Emily Lindsay Brown, The Conversation; Gemma Ware, The Conversation, and Khalil A. Cassimally, The Conversation

There has been a torrent of media coverage about violent crime among children and young people in the UK. But it seems to offer little consensus on what’s causing this crisis, what the impact of measures taken by government and police are and what should be done to curb the violence.

In a debate often dominated by politicians, celebrities and media commentators, the voices of academics who have spent years researching this issue have not been heard enough.

That’s why we’re bringing you a round up of evidence-based views on the knife crime epidemic – including what action is really needed to prevent more young lives being lost.

Many of the academics featured have worked directly with young people and communities affected by knife crime, or with authorities and organisations working to manage it.

The epidemic in numbers

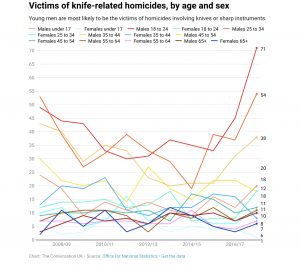

- How many? 285 knife-related homicides recorded in the year ending March 2018 – the highest number since the Home Office Homicide Index began more than 70 years ago.

- Who is affected? Young men aged 18 to 24 are the most affected. But there’s also been a 77% increase in homicides committed with knives by under-18s (2016 to 2018). And a 93% increase in the number of under-16s admitted to hospital due to knife attacks (since 2012).

- The rate at which men are currently being killed by violence is over double that for women. And while statistics don’t detail the social backgrounds of victims and perpetrators, research indicates there’s a greater chance of being killed by violence the poorer you are.

Read more:

Homicide rates are up in young men – austerity and inequality may be to blame

Why is knife crime increasing?

Discussions of violent crime among young people often start and finish with policing. But for academics, investigations begin with the experiences of young people themselves, as they seek to discover the underlying causes of knife crime.

1. Toxic environments for children, created by austerity

Knife crime is a symptom of the toxic environments that adults create around children, who then become both perpetrators and victims. It is created by politicians and by the politics of austerity. Stephen Case, professor of criminology, Loughborough University, and Kevin Haines, professor, University of Trinidad and Tobago

- Homes, schools, neighbourhoods or recreational activities can become toxic environments for children, when their relationships and experiences fail to nurture them, protect them and help them to achieve their potential.

- These toxic environments can leave children disaffected, fearful and vengeful. They are scared and provoked into carrying knives, joining gangs and committing violent acts.

- It is no coincidence that the vast majority of knife crime takes place in neighbourhoods suffering from huge social disadvantage and disinvestment.

Impact of austerity in numbers

£422.3m: reduction in spending on services for young people in last six years

3,500: number of youth service jobs lost (since 2010)

600: number of youth centres closed (since 2010)

130,000: number of places in youth centres eliminated (since 2010)

2. Children and young people are afraid of becoming victims

Carrying a knife often started as a way to avoid becoming a victim … Most of the people I spoke to who had carried a knife had been threatened, some on multiple occasions. Some had been attacked and a few had been severely injured. Peter Traynor, senior research assistant, Manchester Metropolitan University.

Traynor’s research documented how some young people started carrying knives to avoid being victimised. He also points out that some had gone to the authorities for help, but had largely been ignored.

The one time I went to the police … when I was stabbed … they walked into the house and said how many people done it? I said so and so many people done it from that gang … and they all kind of looked at each other – as if it’s gang affiliated or whatever isn’t it? So they didn’t really care. But if it was just a normal person … they’d have taken it a lot more serious – 17-year-old boy from London.

3. Children and young people don’t trust the authorities to protect them

The link between carrying a weapon and distrusting the police is an important new finding … It’s possible that young people who live in high-crime neighbourhoods or who are already involved in crime may not see the police as being able or willing to protect them from harm. In those situations, it is unsurprising that a young person would see carrying a weapon as justified or necessary. Iain Brennan, research psychologist, University of Hull.

If people feel society is unfair, they are less inclined to play by the rules and more likely to lash out violently. James Densley, associate professor, University of Oxford, and Michelle Lyttle Storrod, PhD researcher, Rutgers University.

- Many neighbourhoods with high crime are already inclined to distrust police, owing to their experiences of abuse and institutional racism.

- As violence has risen, the proportion of offences for which police have identified the culprit has fallen, and this further erodes civilians’ trust in authority.

- When police fail to solve or deter crime, people will bypass law enforcement and use violence to resolve disputes or protect themselves from danger.

