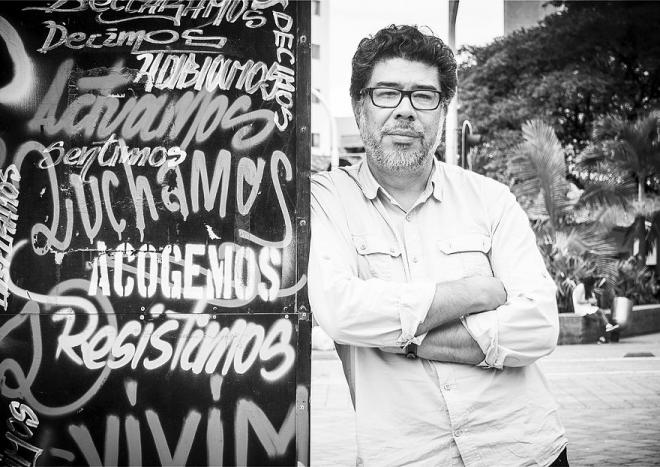

By Daniel Chavez

In recent years, many researchers and social activists from very different countries, like myself, have rediscovered the notion of the commons as a key idea to deepen social and environmental justice and democratise both politics and the economy. This reappropriation has meant questioning the vanguardist and hierarchical visions, structures and practices that for too long have characterised much of the left. This concept has resurfaced in parallel with the growing distrust in the market and the state as the main suppliers or guarantors of access to essential goods and services. The combined pressures of climate change and the crisis of capitalism that exploded in 2008 (a permanent and global crisis, which is no longer a series of conjunctural or cyclical recessions) force us to reconsider old paradigms, tactics and strategies. This means discarding both the obsolete models of planning and centralised production at the core of the so-called ‘real socialism’ of the last century and the state capitalism that we see today in China and a few other supposedly socialist countries, as well as the equally old and failed structures of present-day deregulated capitalist economies.

At first, the concept of the commons was disseminated by progressive intellectuals inspired by the work of Elinor Ostrom, the first woman to win the Nobel Prize in Economics, in 2009. Ostrom, an American political scientist, was a progressive academic, but could hardly be classified as a radical thinker or as a leftist activist. In the last decade, academics and activists from very diverse ideological families of the left have reviewed her contributions and have engaged in intense theoretical debates about the potential of the commons, based on the analysis of many inspiring prefigurative experiences currently underway.

Ostrom’s main contribution was to demonstrate that many self-organised local communities around the world successfully managed a variety of natural resources without relying on market mechanisms or state institutions. Currently, it is possible to identify various perspectives in the theoretical debates around the commons, but in general they all converge on the importance of a third space between the state and the market (which should not be confused with the Third Way outlined by Anthony Giddens and adopted by politicians as dissimilar as Tony Blair in Britain, Bill Clinton in the United States, or Fernando Henrique Cardoso in Brazil as a hypothetical social democratic alternative to socialism and neoliberalism).

Nowadays, a quick search in Google about the commons results in millions of references. Most definitions tend to characterise commons as spaces for collective management of resources that are co-produced and managed by a community according to their own rules and norms. We (TNI) have recently published a report on the commons in partnership with the P2P Foundation, in which we refer to this concept as the combination of four basic elements: (1) material or immaterial resources managed collectively and democratically; (2) social processes that foster and deepen cooperative relationships; (3) a new logic of production and a new set of productive processes; and (4) a paradigm shift, which conceives the commons as an advance beyond the classical market/state or public/private binary oppositions.

In Latin America and Spain, those of us interested in this field of activism and research must overcome a linguistic obstacle, since the translation of the concept of the commons from English into Spanish is not always easy or appropriate. This problem also appears in other parts of the world, so we often use the original English word to avoid confusion. Some of our friends and comrades use the concept of bienes comunes, but this term refers to ideas linked to the old economy or the social imaginary propagated by the church and other conservative institutions, without capturing all the richness, complexity and potential of recent theoretical developments and empirical processes around the commons. Obviously, the production of meaning in this field has already spread beyond the Anglo-Saxon world and there are already many people in countries of the South involved in this type of processes. That’s why the P2P Foundation and other friendly organisations have added a new word to the Spanish dictionary, procomún, while others (like myself) prefer to use the word comunes, which derives from a literal translation of the original term. From a similar perspective, many European or African activists prefer to use the English term instead of bens comuns (Portuguese), beni comuni(Italian), biens communs (in French), or gemeingüter (German).

