “how” of realizing any vision was hamstrung from the start. The Charter’s first principle describes the WSF as an “open meeting place,” which, as interpreted by the Brazilian founders, precluded it from taking stances on pressing world crises.

This resistance to collective political action relegated the WSF to a self-referential place of debate, rather than a body capable of taking real action in the international arena.

It didn’t have to be this way. Indeed, the 2002 European Social Forum called for mass protest against the looming US invasion of Iraq, and the subsequent 2003 Forum played a major role in organizing the day of action the following month with 15 million protesters in the streets of 800 cities on all continents—the largest demonstration in history at the time.

However, the WSF’s core organizers, who were not interested in this path, held sway, a phenomenon inextricable from the democratic deficit that has always dogged the Forum.

Indeed, the WSF has never had a democratically elected leadership. After the first gathering, the Brazilian host committee convened a meeting in Sao Paolo to discuss how best to carry the WSF forward.

They invited numerous international organizations, and on the second day of the meeting appointed us all as the International Council. Several important organizations, not interested in this meeting, were left off the council, and those who did attend were predominately from Europe and the Americas.

In the ensuing years, efforts to change the composition created as many problems as they solved. Many organizations wanted to be represented on the Council, but due to vague criteria for evaluating their representativeness and strength, the Council soon became a long list of names (most inactive), with the roster of participants changing with every Council meeting.

Despite repeated requests from participating organizations, the Brazilian founders have refused to revisit the Charter, defending it as an immutable text rather than a document of a particular historical moment.

AT A CROSSROADS

The future of the WSF remains uncertain. Out of a misguided fear of division, the Brazilian founders have thwarted efforts to allow the WSF to issue political declarations, establish spokespeople, and reevaluate the principle of horizontality, which eschews representative decision-making structures, as the basis for governance.

Perhaps most significantly, they have resisted calls to transcend the WSF’s original mission as a venue for discussion and become a space for organizing. With WSF spokespeople forbidden, the media stopped coming, since they had no interlocutors. Even broad declarations that would not cause schism, like condemnation of wars or appeals for climate action, have been prohibited.

As a result, the WSF has become akin to a personal growth retreat where participants come away with renewed individual strength, but without any impact on the world.

Because of its inability to adapt, and thereby act, the WSF has lost an opportunity to influence how the public understands the crises the world faces, a vacuum that has been filled by the resurgent right-wing. In 2001, globalization’s critics emerged mainly on the left, pointing out how market-driven globalization runs roughshod over workers and the environment.

Since then, as the WSF has floundered and social democratic parties have bought into the governing neoliberal consensus, the right has managed to capitalize on the broad and growing hostility to globalization, rooted especially in the feeling of being left behind experienced by working-class people.

Prior to the US financial crisis of 2008 and the European sovereign bond crisis of 2009, the National Front in France was the only established right-wing party in the West. Since then, with a decade of economic chaos and brutal austerity, right-wing parties have blossomed everywhere.

The unsettling rise of the anti-globalization right has scrambled many political assumptions and alliances. At the start of the WSF, our enemies were the international financial institutions, such as the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. Now, these institutions support reducing income inequality and increasing public investment.

The World Trade Organization, the infamous target of massive protests in 1999, was our enemy as well, for skewing the rules of global trade toward multinational corporations; now, US president Donald Trump is trying to dismantle it for having any rules at all.

We criticized the European Commission for its free market commitment, and lack of social action: now we have to defend the idea of a United Europe against nationalism, xenophobia, and populism. These forces have upended and transformed global political dynamics. Those fighting globalization and multilateralism, using our diagnosis, are now the right-wing forces.

LOOKING AHEAD

Is there, then, a future for the World Social Forum? Logistically, the outlook is not good. Rightwing Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro, an ally of authoritarian strongmen around the world, has announced that he will forbid any support for the Forum, putting its future at grave risk.

Holding a forum of such size requires significant financial support, and a government at least willing to grant visas to participants from across the globe. The vibrant Brazilian civil society groups of 2001 are now struggling for survival.

Indeed, right-wing governments around the world attack global civil society as a competitor or an enemy. In Italy, Interior Minister Matteo Salvini has been pushing to eliminate the tax status of nonprofits. Like Salvini in Italy, Trump in the US, Viktor Orban in Hungary, Narendra Modi in India, and Shinzo Abe in Japan, among others, are unwilling to hear the voice of civil society.

Their escalating assault on civil society might spell the formal end of the World Social Forum, although the WSF’s refusal to evolve with the times left the organization vulnerable to such assaults.

If the World Social Forum does fade away as an actor on the global stage, we can take many valuable lessons from its history as we mount new initiatives for a “movement of movements.” First, we need to support civil society unity. Boaventura de Sousa Santos, the Portuguese anthropologist and a leading participant in the WSF, stresses the importance of “translation” between movement streams.

Women’s organizations focus on patriarchy, indigenous organizations on colonial exploitation, human rights organizations on justice, and environmental organizations on sustainability. Building mutual understanding, trust, and a basis for collective work requires a process of translation and interpretation of different priorities, embedding them in a holistic framework.