- Growing tensions between police and communities can lead to further criminality, because successful police work depends heavily on cooperation with the public.

- Shortage of police investigators has been described as a “national crisis” – even London’s Metropolitan Police Service is short some 700 detectives.

According to Becky Clarke, a criminal justice researcher, and colleagues at Manchester Metropolitan University, reintroducing ineffective and discriminatory policing can lead to greater distrust and even cause more young people to carry weapons. Not only are the policing strategies being proposed right now likely to be ineffective, they say, but the strategies will certainly increase the criminalisation of young people and potentially increase weapon carrying.

Gangs, drill music, social media – overstated impact?

Gangs and youth violence are regularly conflated in mainstream media reports and government policy. Yet data from the Metropolitan Police in London has shown that a gang element was identified in only “a relatively small amount of serious youth violence” – under 5% of cases (2011 to 2016)

Drill music has come in for heavy criticism by Metropolitan Police Chief Cressida Dick, who in 2018 called on platforms such as YouTube to remove content which “glamourises” violent crime. It’s only the latest in a long series of panic about music videos. Fifteen years ago, for instance, ministers were concerned about “rap lyrics”. The panic about drill music “is leading to the criminalisation of everyday pursuits”, says academic Joy White, University of Roehampton. She warns that young people from poor backgrounds are now becoming categorised as troublemakers through the mere act of making a music video.

Social media may play some role in normalising the carrying of weapons, as documented by research carried out by James Treadwell, professor in criminology at Staffordshire University. But academics stress that the role of social media has been overstated, or at very least oversimplified by the media and policy makers.

How can the problem be solved?

Just giving police more power is not the solution – academic consensus

So far, government plans to tackle the issue have focused on granting police greater powers to surveil, stop and search, and punish “suspicious” young people.

As part of the UK government’s decision to enhance police powers, Sajid Javid, the home secretary, will seek to introduce Knife Crime Prevention Orders which:

- Can apply to any person aged 12 or over who carries a knife, has been convicted of a knife-related offence, or is suspected by police of carrying one.

- Can impose curfews, geographical boundaries or social media restrictions.

- Can result in conviction and a prison sentence of up to two years if the order is breached.

Javid’s proposals are flawed, because they are based on the fundamental misunderstanding that you can prevent violence by identifying and punishing those identified as ‘at risk’ of offending. But stigmatising young people as ‘risky’ draws them into conflict with the authorities, as young people become over-policed and over-surveilled. Jo Deakin, criminologist, and Laura Bui, criminologist, both at University of Manchester.

London’s gang matrix

London’s Metropolitan Police has a database that lists individuals as “gang nominals” with each given an automated violence ranking of green, amber or red.

It came under scrutiny by human rights group Amnesty International last year. According to Amnesty’s report, it could affect the lives of 3,806 people, 80% of whom are between 12 and 24 years old.

The gang matrix appears to discriminate against ethnic minorities: 78% of the people listed on the the matrix are black, despite the fact that black people only make up 27% of those people known by police to be responsible for serious youth violence – and only 13% of London’s population is black.

Ssoosay/Flickr., CC BY-ND

Solutions need to put children and young people first

Academics consistently advocate solutions that put children and young people first.

Here are some solutions for the UK government that academics have proposed:

- Stop stigmatising young people – listen to them instead

- Divert children and young people away from toxic environments and into positive, nurturing ones that meet their basic needs

- Invest in youth services, social care and extracurricular activities

- Provide educational support to reduce school exclusions and improve outcomes

- Work with families and communities to support, educate and rehabilitate young people

- Invest in community-based policing to restore trusting relations

- Create opportunities for training and employment to improve young people’s chances finding work and building professional relationships

More relevant articles written by academics

Knife crime is a health risk for young people – it can’t be solved by policing alone

How former offenders can make great mentors for at-risk teens

An expert (and father) comments

Thanks to James Treadwell, Anthony Ellis, Stephen Case, Kevin Haines, Laura Kelly, Ellie Munro, Becky Clarke, Patrick Williams, James Densley, Michelle Lyttle Storrod, Robert Ralphs, Iain Brennan, Joy White, Jo Deakin, Laura Bui, Daragh Murray, Pete Fussey and other academics who have written for The Conversation.![]()

Emily Lindsay Brown, Editor for Cities and Young People, The Conversation; Gemma Ware, Society Editor, The Conversation, and Khalil A. Cassimally, Community Project Manager (Audience development), The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.