By Dr Hakim*

Dear friends,

“Salam (peace)!” is how Afghans greet one another, some of them simultaneously placing a hand over their hearts.

But, while everyone including Afghans wants peace, the Afghan Peace Volunteers and I have observed that the human species appears to be stuck on violent peace. We think that this is because most of us are reared as armed doves, like the one drawn by Wifred Hildonen for Cartoon Stock below.

Using Wilfred’s cartoon analogy, the Afghan Peace Volunteers and I are differentiating violent peace from nonviolent peace based on whether a society includes or excludes the use of weapons and armies as a resort to secure peace.

To date, the earth has housed violent peace. Human beings are the armed doves inhabiting the planet under the threat of lethal weapons, including 14,575 nuclear warheads. Even small island-countries like Singapore are spending more and more money to acquire superior weaponry from the military industrial complex.

We’re not differentiating between violent and nonviolent peace to judge anyone, as we would only be judging ourselves. We’ve tried nothing but violent peace in Afghanistan, to everyone’s loss. The time is overdue to pursue peace without weapons or armies, so that we can all enjoy the kind of peace we human beings dream about.

So, please trust your humanity, and trust that we share that humanity too. Like you, we wish to protect and defend our loved ones, so we don’t make this call on the people of the world lightly: “Don’t just pause. Stop! Consider nonviolent peace. It won’t harm you. It is the love we’ve always wanted!”

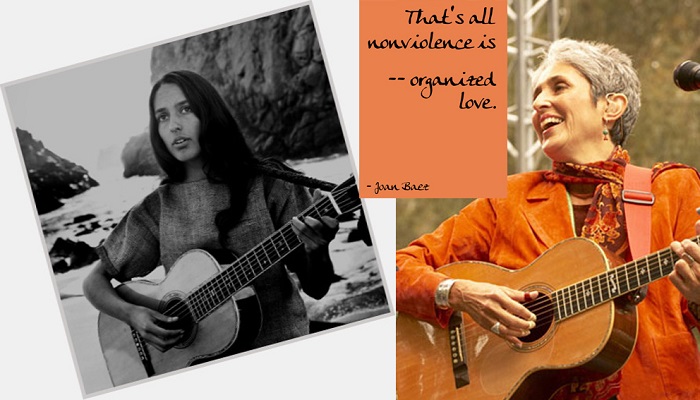

We so badly want societies that are highly organized on the foundation of love. This is already happening in many places through the local establishment of egalitarian, nonviolent practices. Joan Baez said, “That’s all nonviolence is – organized love”.

It is happening among the Afghan Peace Volunteers, like with Afghan 11th grade student Rashid, whose story I had begun telling in a previous post.

Rashid’s father was killed in a suicide bombing attack on a mosque in Kabul, for which a Pakistani militant group, Lashkar-e-Jhangvi, claimed responsibility. Rashi’s father was selling oranges at the mosque. Rashid was so devastated by this loss that he became inconsolably depressed and couldn’t bring himself to attend school for three months.

Once during a counselling session, I was listening to Rashid describe the tightness and pain he feels in his chest when he remembers the prison-like religious school he was forcefully enrolled into. Rashid recalled the incessant punishments in class, and the loneliness….The tears started pouring down his cheeks, not the sort of tears that sought any attention, but flowy, tender tears.

“Do you think you can heal yourself of the war inside you?” I asked Rashid recently.

“Yes, by changing the way I think. I can ask questions, and look for evidence before I believe any claim about war or other matters,” he replied.

I asked what he would say if his mother asked to take revenge, against the Pakistani “terrorists”, or against the Afghan extremists who, through traumatic indoctrination at the religious school, tried to brainwash him into joining them to wage the “holy war”.

“I will tell her: If I take revenge, you know that they will retaliate with even fiercer vengeance. You could be hurt. I could lose everything,” Rashid said.

I probed deeper, as my own personal journey towards understanding war and peace involved a freeing up of my basic assumptions, “After all that your mother has gone through, don’t you think that it’s her right to fight back?”

“Teacher,” Rashid explained to me, “There is an Afghan saying, “Blood cannot wash away blood.” Taking revenge doesn’t work.”

“But, Rashid, how will you be able to allay your mother’s fears, or even your own fears, if there were no military forces to defend you and your mom? Who will protect you?”

“My father was killed even when the Afghan army and the US/NATO forces were here defending us in Kabul. What we need is a people’s defense, in which the people bring security by conversing with the groups in conflict. We shouldn’t use weapons, because if we do, others will also use weapons against us. Look at the current peace negotiations in Afghanistan. While they negotiate, the sides in conflict are increasing their fighting and killing! How is peace ever going to come?” Rashid explained.

Rashid was stating what even the US Joint Chief of Staff, Marine Corps General Joe Dunford and the United Nations Secretary General Antonio Guterres had both said on different occasions, “There is no military solution in Afghanistan.”

“I used to admire those who looked strong holding dangerous weapons like this or like that…,” Rashid said, switching his arm posture as if he was holding a gun. “I used to think that Afghanistan must have an army to defend the country. I was a fan of the army generals.”

In most countries of the world today, saying something like this will get serious censure, “Rashid is unpatriotic. He is a traitor, maybe a Talib!” As armed doves, we consider the military almost sacred.

“Now, though I respect army generals and even militants as human beings, I don’t like what they do. I used to think that fighting proves how courageous I am. I was like a smart phone that was programmed by a system run by the government,” Rashid said.

I was reminded that I was speaking to a young person who belongs to the digital age and smart phone generation. It’s youth like Rashid and Swedish climate activist Greta Thurnberg who are rising up to change our obsolete and unresponsive systems. Greta had said, “We can’t save the world by playing by the rules because the rules have to change.”

I could see Rashid applying his mind, the way he does in school, getting first position in his 10th grade class last year, “after the classmate who paid bribes for his grades left school”.

“Is it possible to re-program the human smart phone?” I asked, though I’ve been thinking that with the repetitive war negotiations among fully armed players in the Afghan conflict, neither adult human beings nor our communication systems are very smart.

“Of course, once we understand the systems that did the programming, we can un-install the program, or format it!” Rashid quipped.

Rashid thinks we can reprogram ourselves for nonviolent peace

Rashid is becoming the other dove that is within him, the nonviolent dove who offers an olive branch, without any weapon strapped under his wing.

Baa mihr ( With love ) !

Hakim

*Dr Hakim, ( Dr. Teck Young, Wee ) is a medical doctor from Singapore who has done humanitarian and social enterprise work in Afghanistan for more than 10 years, including being a mentor to the Afghan Peace Volunteers, an inter-ethnic group of young Afghans dedicated to building non-violent alternatives to war. He is the 2012 recipient of the International Pfeffer Peace Prize and the 2017 recipient of the Singapore Medical Association Merit Award for contributions in social service to communities.