By David Carroll Cochran January 20, 2019

This month marks the 100th anniversary of Dáil Éireann, Ireland’s Parliament. Amid the better-known events of a century ago that led to Ireland’s independence from its union with Britain, such as the Easter Rising or the island’s partition with the Anglo-Irish Treaty, the significance of Dáil Éireann’s founding on January 21, 1919 is often underappreciated. This is unfortunate, since it played a crucial role in the Irish Revolution’s outcome and was a path-breaking event in the emergence of nonviolent civil resistance methods over the last century.

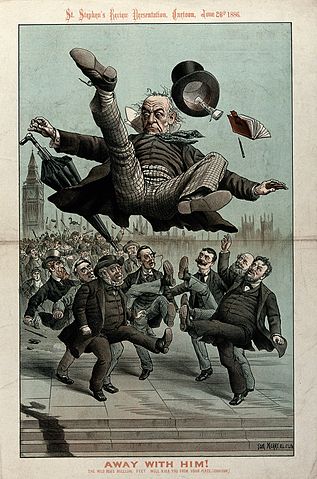

The usual story of Ireland’s independence struggle runs something like this: Revolutionary movements such as Wolfe Tone’s United Irishmen in 1798 or the Fenians in 1867 staged a series of violent “risings” against British rule that, while creating romantic nationalist heroes, were easily suppressed (Google “the battle of Widow McCormack’s cabbage patch” to get a sense of how they often turned out). These “physical force nationalists” were opposed by “constitutional nationalists” such as Daniel O’Connell and Charles Stewart Parnell who instead pursued a nonviolent reformist agenda within the British political system that gradually proved more successful.

O’Connell’s Catholic Emancipation movement won civil and political rights for Irish Catholics in the first half of the 19th century. Toward the end of the century, Parnell welded most of the British Parliament’s Irish representatives into the Irish Parliamentary Party, a block of votes that traded its ability to make or break majorities for concessions such as land reform that helped transfer farms from absentee British landlords to their Irish tenants. The chief goal of the constitutional nationalists was Home Rule, which would grant Ireland its own parliament and significant autonomy, though still as part of the larger British constitutional system and under some measure of British sovereignty. After a decades-long fight and several near misses, the British finally granted Home Rule in 1914, only to suspend it with the outbreak of World War I.

This is where momentum shifted back toward physical force nationalism. As majority-Protestant areas around Belfast in the north raised a militia and imported arms to resist Home Rule and keep the British union as it was, majority-Catholic areas in the rest of Ireland responded in kind. In an environment of increasing militarism, Patrick Pearse and a small group of armed rebels seized key positions in Dublin on Easter Monday in 1916 and proclaimed an Irish Republic completely independent of Britain.

The British military’s heavy-handed response — reducing the center of Dublin to ruin, executing the Rising’s leaders, imprisoning thousands not even involved, and declaring martial law — further radicalized the country. Within three years, the Irish Republican Army, or IRA, had launched a bloody insurgency campaign against British troops and local police units. The Anglo-Irish War, fought as a series of ambushes, assassinations and civilian reprisals, finally forced the British to cede Ireland its de facto independence in 1922, but only after partitioning off six counties that would remain part of the British union as Northern Ireland.

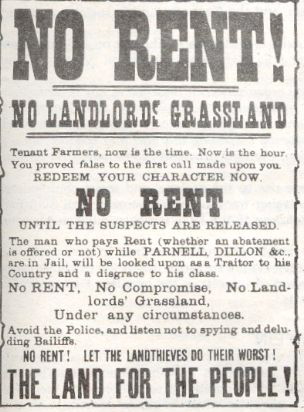

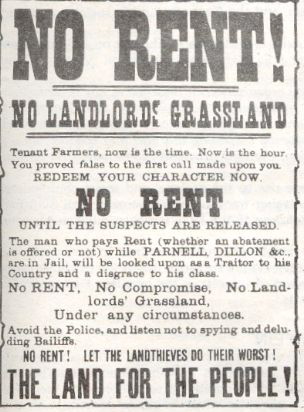

The usual story’s framing of violent versus reformist methods in Irish nationalism is true as far as it goes, but also incomplete. What it misses is a powerful third tradition of radical, extralegal, but still nonviolent resistance. In the 19th century, many rural communities, often organized by women in the Ladies’ Land League, refused to pay rent to British absentee landlords or work for their local land agents at harvest time. Indeed, our word “boycott” is named for Captain Charles Boycott, a land agent in County Mayo ostracized by his local community in 1880 during a noncooperation campaign.

An Irish Land League poster from the 1880s. (Wikimedia Commons)

Nonviolent methods grew more widespread leading up to and during the revolutionary period. In the years preceding to the Easter Rising, Dublin saw major industrial and transportation strikes; activists such as Helena Molony, arrested for destroying a picture of King George V during his coronation visit to Ireland, refused to pay fines and took jail sentences instead; and some Irish juries would not convict locals accused of opposing the British war effort during World War I. After the Rising, railway workers refused to carry British troops and munitions, other work-stoppages secured the release of political prisoners, and hunger strikes by Irish nationalists in British custody brought international condemnation down on the British government.

