100 years since (some) women won the right to vote, they’re still marginalised in corridors of our power – and facing a backlash there too.

Visitors at Westminster Hall are now welcomed into the British Houses of Parliament by a stained glass installation called “New Dawn”. Created in 2016 by the artist Mary Branson, and measuring six metres high, it’s an eye-catching, colourful celebration of the mass movement for women’s suffrage in the UK.

But how did Westminster exclude women before and after the 1918 Representation of the People’s Act? (Which widened the right to vote to include women over 30 years old, along with all men; it wasn’t until 1928 that all women won this right). And how does British politics continue to exclude women today?

Before an 1834 fire necessitated the reconstruction of the Palace of Westminster, women weren’t allowed to set foot in the House. Men – including those not permitted to vote – could attend debates and sit in the public gallery.

Women were shut out of the business of politics altogether, and couldn’t bear witness to the debates and discussions that happened between men in power.

Some celebrated women still got involved in politics. Georgiana Spencer, the Duchess of Devonshire, for example, actively campaigned for male MPs, leaders and political parties. But even a woman as influential as Spencer wasn’t allowed into parliament to watch the men she advocated for debate.

Man-made laws have never prevented women from fighting for their rights. In the early 1800s, women found a way to break through the patriarchal barriers that kept them out of the Houses of Parliament. They climbed into the building’s loft and watched the day’s debates through an air vent.

At first, these women were removed from their perch by parliamentary guards. But, over time, their presence became known and even tolerated. Political activists brought influential women to the loft to watch the debates below, including the UK’s first woman doctor, Elizabeth Garrett-Anderson.

Women had breached the House – and would continue to do so.

A 2018 protest calling for women’s equal representation in parliament.

From the roof to the floor

Following the great fire of 1834, the restored Houses of Parliament welcomed women into the public gallery for the first time.

No longer trapped in the smelly, hot and confined space of the loft, they could now watch debates from a gallery behind the speaker’s chair. But they still didn’t sit on equal footing to men, and were confined behind sturdy metal grills.

The all-male MPs were concerned that the presence of women would be “distracting”; their bodies were hidden away in order not to divert the men’s attention from the business of the day.

This seclusion of women in parliament in the nineteenth century reflected elements of Victorian prudery – the old myths about men being overwhelmed by the sight of a shapely ankle. How far have we moved on from this?

The prominent conservative journalist Toby Young, for example, famously tweeted about the “serious cleavage” of an MP sat behind then Labour leader Ed Miliband.

How welcome are women in British politics today, when their bodies are still scrutinised and treated as distractions – much as they were in the 1840s?

Women in the House

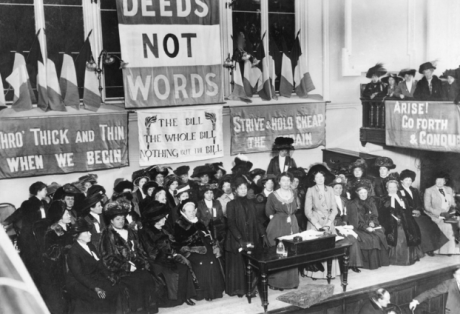

In the early twentieth century, militant suffragettes chained themselves to the metal grills in parliament during a protest – using a structure designed to exclude them from political debates as a tool in their struggle for inclusion.

Westminster’s walls – or in this case, its grills – were starting to fall.

On 21 November 1918, a law was passed allowing women to stand for election. It was a historic change. However, due to her political affiliation, the first woman MP, Countess Constance Markievicz, refused to take her seat.

This act of protest is one that members of the Northern Irish Republican party Sinn Fein – to which the Countess belonged – still follows today, in protest of parliament’s jurisdiction in Northern Ireland and its oath to the Queen.

As a result, the Houses of Parliament didn’t have to worry too much about including women in their space – at first. But that soon changed, with the election of Lady Nancy Astor in 1919.

Now, there was a Lady Member of the House, who required a Lady Members’ Room in which to work and rest.

Unlike the Members’ Room for men, it was tiny. As more and more women MPs were elected, they had to sit on the floor in increasingly crowded conditions, notebooks balanced on their knees, struggling to get work done.

Women MPs from opposing parties had to work in close proximity. While one assumes there was some camaraderie between them, it’s hardly practical to prepare for political debates cheek-by-jowl with the opposition.

The crowded conditions of the Lady Members’ Room sent a clear message to women MPs: women were to be tolerated in parliament, not welcomed.

Women were to be tolerated in parliament, not welcomed.

Throughout the twentieth century, more women entered parliament, but their numbers remained low. Then came the historic 1997 election in which 120 women won seats – changing the makeup of British politics forever.

This election doubled the number of women in parliament overnight (only 60 had won seats in the previous 1992 elections). More than 80% of these 1997 women MPs came from the Labour party (101), followed by the Conservatives (13), the Liberal Democrats (three) and the Scottish National Party (two).

The larger number of women MPs required significant changes to the Houses of Parliament. An old men’s changing room was turned into a women’s loos. A decade later, a parliamentary bar was closed down and replaced by a crèche.

The presence of the formerly excluded in such greater numbers was symbolic and appeared to demonstrate that, finally, women were seen as the equals of men. But it wasn’t so simple. Forces still worked hard to exclude women.

2018 March for Women in London.

“Babies in a playpen”

After the 1997 ‘Labour landslide’, women held 19% of the seats in parliament, which was remained dominated by adversarial, aggressive debates and what some consider a very “male” or macho style of politics.

