Caroline Nye, University of Exeter for The Conversation

Japan brought in a controversial new labour policy at the end of 2018 which will open up blue-collar jobs to workers from countries such as Nepal, Thailand, the Philippines and Vietnam. The amendment to Japan’s notoriously restrictive immigration laws is expected to bring in an estimated 345,000 foreign workers within the next five years. It comes in response to the ageing workforce of Japan, where 28% of the population are over 65 and birth rates are falling.

Without migrants, Japan would face a very real danger of running out of workers. Is the UK next? Despite decades of free movement from the EU, an ageing workforce, uncertainty over post-Brexit immigration policy and an increasingly negative perception of Britain as a potential workplace have left many businesses feeling under threat.

A new report by the British Chambers of Commerce stated that recruitment difficulties in manufacturing are at their joint highest on record, with 81% of manufacturers reporting challenges in finding the right staff. The service industry is not far behind. At the same time, industries such as agriculture were reporting mild to severe labour shortages even before the EU referendum, an issue that appears unlikely to be dealt with in a meaningful way any time soon.

While the reasons for current labour shortages in the UK vary from industry to industry, they include tightening cash flow, low pay, poor conditions, lack of appropriate skills or poor work-life balance.

An ageing workforce

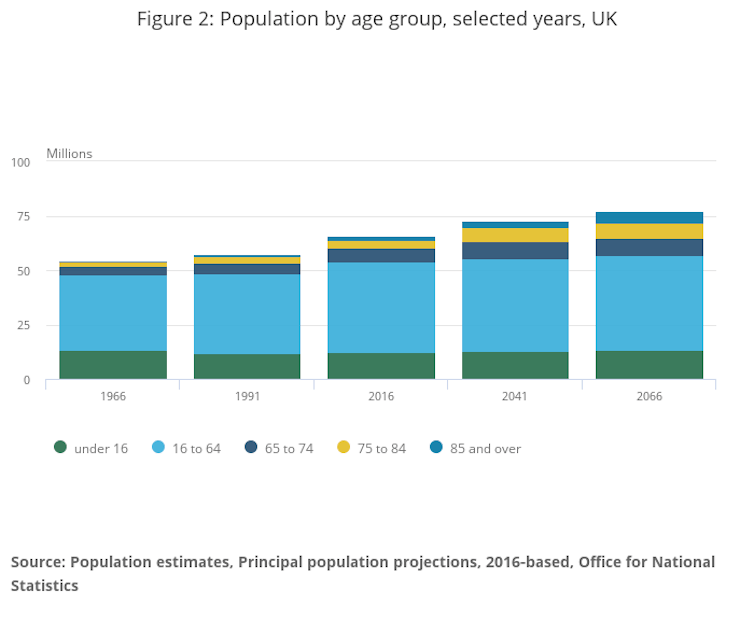

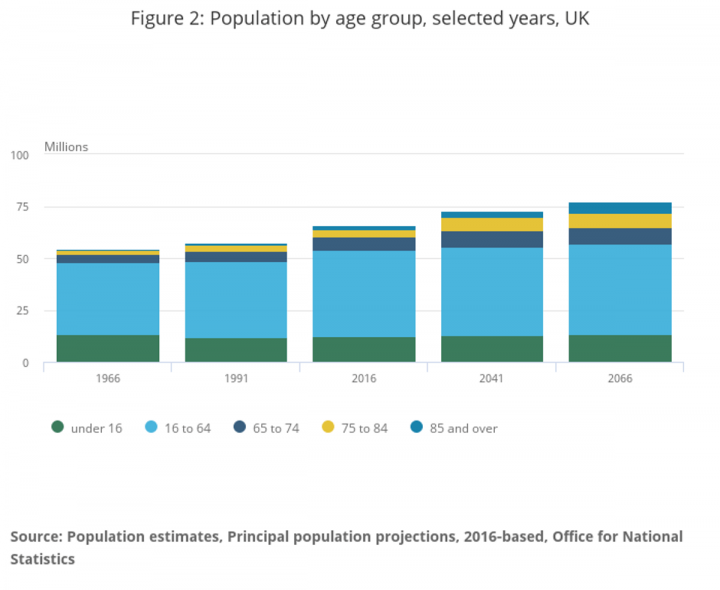

But over and above this, the major contributing factor to the current labour crisis is often that of the ageing population. Although over 65-year-olds currently make up only 18% of the population, the UK’s Office of National Statistics predicts that, much like Japan now, by 2066 at least a quarter of the UK population will be 65 or over, with more than five million of those being over 85.

Office for National Statistics

Industries that rely on young workers, such as hospitality, or those sectors which involve more physically demanding tasks, such as agriculture, already report that there simply are not enough people in the UK to do the work. While this is partly due to a dip in birth rates around the turn of the 21st century, the agriculture sector has experienced a progressively ageing workforce for several decades. This has come alongside a gradual decline in interest in the industry by domestic workers. Agricultural labour shortages are worsened by the fact that rural areas where farms are most in need of workers are often home to the highest populations of over 65s.

UK employers have become increasingly dependent on young people from the EU and beyond over the past 50 years. Brexit – and the likely immigration restrictions that will follow it – could be of enormous detriment to the UK labour market.

With the number of children being born in the UK hitting a 10-year low in 2017, the country needs to keep a close eye on Japan’s demographic time bomb and how it is affecting the country’s labour force requirements. Until now, Japan has imposed strict restrictions on immigration, a hangover from a long period when the country operated a “closed country” policy which encouraged ethnic and cultural homogeneity.

In a more recent recognition of its labour shortage crisis, the Japanese government opted to focus on encouraging more women into work, as well as increased activity by elderly people – and a parallel focus on increasing the nation’s birth rate. But the desperate need for workers led to the new labour policy being forced through Japan’s parliament despite significant opposition, as it was acknowledged that without foreign workers, positions simply could not be filled.

Wary of exploitation

Japan’s immigration schemes, such as the Technical Intern Training Programme (TITP), don’t have a good track record, with some critics describing it as akin to modern slavery. Set up in the early 1990s, the TITP was designed to provide training in technical skills, technology and knowledge for workers from developing countries such as Vietnam and the Philippines, in roles such as agriculture, fishery and construction. The scheme has become strongly associated with human rights abuses such as trafficking and forced labour.

The UK has its own history of migrant exploitation, especially in sectors such as agriculture. But it would be naïve to assume that by preventing the influx of foreign workers after Brexit, abuse and human rights violations related to food would simply cease. Moving the problem elsewhere does not necessarily make consumers less accountable for exploitation or human rights violations.

To safeguard against further exploitation, the Japanese government indicated that its new foreign worker policy will actively encourage companies to directly hire workers instead of using abusive or exploitative middlemen. It will also offer salaries equal to those of Japanese workers in the same position, language support and training. These are all strategies the UK might be wise to consider in any future immigration labour policy, especially agriculture – where rogue gangmasters have been known to create horrific living and working situations for some workers. Both countries have much work to do regarding their treatment of foreign workers.

According to a 2012 report by the World Economic Forum, “human capital will be the most critical resource differentiating the prosperity of countries and companies”. Unless the birth rate in the UK significantly increases, attracting back workers who are currently shunning the UK might ultimately prove an essential move in order that the shape of labour in the country doesn’t collapse completely.![]()

Caroline Nye, Associate Researcher, Centre for Rural Policy Research, University of Exeter

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.