Are the concepts of ‘the commons’ and ‘the public’ synonymous?

This question is the axis of heated theoretical debates, since it alludes to the old discussion about the nature and role of the state. The defenders of the commons who are most disillusioned with the left in government in several Latin American countries, particularly those linked to the fundamentalist autonomist current (like many of my friends in the Andean region, mainly those who are involved in struggles around the rights to water or energy) are convinced that the state should not assume any role and that the social order should be restructured by transferring political and economic power to self-organised local communities. Other researchers and activists (including myself, something that’s not surprising having been born in a country as state-centric as Uruguay) retort that such a contradiction is artificial and that we should at the same time expand the reach and influence of the commons – for example, by creating and interconnecting new types of authentically self-managed cooperative enterprises– and democratising or ‘commonising’ the state – for instance, incorporating workers and users into the management of existing state-owned enterprises or creating new public-public partnerships for the provision of essential public services.

My friend Michel Bauwens, a Belgian social activist internationally recognised as one of the most creative and influential thinkers in this field, often highlights the importance of what he has characterised as the partner state. From his (and mine) perspective, the state is perceived not as the enemy, but as an entity that could provide local communities and self-organised workers with the institutional, political or economic power that would be required for these processes to reach their maximum potential in the framework of the political and economic transition that we need. It also means, among several other possibilities to be considered, the provision of financial or in-kind support for cooperatives or other initiatives inspired by the notion of the commons.

The idea of the partner state is in line with some relatively recent theoretical debates among Marxist thinkers. Today, and especially after a series of counter-hegemonic governments that we have had in Latin America, we’re already very aware that the contemporary state is not simply that “committee for the management of the common affairs of the bourgeoisie” that Marx and Engels referred to in the Communist Manifesto. Neither Marx nor Engels were interested in developing a unified or integral theory about the state, so we should not interpret their statement (from the year 1848!) literally,. In the 1970s, Nikos Poulantzas and other non-dogmatic thinkers began to rethink the institutional framework of capitalist societies and argued that the state should be understood as a social relationship and not as an abstract entity floating above conflicting social classes, and added that the transformation of state institutions could be possible in the context of a “democratic way to socialism” (opened by the government experience of Popular Unity in Chile and brutally repressed by a military coup in 1973). More recently, Bob Jessop has shown how, although the state has a strong structural bias towards the reproduction of social relations, it’s also influenced by the totality of social forces, including counter-hegemonic struggles. My perspective of analysis on the state and the commons is very influenced by Jessop, and also by David Harvey, when he argues that a big problem on the left is that many – pointing to John Holloway and other proponents of the thesis of “changing the world without taking power” – think that the capture of state power wouldn’t be of much importance in emancipatory processes. We must recognise the incredible power accumulated in the institutions of the state and, therefore, we shouldn’t underestimate the importance of state institutions; in particular when there’re opportunities to enable the expansion of the commons.

To those who are interested in deepening the knowledge of contemporary theoretical debates on the state and the commons, I would recommend reading our comrade Hilary Wainwright, the British political economist with whom I co-coordinate the TNI New Politics Project. A few years ago Hilary wrote a beautiful book, Reclaim the State: Experiments in Popular Democracy, where she argued the need to ‘occupy’ state institutions while, in parallel, we organise ourselves to create and connect new political and economic institutions rooted in local communities and workers’ collectives. Her books, the one mentioned here and more recent ones, are based on the detailed investigation of positive examples of commons-related initiatives across the Globe.

