Anna Jackman, Royal Holloway for The Conversation

One of the amazing things about the recent drone incident at London Gatwick is that the appearance of two unmanned aerial vehicles flying into operational runway space prompted the closure of Britain’s second-busiest airport for more than a day. With further sightings of drones, Gatwick only reopened to limited service after a 36-hour interruption, and those responsible for operating the drone remain at large.

With more than 110,000 passengers on 760 flights due to depart Gatwick on just one of the affected days, these drone incursions have left a trail of disruption behind them.

This is by no means the first incident of drones causing problems at airports – there have been similar incidents in Canada, Dubai, Poland and China. But the event at Gatwick is unusual in both the length of its duration and the presence and repeated use of multiple drones.

The growing availability and affordability of consumer drones means that risks to airports, and other secure spaces will rise – and the counter-measures currently deployed against them leave room for improvement and need to be more widely adopted.

Unclear motives

A study by the Remote Control Project estimates that around 200,000 drones are being sold for civilian use around the world every month. Readily available from a range of online and high-street outlets, drones are becoming more commonplace and more affordable for the hobbyist.

As they move from a niche product to a more mainstream device, they have also caught the eye of growing number of hostile groups – and state militaries as well as terrorists and other non-state actors are increasingly deploying drones on the battlefield.

The Islamic State, for example, has used drones to drop explosives, to observe and direct fire for others, and to capture footage for propaganda. Elsewhere drones have been used to cause disruption at home, such as the drone “assassination attempt” on the Venezuelan president, Nicolas Maduro, in August 2018.

The incident at Gatwick has not been labelled a “terrorist event”, but whether “criminal, careless, or clueless” it demonstrates that even consumer drones can cause risk to life and economic activity, despite being unarmed.

Deliberate disruption

Sussex Police have referred to the at-large drone pilot’s actions as “deliberate disruption”. At a recent Countering Drones conference I spoke precisely about how both consumer and DIY drones may be flown and modified to do this. Delegates at the conference debated, lamented and reflected on the potential responses to such deliberate disruptions, considering their potential effects on crowds, sensitive infrastructure, or at political events.

The presence of an unknown drone can both unnerve and cause panic – and this could be further amplified, considering the potential for drones to be outfitted with weapons, or means to disperse hazardous materials.

In seeking to future proof how we think about drones and their risks, it is worth considering how drone technology and software is developing. There are now intelligent flight modes that allow drones to track and follow designated individuals, basic swarming functionalities that allow multiple drones to act in coordination, and the livestreaming of images to social media, meaning that drones can potentially be used for live propaganda.

Countermeasures

A question frequently asked is, for example at Gatwick, why don’t the police shoot down the drone? While armed police were present and joined by specialists from the armed forces, apprehending operators remains difficult because of their distance from their drone. It is dangerous to shoot down a drone due to the risks of falling objects and stray bullets, but due to their small size drones are also difficult to detect before they are close enough to become a problem.

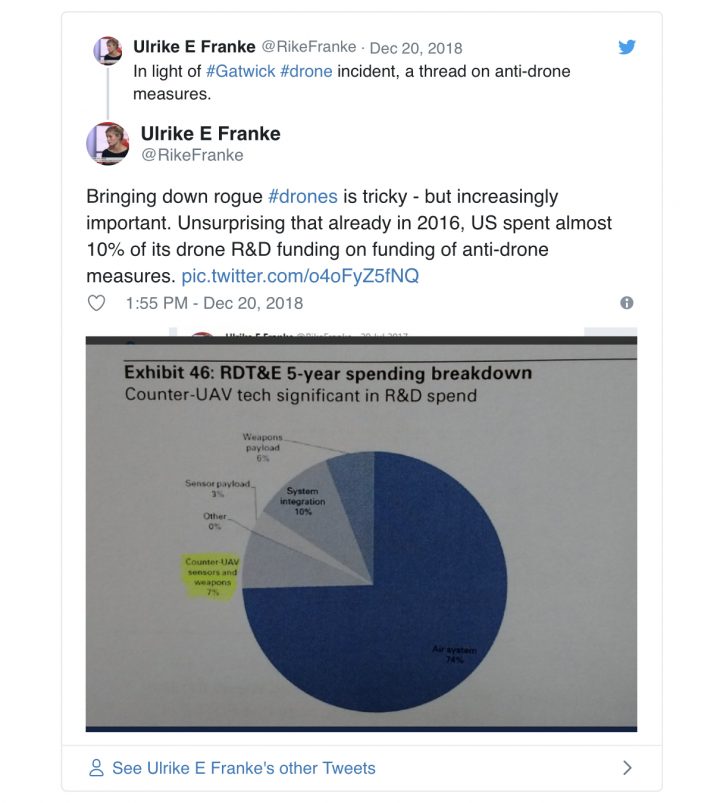

There has been however a boom in the development of a range of countermeasures designed to stop drones. A recent report by Arthur Holland Michel of the Center for the Study of the Drone profiled more than 230 products produced by 155 manufacturers designed to counter drones.

Among them are those which seek to detect and alert users of approaching drones, to impede and stall drones through GPS and radio jamming or the embedding of electronic tagging and geo-fencing software, which prevent drones from being used near sensitive locations such as airports, prisons or power stations. There are also ways to to intercept and capture the drones using net-equipped drones and guns. Dutch national police have even trained eagles to intercept drones.

But counter-measures are inherently limited due to their implementation cost and cost-effectiveness – as well as by legislation that governs the electromagnetic spectrum in which they function. Numerous reports have shown how preventative defences built into drones such as geo-fencing or altitude restrictions can be tampered with, overridden, or even simply switched off.

So there remains a serious difficulty in enforcing drone use and apprehending those that act illegally, despite recent convictions of those using consumer drones to transport contraband into UK prisons. It’s not the first time Gatwick Airport has had to contend with an errant drone, but this occasion should be a wake-up call to the need for reliable and affordable counter-measures, and the need to think more creatively about the potential risks posed by (multiple) drones more widely.![]()

Anna Jackman, Lecturer in Political Geography, Royal Holloway

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.