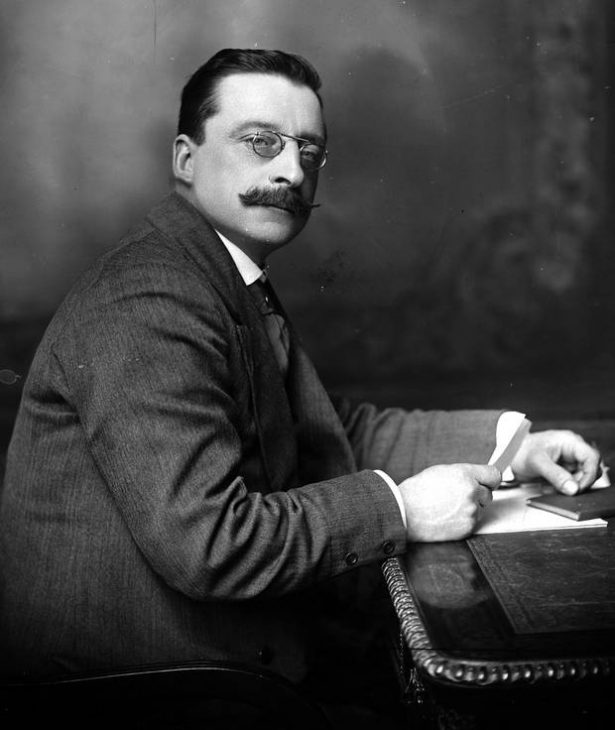

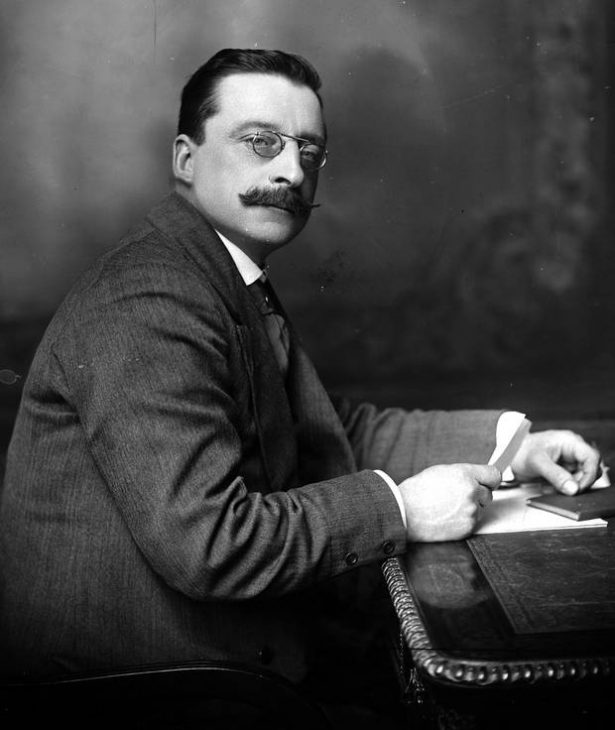

The key figure in this tide of nonviolent defiance was Arthur Griffith, the founder of Sinn Féin. Griffith was not a principled pacifist, but he believed nonviolent methods would prove more effective against British rule in Ireland. His was a nationalism that advocated dissolving the political and economic ties that linked Ireland to Britain by acting as if they no longer existed, an approach signaled by the name Sinn Féin, which is Irish for “Ourselves.”

Founded a decade before the Easter Rising, Griffith’s Sinn Féin movement came into its own in the revolutionary environment of the Rising’s aftermath. When the British government, desperate to replace soldiers killed at the front during World War I, decided to extend military conscription to Ireland in early 1918, Sinn Féin joined labor unions and Catholic clergy to coordinate a massive nationwide civil disobedience campaign. Almost two million people signed an anti-conscription pledge after Sunday masses that April 21. Arresting Griffith and other movement leaders only strengthened opposition, and ultimately the British found conscription unenforceable.

The anti-conscription campaign was a springboard for Griffith’s most innovative idea: using British elections themselves to select, legitimize and seat a rival Irish government outside the British system. When elections to the British Parliament, long delayed by World War I and featuring a newly expanded franchise with the inclusion of women voters, arrived in late 1918, Sinn Féin candidates, again backed by labor activists and Catholic leaders, swept to victory everywhere except the unionist strongholds in the north. Following Griffith’s policy of “abstentionism,” they refused to take their seats in the British Parliament and instead, acting as if British authority no longer existed, gathered at Mansion House in Dublin to declare themselves Dáil Éireann, or Assembly of Ireland, establishing the independent Irish government that exists to this day.

The Sinn Fein members elected in the December 1918 election at the first Dail Eireann meeting, called by Sinn Fein on January 21, 1919. Shown are (from l to r): 1st row: L. Ginell, Michael Collins (leader of the Irish Republican Army), Cathal Brugha, Arthur Griffiths (founder of Sinn Fein), Eamon de Valera (president of the Irish Republic), Count E. MacNeill, William Cosgrave and E. Blythe; 2nd row: P. Maloney, Terence McSwiney (Lord Mayor of Dublin), Richard Mulcahy, J. O’Doherty, J. O’Mahony, J. Dolan, J. McGuinness, P. O’Keefe, Michael Staines, McGrath, Dr. B. Cussack, L. de Roiste, W. Colivet and the Reverend Father Michael O’Flanagan (vice-president of Sinn Fein); 3rd row: P. War, A. McCabe, D. Fitzgerald, J. Sweeney, Dr. Hayes, C. Collins, P. O’Maillie, J. O’Mara, B. O’Higgins, J. Burke and Kevin O’Higgins; 4th row: J. McDonagh and J. McEntee; 5th row: P. B 1919 Ireland

While the British outlawed the Dáil as a “terrorist organization,” it continued to operate underground in accordance with its newly drafted constitution, appointing government ministers, sending diplomats to foreign capitals, and issuing bonds to raise money hidden from British authorities in sympathetic Irish banks. Operating as a parallel government, it attracted increasing allegiance from ordinary Irish people.

Crucial to its growing legitimacy was the Dáil’s ability to extend its authority down to local communities. In early 1920, Sinn Féin again swept elections, this time at the city and county levels, gaining control of many local governments that quickly flipped their loyalty to the Dáil, refused to cooperate with British tax collection, switched their purchasing contracts to Irish-owned firms, and closed workhouses associated with the hated British poor-law system. Even more dramatic was the creation of “Dáil Courts,” a multi-tiered parallel judicial system that spread across most of Ireland. British courts formally remained in place, but they essentially ceased functioning as enforcers of British law when local people instead began taking their disputes to the new Dáil judicial system that became, in the words of one local observer, “the only authority in the County.”

The nonviolent defiance of British authority led by Dáil Éireann existed alongside and overlapped significantly with violent methods during the Anglo-Irish War. Many nationalists supported both approaches and moved back and forth between the Dáil’s political resistance and the IRA’s military operations. But while mainstream, popular historical accounts give the violence more attention and credit for the Irish Revolution’s outcome — often through romanticized accounts of leaders such as Michael Collins — they underplay or miss entirely other critically important aspects of the struggle.

The historical evidence is clear that the Dáil’s campaign of noncooperation and parallel government did just as much or more to make Ireland ungovernable and force the British into negotiations. These actions eventually led to an independent country in the 26 southern counties and the formal handover of administrative power to the Dáil as that country’s legitimate government.

If the methods developed by Arthur Griffith (Picture Wikipedia) and Dáil Éireann are underappreciated in the usual story of Ireland’s independence struggle, the same is true of their contributions to the history of nonviolent civil resistance more generally. Few realize the impact Griffith’s innovative techniques for withdrawing authority from an occupier had on better-known nonviolent campaigns that followed him. India’s is the most notable. After attending a Dublin Sinn Féin meeting in 1907, Jawaharlal Nehru wrote: “They do not want to fight England by arms but to ignore her, boycott her, and quietly assume the administration of Irish affairs.” Leaders of the Swadeshi movement that organized boycotts of British goods praised Griffith as a “model.” And, perhaps most significantly, Gandhi himself cited Griffith’s direct influence on his own ideas, though he decried the later turn to violence by many Sinn Féin members.

and Dáil Éireann are underappreciated in the usual story of Ireland’s independence struggle, the same is true of their contributions to the history of nonviolent civil resistance more generally. Few realize the impact Griffith’s innovative techniques for withdrawing authority from an occupier had on better-known nonviolent campaigns that followed him. India’s is the most notable. After attending a Dublin Sinn Féin meeting in 1907, Jawaharlal Nehru wrote: “They do not want to fight England by arms but to ignore her, boycott her, and quietly assume the administration of Irish affairs.” Leaders of the Swadeshi movement that organized boycotts of British goods praised Griffith as a “model.” And, perhaps most significantly, Gandhi himself cited Griffith’s direct influence on his own ideas, though he decried the later turn to violence by many Sinn Féin members.

This influence shows how Griffith’s noncooperation techniques embodied by Dáil Éireann were important early contributors to one of the most significant developments of the last century: the emergence of organized civil resistance as an alternative to armed struggle. Indeed, as researchers such as Maria Stephan and Erica Chenoweth demonstrate, nonviolent civil resistance movements since 1900 are twice as likely as violent ones to succeed against an oppressive regime or foreign occupier.

And the case of Griffith and Dáil Éireann suggests such comparisons may actually understate the power of nonviolence. The Irish Revolution is an example of nonviolent strategies operating effectively, if more quietly, within an otherwise violent campaign, revealing how even seemingly successful violent movements may actually owe much of that success to overlooked nonviolent techniques operating behind the scenes. Dáil Éireann’s centenary, then, is a chance to celebrate this still-underappreciated revolutionary power of nonviolence.