In recent years, within the framework of our New Politics project, Hilary, myself, and many other activist-scholars from different regions of the world have tried to make sense of a substantial shift in emancipatory thinking. Until not long ago, the economic policy of much of the left included the proposal of nationalisation of key industries. Nowadays, and maybe influenced by the recognition of the failures or shortcomings of nationalisation in places like Venezuela (where in recent years there’s been a recentralisation of political and economic power in the hands of the bureaucrats and military that control the reins of the state, with very negative in terms of lesser autonomy and influence for popular organisations and with very bad indicators in the management of nationalised companies) many of us are more interested in the design of a new economy based on cooperative relations, in which state institutions would play a facilitating and protective role. We emphasise the importance of public ownership of public services and productive infrastructure, but only as long we ensure a significant level of decentralised ownership and management; for example, in the provision of water and energy services and in the production of a vast range of goods through networks of self-managed ventures.

This perspective also means a deeper and more serene examination of the ambivalent consequences of the scientific and technological changes currently underway. We already know that the emerging forms of organisation and control of information and communication technologies and distributed production constitute a very contested space, in which a few transnational corporations (I’m thinking of Uber, Airbnb and other examples of the wrongly called ‘sharing economy’) financialise and benefit from precarious workers, the users of social networks and independent software programmers – with negative impacts on unions’ power and on the quality of work – but we should also be able to recognise that the same technological developments could be beneficial for the (re)creation of truly solidarity, democratic and self-managed forms of ownership and management. Around the world, we can see the emergence of a new generation of workers who use their technological knowledge to launch new enterprises and networks based on the principles of the commons and coordinate and collaborate among themselves, transcending economic sectors and geographical borders, and being ethically (and increasingly also politically) aware of the new social and economic order they’re creating.

How would you appraise the so-called ‘pink tide’ in Latin America vis-à-vis the commons?

My personal perspective on these issues has evolved, as I tried to understand the arguments of comrades from other Latin American countries who posed a very strong critique of the statist political culture prevalent in some political and academic circles of the region. Like many Uruguayans, it was hard for me to assimilate the positions of compañeros like Pablo Solón in Bolivia, Edgardo Lander in Venezuela, Arturo Escobar in Colombia, Maristella Stampa in Argentina, or Eduardo Gudynas himself in Uruguay. They (and many others) are strong critics of ‘development’, and in particular of its ‘(neo)extractivist’ component. In short, my critique to them focused on two aspects: their staunch criticism of the state, and their inability to formulate alternatives or proposals to transcend the reality that they criticised. With the passage of time, and after many and agitated discussions with Pablo and Edgardo in workshops at the World Social Forum, seminars of our New Politics project and other similar spaces, I could understand that their criticisms of the state (not always so homogeneous nor so acidic as I perceived them) were not that far from my own criticism of the Latin American left, and I also ended up realising that indeed there were proposals embedded in their criticisms.

My position on these issues has also been influenced by my increasingly pessimistic interpretation of the outcomes of our progressive of left governments. After having followed very closely the processes of Venezuela, Ecuador, Argentina, Uruguay and Brazil, and to a lesser extent also those of Bolivia and Nicaragua, I think we should ask ourselves up to what point is it possible for the left to get involved in government without losing autonomy and our utopian perspective. In other word: is it possible to operate within the state apparatus without being caught in the demobilising logic of institutional power? Unlike some of the friends I mentioned before, I don’t have a single or categorical answer to such question. I still believe that the state has a very important role to play, but I’m also convinced that it is now imperative for the left to get rid of its obsolete state-centric vision and open up to fresh perspectives like those of the commons.

For the Uruguayan left, such transition could be difficult, if we consider the heavy weight of the state in our society, politics, economics and culture. A significant difference between Uruguay and most other countries in the region is its long tradition of strong and efficient state-owned companies, which are highly appreciated by the population. In Uruguay, people perceive the state as a catalyst for development and guarantor of equity and social integration. On the other hand, the transition could be made easier if we consider the already high significance of workers’ and housing cooperatives. I grew up in a mutual-aid housing cooperative, so I might not be entirely objective. And we know that not all cooperatives are well managed or are internally democratic or participatory, but when we compare the reality of the Uruguayan cooperative sector with other countries of the region and the world, it’s clear that we already have a very fertile terrain for the development of the commons.

