“Rubbish in, rubbish out” – it’s as true of international organisations as it is of computers. And it’s an aphorism worth keeping in mind as we think of the Paris Peace Conference which began on January 18 1919 to address the new world order left after the end of World War I. However good a multilateral mechanism may or may not be, what really matters is the inputs that its member states make.

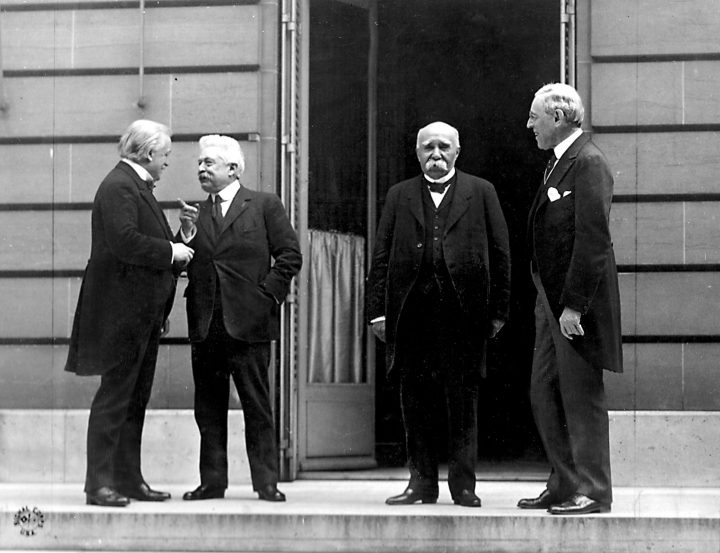

The representatives of the Great Powers were faced with the collapse of the Austrian, Ottoman, German and Russian Empires, burgeoning nationalism and the aftermath of the decimation of a generation of young men. The League of Nations was the capstone agreement of the Treaty of Versailles, which was signed on June 28, 1919. The idea was that the Great War would be the war to end all wars and that Europe would finally enjoy a lasting peace. Well, we all know how that went.

By the 1930s, the League had collapsed in the face of the Anglo-French refusal to confront the rise of totalitarianism, as well as US isolationism. Together, those factors prevented the League from working. In the 1940s, the Allies tried again, creating first a wartime alliance under a United Nations brand and then at San Francisco in 1945, the UN organisation we know today.

It was – and still is – easy to blame organisations for failing to keep the peace when the reality is that they lack resources to act in their own right and rely on nation states for power and authority. Thus the League of Nations was powerless to prevent the rise of aggressive nationalism. When Japan invaded Manchuria in the 1920s, the US and UK turned a blind eye. When Mussolini attacked Abyssinia in 1935, the UK refused to impose an oil embargo on Italy that would have stopped him in his tracks. And when Hitler, in his first militarist act, sent troops back into the Rhineland in 1936 – a region demilitarised by Versailles – the slightest intervention by France and Britain would have toppled him. But they sat on their hands, with fateful consequences.

New order for a new age

So why did the world return to a similar model after World War II when the League had failed so abysmally? The simple answer is that there was a consensus across the political spectrum that a return to the balance of power politics of previous eras was unthinkable. Technological development had created the potential for self-destruction. Two world wars, nuclear weapons and now climate change and wider environmental degradation require cooperation.

In the world of political philosophy, realist Hobbesians learned that they had to become utopian Kantians out of extreme realism. These two theorists are academic Olympians whose work has been used to educate generations: Hobbesians concerned with the uncontrolled violent behaviour of nations, Kantians traditionally hoping for a peaceful world. The forced lessons of cooperation generated by modern society means that the UN must be regarded as a realist necessity – not a liberal accessory to be abandoned when out of fashion. This tension is the defining issue of our time.

In trying to improve the realist resilience of the new UN, the founders made changes to the core structure. One problem the League of Nations had was that every member state had a veto. By contrast, one of the founding principles of the UN was that the five victorious powers – Britain, France, the US, China and the Soviet Union (the permanent members of the Security Council, with Russia subsequently inheriting the Soviet seat) each had a veto. This at least gives them an incentive to keep the show on the road. For any of the five to simply walk away would mean they would lose influence and let the remaining states hold power.

The first Soviet vetoes in the 1940s aimed to stop French imperialism returning to Syria and keep Fascist Spain out of the UN. Ever since the veto has been used to defend the interests of the five – notably the US over Israel and most recently Russia again, for different reasons, in Syria. But these common interests in using the system have reduced confrontation and the five have not fought each other – the key goal of the UN in 1945.

Avoiding self-destruction

Academic self-styled realists argue that international organisations and law will fail because they lack the power to enforce discipline in the way a nation state’s police can do. They miss the point. The fear of self-destruction is the disciplining factor. Nuclear deterrence is supposed to work because of Mutually Assured Destruction. This is why Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev were able to reach agreements that scrapped some of their most modern weapons and brought the Cold War to a relatively peaceful end.

The necessity of responding to the existential threat of the bomb by demilitarising foreign policy and supporting the UN was recognised by academic and political philosopher Hans Morgenthau in his final works. Sadly to this day, this work of a realist guru is ignored by nuclear weapons proponents who only use his early work in teaching which argued that states would and should use war as an instrument of policy, demonstrating again Einstein’s dictum that nuclear weapons have changed everything except the way we think.

As Morgenthau observed in the late 1960s, policymakers have taken the wrong course in trying to adapt nuclear weapons into traditional policy. He criticised US policy in NATO of making battlefield nuclear weapons available to be used by Allies such as Germany as part of efforts to make nuclear war winnable and to restrict the number of states with the bomb. Against the span of human civilisation, such attempts can only at best delay disaster.

Fortunately the efforts that ended the Cold War provide a set of prototypes for global weapons control to be pursued alongside climate control.

But the task of changing mindsets is daunting. Intensely militarised foreign policy has marginalised the UN and weapons controls. For all the reminiscing and displays of poppies to mark 100 years since the end of World War I in November 2018, the lesson “never again” has barely been heard. The poppy should have been set on the UN and EU flags – as these are the bodies created to prevent another world war and for which my parents’ generation believed they were fighting. The ugly and cowardly retreat into introverted nationalisms in recent years is an insult to the aspirations of the dead.

Morgenthau spoke of the necessity of cultural transformation to reduce and remove the role of the military and warfare now that, in his view, the bomb has made the use of force in world politics irrational. Feminist foreign policy is now starting to deliver on that.

The vital self-interest in responding to the UN’s weakness with political and material support is best summarised in the words of Dag Hammarskjöld, the UN leader who was murdered in 1961: “The United Nations was not created to take mankind to heaven, but to save humanity from hell.”![]()

Dan Plesch, Director of the Centre for International Studies and Diplomacy, SOAS, University of London

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.