São Paulo – the largest city in the Americas – was recently plunged into darkness in the middle of the day due to smoke from the Amazon rainforest burning more than 2,700km (1,700 miles) away.

These fires have brought global attention to the forests of South America, but the crisis surrounding them has deep roots. To understand what is happening in the Amazon today, it’s necessary to understand how deeply exploitation of the forest, and the Indigenous peoples who live within it, are ingrained in the global economy.

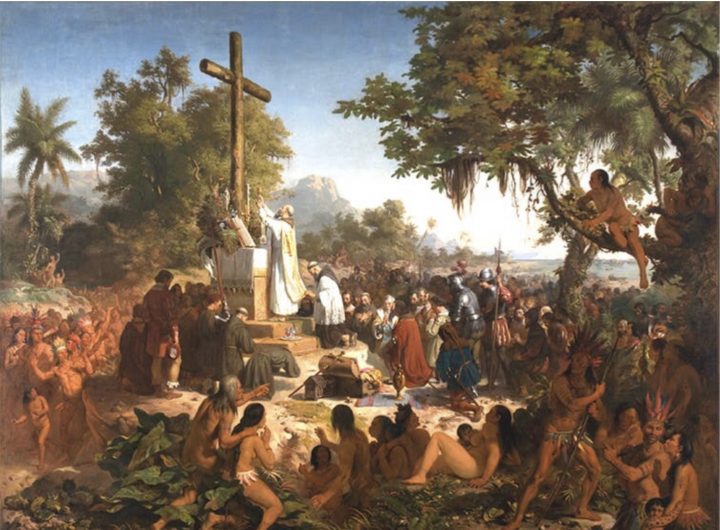

The first Portuguese explorers arrived in Brazil on April 22 1500. The region didn’t at first appear to offer the gold or silver that was to make Central America a tempting target for colonisers, but it did present a more obvious asset: vast forests with a seemingly inexhaustible supply of timber.

Read more:

Amazon in flames: Brazil’s Huni Kuin indigenous people count the social costs of fire and conflict

The region’s Brasilwood trees produced a valuable red dye, and with the colour red in fashion in the French court, Brazil’s forests quickly became a target for profit-minded Europeans. Brasilwood was so prevalent before colonisation that it lent its name to the country. But after centuries of overharvesting, these trees are now a highly endangered species.

Indigenous peoples were initially incentivised to help harvest timber in exchange for European goods. But eventually the native peoples were enslaved and made to destroy the forests which had provided the wood for their homes and the game and plants for their diet.

Once cleared of trees, land was turned into plantations to grow labour-hungry cash crops such as sugar, encouraging the enslavement of yet more Indigenous people. When they proved too few in number, vast numbers of people were taken from Africa and forced into slavery alongside them.

Global economy, local cost

The Mata Atlântica, a vast tropical forest which stretched down the east coast of the country and well into its interior, was an obvious target for the seafaring colonisers, who needed to ensure the materials they harvested could be easily transported to overseas markets.

But the environmental cost of this process was massive. As much as 92% of the Mata Atlântica has been destroyed over the past 500 years, erasing the places in which hundreds of distinct cultures evolved over the preceding millennia. Vast numbers of species disappeared along with it.

Walter Hardenberg/Wikipedia, public domain

In the 19th century, the British cleared yet more forest to establish rubber plantations. Despite officially being keen to encourage the abolition of slavery, the British-owned Peruvian Amazon Company violently forced Indigenous people into servitude. The anthropologist Wade Davis would later comment that

The horrendous atrocities that were unleashed on the Indian people of the Amazon during the height of the rubber boom were like nothing that had been seen since the first days of the Spanish Conquest.

The American industrialist Henry Ford founded a rubber-producing town deep in the Amazon rainforest in 1928. He hoped to “develop that wonderful and fertile land” to produce the rubber his company needed for car tires, valves and gaskets. Fordlândia, as it became known, was abandoned in 1934.

Ruins of Fordlândia, circa 2005. Méduse • CC BY-SA 3.0 Wikipedia

By the middle of the 20th century, the size of the Indigenous population first encountered by the Portuguese had shrunk by 80-90%. Meanwhile, the global demand for beef accelerated the destruction of South American forests to free up new grazing land.

Global brands, such as McDonalds, have been linked with Brazilian beef, half of which is produced on lands which were once rainforest. Just as demand for sugar and rubber fuelled historic slavery, the global appetite for beef drives deforestation and displaces Indigenous people today.

New frontiers

The current crisis in the Amazon began with illegal gold miners, loggers, and farmers setting fires to clear lands for new enterprises. This process has been promoted and celebrated by the government of Jair Bolsonaro and the country’s powerful agribusiness sector. Already dislocated people face an increasingly grave situation. This is especially true for uncontacted groups who’ve yet to cultivate biological resistance to the diseases which outsiders can introduce, or develop the cultural experience necessary to navigate today’s complex political landscape.

Many of Brazil’s Indigenous cultures are completely oriented around their forests. In the modern era, their belief systems endure in groups such as the Kaingang, a part of the Gê peoples who occupied the southern parts of the Amazon rainforest and lived throughout the Mata Atlântica. They must actively nurture and protect these beliefs in the face of tremendous outside pressure.

Unlike in the US, dense forests and unmapped locations, not to mention uncontacted peoples, ensure continuity between the earliest days of European colonisation and modern Brazil.

Darren Reid, Senior Lecturer, American History and Popular Culture, Coventry University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.