By David Swanson

William James’ idea of the need to create a moral equivalent of war first struck me, decades ago, when I read about it, as about as sensible an idea as inventing a new way to punch yourself in the face. This was not purely because times have changed, because weapons have become more powerful, because the earth’s climate is collapsing, or because nonviolent activism has become widely understood as requiring courage, sacrifice, camarderie, dedication, discipline, and strength, without any of the counterproductive murder, maiming, destroying, occupying, hating, looting, pillaging, or stupidity.

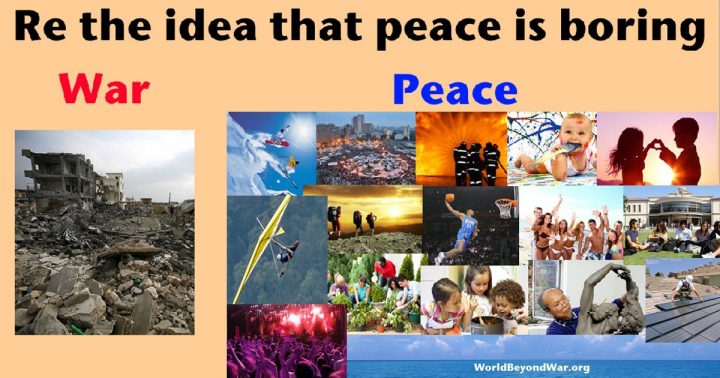

My reaction to the idea that we need to invent something else as good as war to replace its wondrous benefits was also based on the understanding, available to any child, of how unfathomably better peace is than war. Years ago, I made this top graphic as a response to being told that peace is boring:

If peace were as boring and deadening and degenerating as war mythology has alleged, wars wouldn’t be so often waged in the name of peace, and there wouldn’t be a peace pole in the Pentagon. While you can find people arguing for peace in one place in order to devote resources to wars elsewhere, you will be hard-pressed finding major peace movements declaring their devotion to bringing about peace in order to create eternal worldwide war.

That peace is better, that it includes all that is good, that it is culturally and morally and economically and environmentally and in every way superior to war is an idea that can be found in cultures all over the earth, now and in the past, and in Western culture as it’s traditionally understood, back through the millennia.

John Gittings’ book The Glorious Art of Peace highlights the existence of peace and the advocacy for peace through Western history. Among much else, he points to numerous works of written and visual art that contrast war with peace.

In Homer’s Iliad, just before the bloody finale in the Trojan war, the author pauses to describe in lengthy detail the depictions on Achilles’ shield, which include the contrast of a city at war and a city at peace. The case for Homer as an antiwar poet is certainly limited, but there’s something to it, and it would mean that my town of Charlottesville, Va., unlike some other unfortunate U.S. towns, has in it at least one monument that is not entirely a war celebration.

It seems quite likely that the ancient world understood far better than the United States today that war brings impoverishment, while peace brings prosperity. Below we see Eirene (Peace) bearing Ploutos (Wealth) in a Roman copy after a Greek votive statue by Kephisodoto (ca. 370 BCE).

In a town I used to live in, Siena, Italy, the town hall has in it a series of frescoes by Ambrogio Lorenzetti, often decribed as depicting good and bad governance. But that makes one think of a contrast between your admired local mayor and, say, the U.S. Congress. The major contrast depicted is in fact that of peace and war, which are literally and symbolically the content (the figure of peace is labeled with the word “Pax”) as well as the old name of the painting. We see peace in the city and countryside, and war in the city and countryside. And, no matter how much people love to shout “No justice, no peace” the reality depicted here is that in the absence of peace, any question of justice is ludicrous.

Gittings describes the city at peace. It includes no soldiers. “[T]he houses are well kept with flower pots in their windows; there are craftsmen at work, a tailor, a cobbler, a goldsmith, and a wine shop with people playing chess, while the fields outside are well cultivated, with a watermill, sheaves ready for threshing, farmers driving in their pigs to the market, and a hunting party out with their dogs.”

Gittings on the city and countryside at war: “[B]elow the flying figure of Fear, we see a city with empty streets and rough soldiers, houses in disrepair, women being raped, and, outside the city gates, abandoned fields, buildings set alight, and looters at work. The horned figure of Tyranny rules over the scene, with Justice bound at his feet.”

The purpose of contrasting peace with war on the walls of the room where Siena’s elected officials made public policy was the same as the purpose of hanging Picasso’s Guernica inside the United Nations building in New York (while the opposite purpose is served by covering that painting up during votes on backing wars).

Gittings quotes Pierre Ronsard from 1558:

“Would it not be best, oh noble soldiers,

Not to commit such a dreadful heap of crimes,

But to lay down your weapons and live well at home,

With your faithful and lovely wife in your arms,

To see your little children playing at her breast,

And clinging to your neck with their baby hands,

Ruffling your beard and tugging at your locks,

Calling you pap with a thousand little games?

Better surely than to live in camp and sleep on the ground,

Suffering from the summer heat and the winter cold,

Better to die old surrounded by your family

Than to find your tomb in the stomach of a dog.”

Rubens paints peace struggling to restrain war and the pestilence and famine with which it has ravaged Europe:

Rubens also paints the Goddess of Wisdom holding off War from Peace who nourishes Wealth:

We can, today, find similar contrasts, such as in this article and videos contrasting the wonders of peace in Damascus with the horrors of war there. But the author credits war with defeating war and creating peace, whereas we have actually learned that war brings, at best, very unstable peace.

Here’s a website contrasting participation in the U.S. Army with living a peaceful life. It’s meant to discourage enlistment. The ad below has proven unacceptable to any billboard company in the Land of the Free, and the struggle to get it accepted as a paid ad on social media continues: