Monday May 27 was a public holiday in the UK, the fourth such “bank holiday” in the past six weeks. On each of these days, people made fewer commutes, they left their computers and machines switched off, and the country generally used less energy.

In fact, my rough calculations below indicate that, depending on the season, each bank holiday could save more than 100,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide emissions.

So let’s conduct a thought experiment in which hypothetically Britain switches overnight to a four-day work week. Would that actually lead to less energy consumption, and fewer emissions?

The idea of a four-day week keeps popping up, for various reasons. For instance, an experiment conducted in New Zealand last year showed it boosted productivity levels. But I want to look at the idea of reducing the working week as a tool to fight climate change.

Back in 2006, two economists found that simply changing American working hours to European levels would lower US emissions by at least 7%. The following year, the US state of Utah conducted a test: it switched state employees to a four-day (albeit still 40-hour) work week and found that this led to significant energy savings, mostly because of less need for air conditioning, as well as lower emissions as a result of reduced traffic.

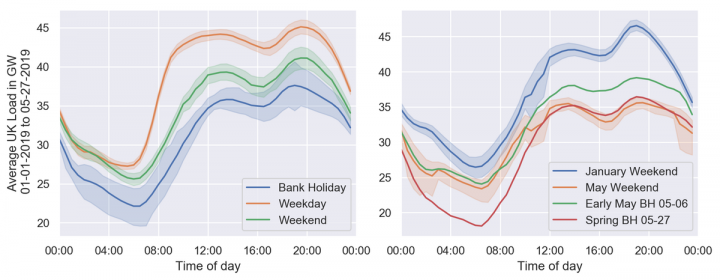

In order to estimate energy savings, first we must look at how much is consumed, commonly called the “load”. In the below graph, I have plotted the UK’s total electricity demand on a typical weekday, weekend day and bank holiday, as it changes throughout the day. I used data for every day in 2019 until yesterday (Jan 1 – May 27). This is called a load curve:

Denes Csala / ENTSOE, Author provided

Throughout the day, total electricity load fluctuates between 20 and 45 gigawatts and the nine to five workday pattern shows up very clearly. Demand is at its absolute peak just before 8pm but the curve has a typical double peak shape, with another one around midday. At the weekends, people tend to get up a couple of hours later, but the maximum energy consumption is still in the early evening – however, overall consumption is lower by 10%.

On the four bank holidays so far in 2019, consumption dropped, on average, by a further 9%. But the variance on these days – that is the “spread” of the data – is much larger. We must therefore look into the seasonal variations.

The winter months are colder and darker, so there will usually be more demand for heat and light in January than in May. It therefore makes more sense to compare the two May bank holidays with days in the same month.

ChrisO at English Wikipedia • CC-BY-SA-3.0

However, this year’s early May bank holiday was actually 6% above the average May weekend day in terms of consumption, while the late May bank holiday was around 6% below average. Therefore – based on this very limited sample – one could reasonably argue that these extra days off could be counted as regular weekend days.

In terms of consumption, a four-day working week would then effectively mean a three-day weekend, and electricity consumption falls on weekends by around 10% (this is not far off Utah’s estimate, after adjusting for the difference in actual working hours).

Some gigawatts are cleaner than others

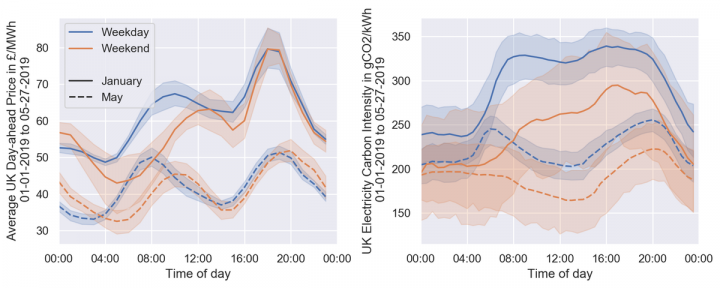

But to estimate the true emissions savings, we must look at the sources of energy production. Coal and natural gas power are obviously very different from wind or solar, and the availability and cost of the various energy sources changes throughout the day.

UK electricity is most expensive (left) and carbon-intensive (right) in the evening peak hours.

Denes Csala / ENTSOE, Author provided

The rule of thumb here is that at higher overall levels of electricity demand, more of that electricity will be generated from fossil fuels. That is because the EU mandates that cleaner energy sources be used first. While this rule might change in the near future, for now it means that lower electricity demand will mean lower emissions per unit generated. In fact, so far this year, British electricity was on average 17.5% less carbon intensive on weekends than weekdays.

All this means that if the UK was to introduce a four-day week, effectively replacing a work day with an extra weekend day, it would potentially reduce energy consumption for that day by 10% and emissions intensity by 17.5%. These two effects add up: the lower electricity consumption of the weekend combines with lower carbon intensity, as there is less need to switch on polluting coal or gas plants, therefore potentially lowering emissions on any given day by 22% in May or 25% in January.

In sheer numbers, this would mean saving 82,000 tonnes of CO₂ in May or 146,000 in January. As there are seven days in a week, lowering emissions for one of those days by, on average, 23%, would lead to an overall emissions saving of 3.3%. That’s 110,000 tonnes of CO₂ per week – equivalent to removing 1.2m cars from the road. And as this looks at electricity not petrol, it does not even count the carbon savings from the reduced traffic jams…

Dénes Csala, Lecturer in Energy Storage Systems Dynamics, Lancaster University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.