Bobby Duffy, King’s College London for The Conversation

Immigration led the headlines again over the holiday season. Around 100 migrants were found on beaches or rescued from boats in the English Channel, sparking talk of a “crisis” and “major incident” and leading the home secretary, Sajid Javid, to cut short his Christmas break to chair a meeting with senior officials at the Border Agency and National Crime Agency.

It’s yet another example of how coverage of migration in the media and political rhetoric run way ahead of the reality, and fuel misperceptions about the scale, nature and impact of the issue.

This has real consequences, not just for how people feel about migration, but for nationally vital issues like Brexit, given that just about all analyses put concern about immigration at or near the top of the reasons why a majority of UK voters supported leaving the EU.

Misperceptions about migration are so commonplace they’re often accepted with a shrug. But they shouldn’t be – they should make us determined to do better in countering them and making a positive and, more importantly, truthful case for immigration.

I’ve been studying misperceptions for 15 years, and immigration is one of the areas that people in the UK are most wrong on, in many different respects.

We get a lot wrong

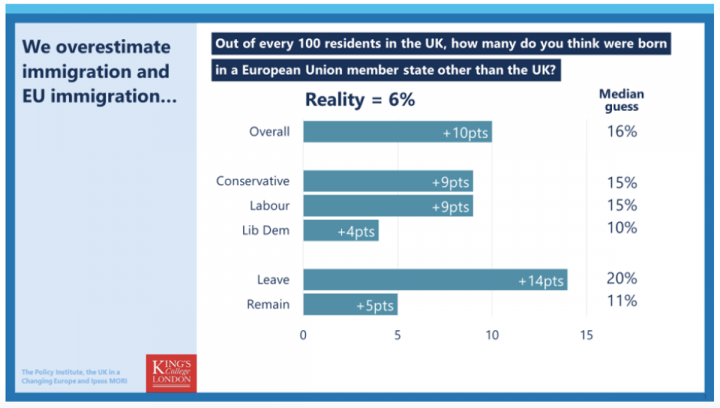

First, surveys show Britons think around a quarter of the population are immigrants, when it’s half that, at around 13%. And they think immigration from EU countries is nearly three times the actual level of 6%.

Author provided

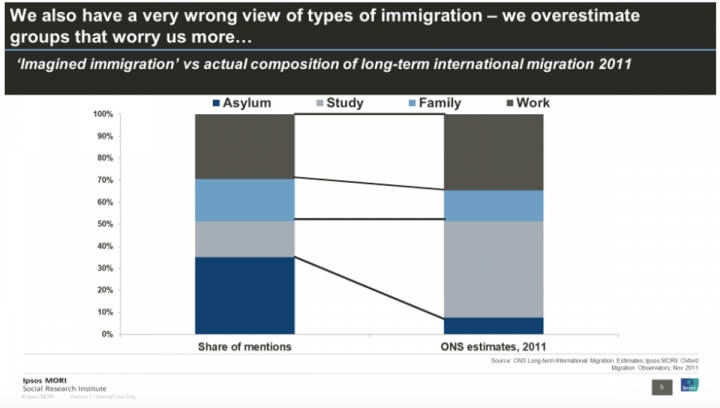

But it’s not just the scale but the composition that people get wrong. When we asked people what type of immigrants come to mind when they think of immigration, refugees and asylum seekers are the most mentioned, when they’re actually the smallest category of immigrants. People’s mental image is driven by media coverage and the tendency is to focus on the most desperate cases, not the more common categories of people who immigrate to work, study or be with family.

Author provided.

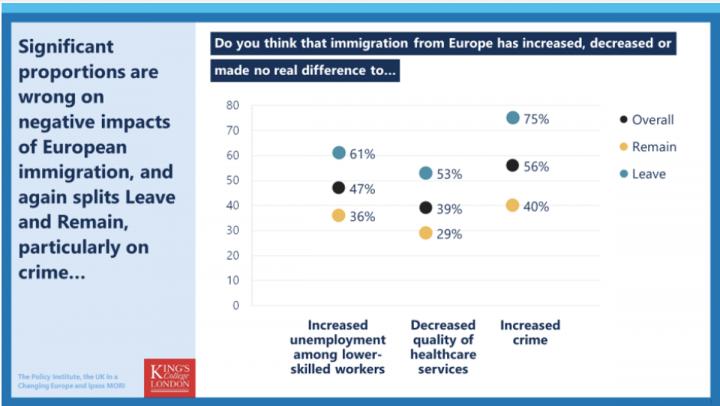

Most importantly, people in the UK are most wrong on the impact of immigration. Large proportions think that immigration increases crime levels, reduces the quality of the NHS and increases unemployment among skilled workers – when the best available evidence shows none of those are true.

Author provided.

Given British people’s mistaken belief in the link between immigration and crime it’s no surprise they think immigrants make up more of the prison population than they actually do. Those 1,000 people in our survey guessed 34% of prisoners are immigrants, when the reality is 12%, in line with their share of the population.

I’m very aware of the limitations of using facts to correct misperceptions, having written a book on why we get so much so wrong – and there are two key points to bear in mind.

First, we know that there is a complex relationship of cause and effect in our misperceptions. We overestimate what we worry about as much as the other way round. So our overestimates of immigration levels are as much a signal of our concern as a carefully calibrated estimate of reality. Our view of reality is coloured by our emotions, and this means that simple myth-busting alone will have limited impact.

Second, many have argued that the underlying driver of concern around immigration is not a cost-benefit calculation but a broader cultural concern that British society is changing too fast. So correcting the misreading of these facts by showing that immigration is actually good for our economy, public finances and services may miss the point.

Don’t avoid the facts

But neither of these are an excuse for not taking on these misperceptions with a positive, fact-based case. People are entitled to be concerned about the cultural impacts of immigration, but this does not mean politicians should avoid talking about the evidence of other benefits. The real issue has been the lack of political courage in making this case, and this extends back many years into previous Labour governments.

The approach in the 2000s was to say as little as possible about immigration and hope people didn’t notice – but it was disastrous. One of the few unifying factors in immigration attitudes was that British people felt it wasn’t being talking about enough: by 2011, only 11% of the public thought we were talking about it too much. This was epitomised in 2010 when Rochdale pensioner Gillian Duffy raised her immigration concerns with then-prime minister Gordon Brown. His initial response was to try to avoid the discussion and link the concern to bigotry.

But it’s not impossible to build a positive case, as the first minister of Scotland, Nicola Sturgeon, has increasingly done in recent few months, appealing to “national self-interest” by focusing on the contribution that immigrants make, particularly to an ageing society. Of course, there are limitations to this, as chancellor Angela Merkel found from taking a similar line in Germany.

But the UK as a whole is more characterised by an absence of any major political voices making the case at all. The tragedy is that this does not reflect the reality and variety of public opinion in Britain, which is more nuanced, balanced and increasingly positive about immigration than the loudest voices would lead you to believe. It’s time to tell the truth and trust the people.![]()

Bobby Duffy, Professor of Public Policy and Director of the Policy Institute, King’s College London

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.