Any initiative to build transnational movement coordination must address this challenge. While it is easier to build a mass action against a common enemy, nurturing a common movement culture requires a process of sustained dialogue.

The WSF was instrumental in creating awareness of the need for a holistic approach to fight, under the same rubric, climate change, unchecked finance, social injustice, and ecological degradation. Building on that experience with how the issues intersect is critical to a viable global movement.

The WSF has made possible alliances among the social movements, which got their legitimacy by fighting the system, and the myriad NGOs, which got theirs from the agenda of the United Nations. This is certainly a significant historical contribution, enabling the next phase in the evolution of global civil society. Second, we need to balance movement horizontalism and organizational structure.

For the vast majority of participants in cutting-edge progressive movements over the past half-century, the notion of a political party, or any such organization, has been linked to oppressive power, corruption, and lack of legitimacy. This suspicion of organization, reflected in the core ideology of the WSF, has contributed to its lack of action.

This tendency to reject verticality out of fear of its association with oppression poses a major challenge to the formation of a global movement: those who would be, in principle, its largest constituency will question overarching organizational structures.

Based on historical experience, they fear the generation of unhealthy structures of power, the corruption of ideals, and the lack of real participation.

Nevertheless, coordination is essential for a diverse global movement to develop sufficient coherence. The task is to find legitimate forms of collective organization that balance the tension between the commitments to both unity and pluralism.

Third, a global movement effort must navigate a new media landscape. The Internet has changed the character of political participation. Space has shrunk, and time has become fluid and compressed. Social media has become more important than conventional media.

Indeed, it was essential, for example, to the election of Bolsonaro in Brazil and Salvini in Italy, as well as Brexit in the UK. US newspapers have a daily run of 62 million copies (ten million from quality papers like the Wall Street Journal, New York Times, and Washington Post), while Trump tweets to as many followers.

\Contemporary communications technology, while used to sow confusion and abuse by the right, must be central to transnational mobilization campaigns fostering awareness and solidarity.

Political apathy among potential allies remains as great a challenge as the right-wing surge. This is not a new phenomenon.

The triumphant pronouncements of the end of ideology and history three decades ago helped mute explicit debate on the long-term vision for society. Instead, the technocrats of the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and the US Treasury foisted the Washington Consensus on the rest of the world: financial deregulation, trade liberalization, privatization, and fiscal austerity.

The benefits of globalization would lift all boats; curb nonproductive social costs; privatize health and more; and globalize trade, finance, and industry. Center-left parties across the West resigned themselves to this brave new world.

“Third Way” leaders like British Prime Minister Tony Blair argued that since corporate globalization was inevitable, progressives could, at best, give it a human face. In the absence of a real alternative to the dominant paradigm, the left lost its constituency. The wreckage left behind by neoliberal governments has become the engine for the populist and xenophobic forces from across the globe.

Looking ahead, to build a viable political formation for a Great Transition, we must find a banner under which people can rally. Climate action has increasingly served this function, with the youthfulness of the climate movement a reason for hope. The climate strike movement, led by Swedish student Greta Thunberg, has engaged tens of thousands of students worldwide and shown that the fight for a better world is on.

These new young activists, many of whom have probably never heard of the WSF, do not pretend to come with a pre-made platform; they simply ask the system to listen to scientists. The lack of a full vision allows them to avoid many of the WSF’s problems, yet still underscore how the system has exhausted its viability in the face of spiraling crises.

Millions of people across the globe are engaged at the grassroots level, hundreds of times more than related to the WSF. The great challenge is to connect with those working to change the present dire trends, making clear that we are not part of the same elite structures and, indeed, share the same enemy.

The historic preconditions undergird the possibility of such a project, our visions of another world give it a direction, and the growing restlessness of countless ordinary people is a hopeful harbinger.

Can we find the modes of communication and alliance to galvanize the global movement and propel it forward? I do not see much value in a coalition of organizations and militants who meet merely to discuss among themselves.

Collective action is necessary for counterbalancing the decline of democracy, increasing civic participation, and keeping values and visions at the forefront. In the WSF, the debate about moving in this direction has been going for quite some time, but has repeatedly run up against the intransigence of the founders.

It would be a mistake to lose the WSF’s impressive history and convening authority. But we need to recreate it in order to reflect the present barbarized. Will we be able to reform WSF, and if this is not possible, create an alternative?

Citizens have become more aware of the need for change than they were when we first met in Porto Alegre many years ago. But they are also more divided, some taking the reactionary path of following authoritarian leaders, some the progressive path of social justice, participation, transparency, and cooperation.

As the conventional system destabilizes and loses legitimacy, giving life to a revamped WSF—or creating a new platform—might be easier than the challenge of launching the process eighteen years ago.

Still, realizing the next phase will take new leaders, wide participation, and recognition of the need for new structures. In these times, this is a tall order.

———————

*Roberto Savio, Publisher of Other News, Italian-Argentine Roberto Savio is an economist, journalist, communication expert, political commentator, activist for social and climate justice and advocate of an anti neoliberal global governance. Director for international relations of the European Center for Peace and Development.

He is co-founder of Inter Press Service (IPS) news agency and its President Emeritus.