Subsidies for onshore wind power were cut by the UK government in 2015. Then the main reasons given were that it was too expensive and that the public didn’t support it. Amber Rudd MP, then head of what was the Department of Energy and Climate Change, said in a statement to parliament: “We are reaching the limits of what is affordable and what the public is prepared to accept.”

Fast-forward to 2019: onshore wind is the UK’s cheapest form of electricity, and our newly-published academic research shows that public support for renewables is high and getting steadily higher. Support for nuclear and fracking on the other hand is low and decreasing.

These trends are demonstrated by the government’s own data: the UK Energy and Climate Change Public Attitudes Tracker (PAT). The PAT has been running quarterly since 2012, meaning there is a huge amount of data to show how attitudes have changed over the past seven years. In total, more than 50,000 people have been surveyed, making it the largest and most representative dataset of its kind.

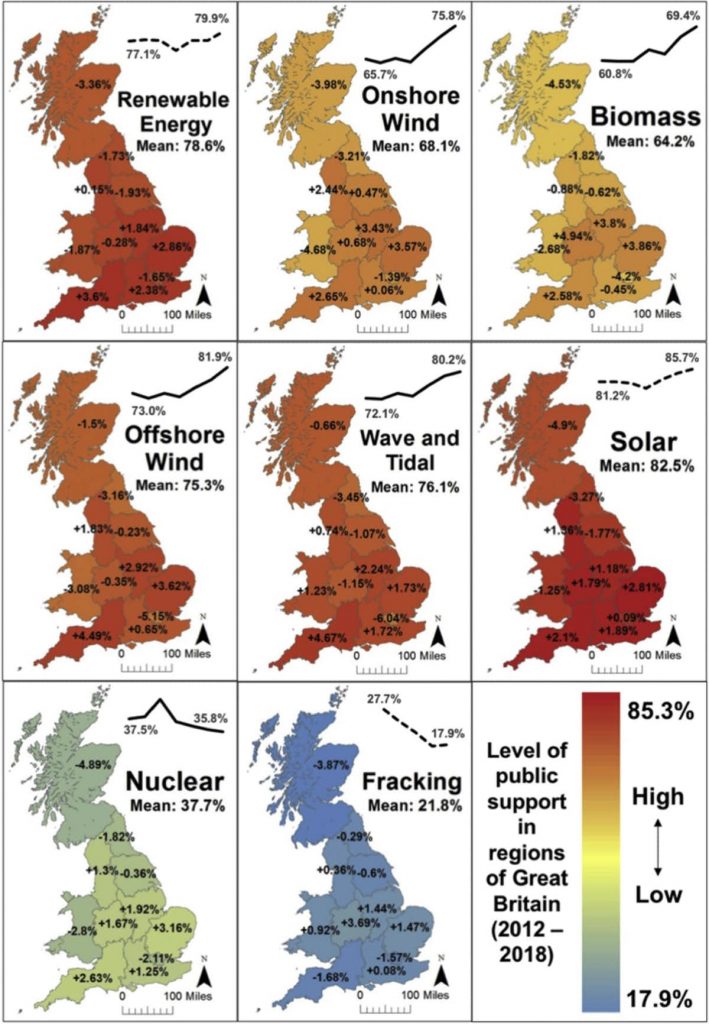

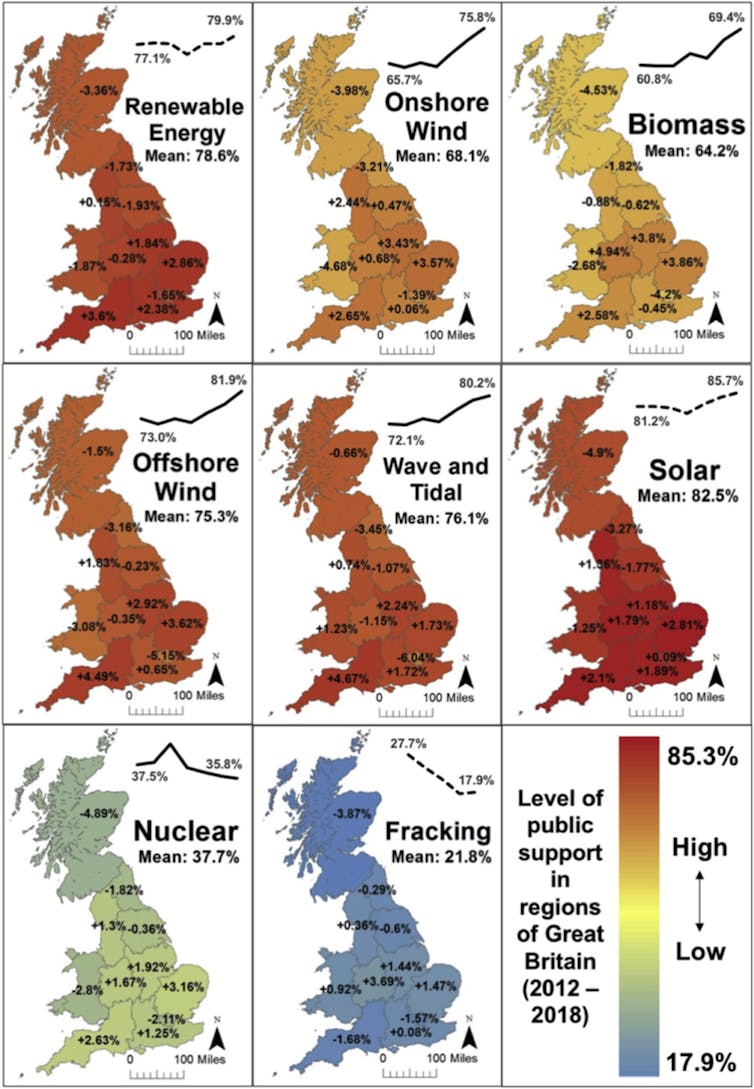

Along with colleagues at the University of Leeds, I analysed the PAT dataset to dig a bit deeper into what it can tell us. As well as looking at how trends in public support have changed over time, we also explored whether trends varied geographically. While the map below shows there is some variation, the overall trends are pretty consistent across Great Britain. (Unfortunately there isn’t enough data for Northern Ireland to ensure confidentiality).

Roddis et al, Author provided

So, are energy policymakers listening to the public? The short answer is: no. At present, the UK government is pursuing the energy technologies which receive the lowest levels of public support (nuclear and fracking), while cuts to various subsidy schemes are making it more difficult for popular onshore renewables such as wind and solar to get built.

One exception is offshore wind – the third most popular technology – which was recently given fresh backing by the government. The survey does not ask about support for fossil fuels such as coal or natural gas, so it’s not possible to directly compare people’s preferences with existing fossil-based energy infrastructure.