From a purely theoretical or ideological point of view, many components of the current global debate around the commons wouldn’t be a novelty for the Uruguayan left. If we look at several parties that compose the ruling coalition Frente Amplio(Broad Front), we realise that parties as different as the Progressive Christian Democrats (PDC, the advocates of the thesis of socialismo autogestionario, self-managed socialism), the People’s Victory Party (PVP, in line with their libertarian roots), or the Socialist Party (PS, with their proposal of transition from co-management to self-management, which the party has been advocating since 1930, when it demanded workers’ control of the economy) have been for a long time formulating programmatic ideas that transcend the limits of statism.

In other countries of the region, it would seem that the proposal of the commons would be more compatible with the governmental discourse. In fact, the proponents of the commons in Europe often refer to the concepts of vivir bien (living well) or buen vivir (good living), which came from Latin America. These concepts became popular on a world scale as a supposed alternative paradigm to capitalism. The concepts of suma qamaña and sumaq kawsay have their roots in the economic and societal models developed over centuries by the indigenous peoples of the Andean and Amazonian regions, prioritising forms of production more horizontal and in harmony with nature. The translation (or ‘export’) into other languages and cultures is problematic, but in the countries of origin the significance of these concepts can be debated as well. Bolivia and Ecuador, during the governments led by Evo Morales and Rafael Correa, incorporated the notions of living well and good living in their respective constitutions and policy guidelines, but the policies implemented have not always been coherent with the spirit or with the letter of the new legal and institutional framework. In Ecuador, in the framework of the very radical turn to the right performed by president Lenin Moreno in recent months, the discourse of buen vivir (which sounds beautiful and guarantees a left patina) is being used to provide justification for an impending wave of privatisation and corporatization of public services. In Venezuela, there was also much talk around self-management and people’s power, and considerable resources were allocated to the creation of cooperatives and associative ventures of a new type, but in practice very little progress was achieved; the rentier model based on the exploitation of a single resource – oil – deepened during the governments of Hugo Chávez and Nicolás Maduro, and its current exhaustion is the most important factor to explain the political, economic and social crisis that the country suffers today.

What are the organisational and programmatic challenges of the left for the integration of the idea of the commons into its political platform?

To answer this question, I should start by clarifying that I do not believe that the promotion of the commons should be the only strategy of the left. I believe that we must embrace the emancipatory vision of the commons, but without forgetting the role of the state and the need to respond to the very urgent problems of large sectors of the population. I agree with the criticisms of the hegemonic model of development and support the struggles against extractivism. I also tend to agree with many elements (not the whole package) of the emerging theorisation around the concept of degrowth – which is already very influential among European left circles, but not very significant within the Latin American left. But I disagree with visions such as Escobar’s when he speaks of “underdevelopment” as a mere “narration”, presenting it as an abstract concept that the colonialists would have elaborated and spread for the colonized to repeat. We can’t ignore the terrible rates of poverty, exclusion, and poor access to basic goods and services that still affect millions of Latin Americans. Our region should be incorporated into the global fight against climate change, and we must promote new forms of organisation and production that preserve the ecological balance, but we must also respond to social demands in the context of a quite likely deterioration of the economic situation in the short or medium terms. In that sense, I believe that the impulse to the commons must be framed within a broader strategy of growth, different from that offered by predatory and savage capitalism.

Thinking about the specific conditions of Uruguay, and based on data and projections published by local researchers, it should already be evident that the promotion of mega-projects like the huge paper mills run by Finnish corporations, or the already privatisation of the wind segment of the energy sector, don’t constitute the most appropriate developmental strategy. I would have preferred that the effort made by the government to convince us that the attraction of direct foreign investment and the liberalisation of trade are the right path would have been accompanied by serious studies sustained by reliable information to appraise the pros and cons of two different strategies: supporting large private investment on the one hand, and the promotion of the local and popular solidarity economy on the other. What would be the impacts of redirecting the tax exemptions and the large explicit or covert subsidies received by large transnational corporations if all that money were used to support cooperatives and other associative enterprises rooted in the national economy? I don’t have concrete answers to these queries, but I know that other Uruguayan economists and social researchers also raise similar questions and could provide objective and relevant information to deepen this exchange.

