Sheila M. Cannon, Trinity College Dublin for The Conversation

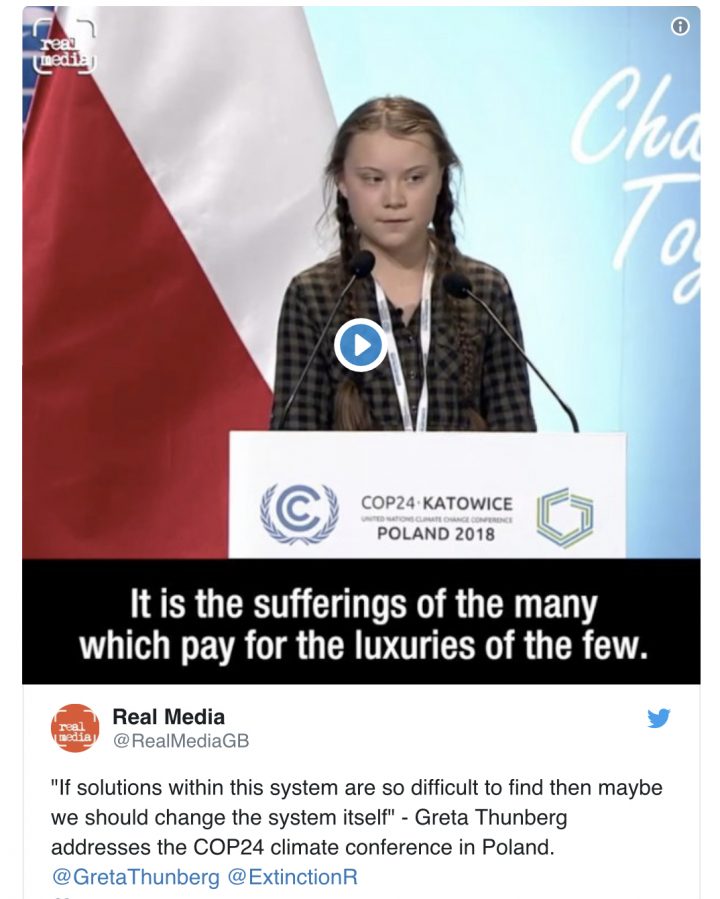

Greta Thunberg, the 16-year-old Swedish climate activist, is calling for system change. At a press conference in Brussels, she told the European Commission that in order to fight climate change we need to change our political and economic systems – a message that has been repeated on signs and in chants in the student climate strikes around the world.

The school climate strikes, which she started alone in August 2018, have become a social movement with 1,659 strikes planned for March 15 in 105 countries.

But what is system change? How do entire systems change? When we see “save the planet” initiatives, they often look like individual decisions that don’t cost much, like switching to a bamboo toothbrush or washing containers before you recycle them. By all means, do these things, but don’t confuse them with system change.

Most people don’t know how to change political, economic and social systems. They end up making token gestures instead that may even perpetuate the problem. There’s also the question of how to overcome powerful vested interests that benefit from the current system. But there is research that can help us understand system change.

Neo-institutional theory is one approach to understanding how and why people organise collectively. People create meaning, follow rules and reproduce structures – such as classrooms, businesses, offices and community halls – based on assumptions of what is right and proper. Classrooms look similar, not because each time we set one up we rationally decide how to do so, but because we make assumptions about what a classroom is supposed to look like.

Because we are part of these meaning structures, we reproduce existing norms and beliefs and resist change. System change happens when we don’t take our assumptions for granted, which allows more and more people to question the status quo.

Scanning the horizon

Thunberg is telling us that our current political and economic systems are no longer fit for purpose. She is pointing out that the emperor has no clothes.

Changing a system takes time. My research on the LGBT movement in Ireland documented efforts and achievements over 40 years. Homosexuality went from being a crime, to being celebrated in a progressive movement. While the referendum on marriage equality took one day in 2015, the efforts of many to change the system took decades.

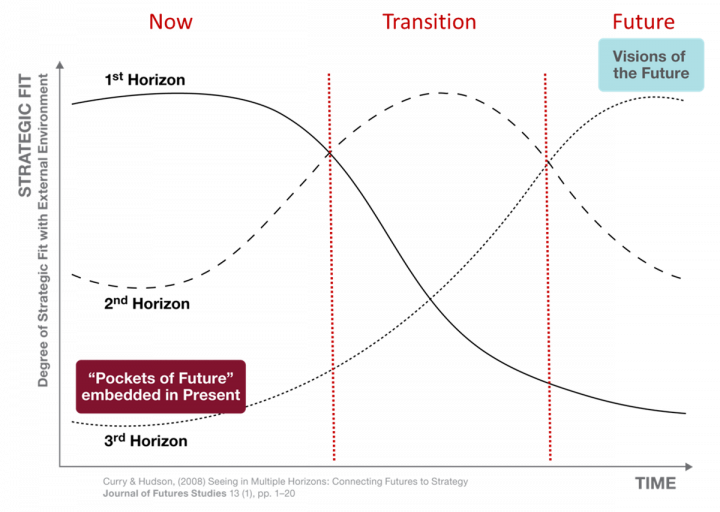

The Three Horizons Framework can help explain the different factors that lead to changing systems. Horizon one is business as usual – the status quo – and the outgoing institution in times of change. Horizon three is the new institution – with newly legitimised structures and beliefs. The space between them is horizon two, which is occupied by people focused on social change – who lead the transition from an old system to the new.

Sheila Cannon, Author provided

Most people recognise the problems with the present system and want to help society move to something more sustainable. Products like bamboo toothbrushes exist to monetise that concern, but because they’re sold in plastic and shipped around the world, their production and distribution still consumes fossil fuel and does nothing to change the existing economic or political system that is fuelling climate change. A collective challenge to political and economic elites is likely to be more effective in forcing this transition.

When aspects of horizon three appear – glimpses of a more sustainable system – they are usually rejected as illegitimate or too radical. When Rosa Parks sat down at the front of the bus in a move to promote civil rights in America in 1955, she was condemned. Looking back after system change has happened, these people are seen as leaders.

The end of capitalism?

The system that needs to be changed to avert climate disaster is capitalism, which is losing its legitimacy largely due to the system’s failure to respond effectively to climate change.

Applying all I’ve learned about how systems change, it’s possible to imagine that the current system which sustains business-as-usual capitalism – horizon one in the framework – is occupied by those who continue to produce, sell and consume products and services that rely on fossil fuels. That’s most of us, but horizon one is also maintained by climate deniers and investors in fossil energy, who, despite the scientific evidence, keep chugging along.

A more sustainable system could include policies we might currently consider “extreme”, like universal basic income. This is a guaranteed payment for all people regardless of their wealth which could help break the cycle of production and consumption that pollutes the atmosphere and fills the ocean with discarded plastic. Evidence suggests there is growing support for this, particularly among young people.

Extending human rights to non-humans and even to ecosystems is another idea that seems radical today but is gaining traction and could define an alternative system in future. One thing is for sure, we’ll look back in horror one day at how humans treated the natural world, as many already do in the present.

If the climate strikers can continue to grow their movement and sustain momentum, their leadership could be an important part of society’s transition to a more sustainable system in horizon three.

Capitalism may seem permanent, but research shows that systems inevitably change over time, and are ultimately created and reinforced by us. But in order to change anything, people must question their own role in the system first.

Sheila M. Cannon, Assistant Professor of Social Entrepreneurship, Trinity College Dublin

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.