However, our study does show that concern for climate change was a particularly important predictor of attitudes. People who worried more about the climate were more supportive of renewables, and people who were less concerned were more supportive of nuclear and fracking. As concern over the climate crisis continues to grow (a trend also shown by the PAT), it seems likely that renewables will continue to enjoy high public support, while support for nuclear and fracking (as well as other types of fossil fuel) will continue to fall. This is a positive sign for the transition to a low carbon society.

Our results also suggest that some sections of the public may be having a stronger effect on energy policy than others. We found that young people and women were more likely to support renewables, while older people, men and higher social classes were more likely to support nuclear and fracking. It is perhaps not a coincidence that this demographic group has the most similar views to the status quo energy policy, given the lack of diversity in the energy sector. This highlights the need to get more women and people of all social backgrounds into the top energy jobs, so that decisions are more representative of society and its preferences.

The UK government recently put into law the bold ambition to reach net zero carbon emissions by 2050 – the first major economy in the world to do so. This is a fantastic step in the right direction and sets the bar for other countries around the world. But (and there’s always a but), this is only possible if technologies pursued are genuinely low carbon, cost effective (as renewables increasingly are) and have the backing of the public.

Given the introduction of this new net-zero target, it is time for policymakers to rethink the direction of the UK’s energy future, and to listen more carefully to what the public really wants. With average support of 82.5%, solar energy is more popular by far than certain other recent political decisions in the country. As we hear so often from politicians these days, the people have spoken.

Pip Roddis, PhD Researcher, Public Attitudes Towards Energy, University of Leeds

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.