How to incorporate the commons within a political project that aims at the de-commodification of public services?

In Latin America we have many valuable examples of de-commodification of public services, past and present, that we should reconsider in the framework of current exchanges around the commons. A few years ago, during the heyday of what we then praised as the Bolivarian ‘revolution’, I worked in Venezuela and I was able to appreciate very closely the emergence of multiple processes of popular self-organisation in which millions of people participated. I’m referring to the mesas técnicas (people’s technical committees), the consejos comunitarios de agua(community water councils), the consejos comunales (communal councils) and the comunas (communes). Unfortunately, most of these processes are no longer in existence or in terminal crisis. Individualism and competition has been stronger than solidarity and cooperation in the responses to the crisis that Venezuela is experiencing today. This is a sad realisation, which forces us to question ourselves about the reasons and the conditions that made possible the erosion of processes that many of us considered very strong and even irreversible. A large part of the communal and participatory initiatives that had emerged in the most fecund years of the Venezuelan transition have gone into rapid regression when faced with the loss of the resources provided by the state (of which they had become dependent), in the context of the terrible deterioration of the social and economic situation. I think that many lessons can emerge from Venezuela, both on the potential of the commons and on the fragility of processes of this type. It also forces us to rethink the limits of ‘revolutionary’ political projects that are excessively focused on the state.

At the international level, and taking as a basis for analysis the European reality – which is the one that today I know better, since it’s my place of residence, activism and research – I believe that Latin Americans could ‘import’ some interesting ideas from current European exchanges on alternatives to commodification and corporatization. The side of the European left most active side in the promotion of the commons is that linked to struggles around the right to the city and the citizen platforms that won local office in several Spanish cities. Today, an important part of the European left perceives the city as the privileged space for political, social and economic experimentation, without seeing cities as isolated entities or at the margin of processes aimed at changing the state on a national scale, but recognising their growing significance in the new regional and world order. It’s not by chance that the fight against climate change or for the recovery of public services are led by networks of progressive local governments. Barcelona En Comú, the citizen coalition that now governs the Catalan capital, in particular, is a very powerful source of inspiration of regional and world importance. The political influence of Barcelona today is comparable to the hope that Porto Alegre, Montevideo and other Latin American capitals had been generated in the 1980s and 1990s, when the left began to experiment with participatory budgeting and other innovative policies for the radicalisation of democracy at the municipal level. Barcelona is today a laboratory for the design and testing of multiple initiatives inspired by the principle of the commons.

Another possible source of inspiration could be the current program of the British Labour Party. Since Jeremy Corbyn became party leader, Labour has become much more radical than our Frente Amplio and most other left parties in Latin America and Europe. The Labour Party has a proposal for renationalisation that’s much more advanced than similar initiatives applied or proposed anywhere else in the world. In the specific case of the energy sector, Corbyn and his party propose to bring back the sector into public hands, so that the country’ energy becomes environmentally sustainable, affordable for users, and managed with democratic control, as stated in the programmatic manifesto launched last year. But renationalisation, from this perspective, does not simply implies that the state retakes control by going back to the obsolete state-owned companies of the past, but rather the combination of different forms of public ownership and management. In short, Labour proposes not merely to re-nationalise companies that had been privatised during Thatcherism and Blairism, but to reconvert the big banks and other financial institutions that during the crisis had been saved from bankruptcy with public monies into a network of local banks based on mixed ownership (state and social), or the creation of new municipal utilities. The party is committed to create new municipal utilities, inspired by some socially-owned companies already in operation – such as Robin Hood Energy in Nottingham – or by popular campaigns – such as Switched On London – that propose the de-privatisation of power through the launch of new public enterprises, rooted in a more democratic type of management based on the active participation of users and workers, being environmentally sustainable, and securing services with affordable rates for the entire population.

Daniel Chavez, a TNI fellow, specialises in left politics, state companies and public services. He is an active contributor of the Municipal Services Project (MSP) research network, has contributed to Alternatives to Privatization: Public Options for Essential Services in the Global South (Routledge, 2012) and has co-edited The Reinvention of the State: Public Enterprises and Development in Latin America and the world.