History suggests that attempts to exclude such regional powers produce instability, or worse.

The web of American sanctions on Iran is being tightened. The White House recently cancelled the waivers that still permitted a few countries to import Iranian oil and announced new sanctions on Iran’s metallurgist industry. The exchange rate of the Iranian rial is in freefall while both inflation and unemployment grow rapidly. Meanwhile, aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln arrived in the Persian Gulf and tensions are rising by the day. The European Union, France, Germany, United Kingdom – and the Netherlands – are largely watching the spectacle of unapologetic American realpolitik. However, these countries also remain party to the roughly four-year-old nuclear deal with Iran in which they committed to supporting Tehran economically in exchange for temporary limitations on its nuclear development.

Now that war threatens, a strategic reorientation has become urgent. The issue is less about Iran and more about the importance of stability in the Middle East after years of revolutions and conflict. Europe, after all, is not separated from the Middle East by the Atlantic Ocean. If the Syrian civil war offered a preview of the refugees, terrorists and criminals that conflict can generate, the specter of war with Iran should induce great caution.

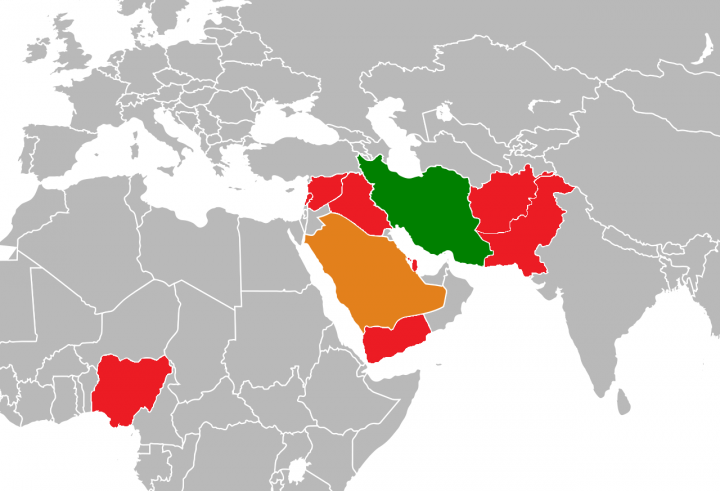

And why would such a conflict be warranted in the first place? Because the US seeks regime change in a country with which it developed a traumatic obsession since the Iranian revolution of 1979? Because Saudi-Arabia – the country that orchestrated the murder of Jamal Kashoggi – fears Iran as rival, or because Israel remains in conflict with Hezbollah due to its continued repression of the Palestinians? Iran is a regional power with a solid place in the political order of the Middle East. History suggests that attempts to exclude such regional powers produce instability, or worse.

Obviously, the foreign policy record of Iran is not without blemish. On the positive side of the ledger one can list full compliance with the terms of the nuclear deal, a key role in combatting the Islamic State and the interdiction of substantial volumes of drugs in transit from Afghanistan to Europe. On the negative side of the ledger one can include Iranian support for the bloody regime of President Assad in Syria, its linkage with armed groups in Lebanon and Iraq that hinder the development of these countries and the occasional liquidation of political dissidents on European soil.

But the problem with this kind of inventories is that they quickly lead to paralysis. And that aptly describes European and Dutch political behavior at the moment while international tensions are on the rise. Brussels, Berlin, London and Paris remain hesitant to support Iran economically to face unilateral US sanctions despite their solemn promises of the nuclear agreement. Ignoring these sanctions is difficult, but not impossible. The EU’s INSTEX-mechanism enables bilateral trade with Iran without recourse to the dollar or US-linked elements of the global financial system. Bypassing US sanctions does not just require technical ingenuity however, it also demands political courage and capital. After all, the full force of the White House’s ire is likely to be unleashed on ‘sanction busters’, however legally permissible and defensible their actions may be. Because European and American markets are deeply and lucratively connected, direct bilateral confrontation with the US is not attractive.

But it is possible to break the European impasse to advantage by supporting Iran via a concrete cooperation initiative with China. If the EU and China cooperate to ignore US sanctions, it raises the cost of confrontation for the White House. It might re-enable the possibility of having a normal conversation about the role of Iran in the region. Additional advantages of such an approach include the creation of a broader front against the generally aggressive policies of the Trump-administration and, in time, increasing the ability to conduct an autonomous European foreign policy. To enable such a strategic innovation, a few ingredients are required:

First of all, Iran would need to make serious concessions to render such an approach viable from an EU and Chinese perspective. For example, by publicly confessing regret for liquidations on European soil, by sending the Syrian president Assad to the UN’s negotiating table in Geneva with a serious proposal and/or by agreeing to place the armed groups in Iraq that are linked to Iran under greater practical supervision of the Iraqi government. An informal agreement on preferential tariffs for Chinese import of Iranian oil for the next decade will probably also help. Second of all, China and the EU must put a confidence building measure in place that also generates mutually beneficial profit. This could take the form of a joint consultative and governance structure for investment initiatives in the Middle East that build on the European ´Connectivity´ and the Chinese ´Belt & Road´ strategies, buoyed by joint capital injection into the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. Third of all, it requires a structural dialogue with moderate representatives of the Iranian government such as Mr. Mohammad Zarif of Foreign Affairs, Dr. Ali Rezaei of the Expediency Council and Mr. Najafi Khosroui of the parliamentary committee for foreign affairs.

The Dutch government can play a role in shaping such an approach as an extension of its recently adopted strategic note on relations with China. Or by assisting Brussels in contributing to a structural dialogue with Iran. It will definitely not be an easy ride, but every passing day makes the effort more necessary.