One woman MP elected that year told Professor Sarah Childs that “a premium is put upon what is predominantly a male style of political practice, which is quite aggressive… a debating society style which men are often much better at, have more confidence in doing and are taught more to do”.

Many women MPs have been disheartened by the old-style politics that relied on masculine models of elite Oxford and Cambridge university debating societies. They told Childs how parliament was still a “boys club” that relied on “hitting the bars together and drunks going through the lobby at 10 pm”.

They argued that women’s different experiences should change how MPs conduct politics, moving away from what one called “babies in a playpen” debates to a more “feminine” or feminist approach.

But women found their colleagues punished them for not adopting the macho style that had shaped the House for hundreds of years. One MP told Childs how party whips said she was “too quiet”, without “enough barracking and shouting”.

Women MPs were accused of “whinging” about “laddish” behaviour and depicted in the media as unable to cope with the pressures of politics. This re-enforced assumptions about the unsuitability of women for political life. Women were in the House, but too many still questioned whether they should be.

Women were in the House, but too many still questioned whether they should be.

An egregious example of this behaviour came in 1997, when those 120 women entered Westminster.

According to a report in The Times newspaper, they “were subjected to sexual harassment: comments were made about women MPs ‘legs and breasts’ and when women MPs spoke in debates it was reported that Conservative MPs ‘put their hands out in front of them as if they are weighing melons’”.

As we know from recent #MeToo allegations, which led to the resignations of former defence secretary Sir Michael Fallon and former deputy prime minister Damian Green, parliament has not yet eradicated such behaviour.

Sexual harassment within the UK’s political structures remains a deliberate tactic to exclude women and reinforce male dominance in Westminster.

Women representing women

The election of more women into parliament has created new spaces where so-called “women’s issues” can be discussed in political life.

Before the 1997 election, some women MPs told Childs that “ministers were already responding to the pressure emanating from women”, and that “issues previously classified as ‘women’s issues’ such as education and the welfare state, [had] been prioritised as central issues by the current government”.

In her foreword to Childs’ book, New Labour’s Women MPs, the Labour MP for Peckham Harriet Harman wrote about how women’s dramatically increased representation in parliament “changed the definition of what is political”.

It meant that issues like childcare, rape, domestic abuse and gendered labour were no longer fringe concerns – they were increasingly mainstream politics.

More women within government ministries also meant new opportunities for women’s perspectives to be included in these spaces, long controlled by men.

One example is the transport department, which had previously overlooked the gendered impacts of its policies. As one MP told Childs, this department’s ministers hadn’t thought about building policies that benefited women because it had been “so long since they got their buggies and tried to get on a bus”.

Including more women in parliament has led to more women-focused policies – though it doesn’t always follow that women parliamentarians will always represent women’s interests – in part as “women’s interests” are so varied.

Women are diverse and may experience different, overlapping forms of discrimination based on their race, religion, disability, class, and sexuality. These realities are still underrepresented in parliament.

If women’s interests are to be truly represented in UK politics, women who are openly gay, working class, disabled, or from black and minority ethnic communities, must be encouraged to stand for election and participate.

At the same time, women MPs have historically been wary of being pigeon-holed or portrayed as representing women only. Some women MPs in the 1997 intake, for example, told Childs they had to “distance themselves from women’s issues” because those who don’t “face criticism for doing so”.

They argued that “women MPs were acting in a hostile environment, one where acting for women has accompanying costs”. Later years have seen some progress on this front – though it remains true that having a woman MP will not guarantee feminist or woman-friendly views and policies.

Having a woman MP will not guarantee feminist or woman-friendly views and policies.

The number of women MPs has continued to grow since the 1997 election, with a record of 208 elected at the 2017 election. But this is just 32% of parliament’s seats, and women are still campaigning for equal representation.

A lack of baby-friendly policies is a one example of how women are still shut out of politics. A recent scandalshowed how urgently change is needed for women to feel they can participate in parliament without being penalised for pregnancy.

This year, the Liberal Democrat MP Jo Swinson was unable to attend a key Brexit vote having just given birth. But she had entered into a “pairing” pact with an opposing Conservative MP, who agreed not to vote either, to cancel out the fact that she would be absent. Then, he went ahead and voted anyway.

Parliament depends on rules and breaking them like this suggests that MPs are prepared to play dirty to win. Now, women MPs are pushing for baby leave and proxy voting for heavily pregnant women and new mothers.

This would end one aspect of gender discrimination in parliament, making sure that all women can remain involved in decision-making without having to rely on the pairing system. This is good news; it’s a long-overdue change.

A toxic culture

Diane Abbott – UK Parliament official portraits 2017. She has received huge online abuse

Misogynistic online abuse is a further, ongoing scandal that continues to exclude women from political spaces.

Women MPs receive a disproportionate amount of this abuse, particularly BAME (Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic) women.

During the 2017 general election campaigns, the veteran Labour MP Diane Abbott, received half of all the abuse sent to women MPs online.

She warned that risks of such harassment can deter women from entering politics in the first place, and that “even the young, recklessly fearless Diane Abbott might have paused for thought”.

A recent UK government report on Intimidation In Public Life similarly warned that online abuse is limiting women’s political participation. It outlined suggested responses from political parties, the police and others. But it presented overly-modest or vague proposals on how to respond to this massive problem.

The report asked social media companies, for example, to “implement tools to tackle online intimidation through user options” and “do more to prevent users being inundated with hostile messages on their platforms”.

Women’s inclusion in politics is not inevitable.

We have come a long way since women snuck into the Houses of Parliament to watch political debates through an air vent in the loft. But we cannot afford to rest on our laurels when it comes to women’s inclusion in politics.

Polls before the 2017 election had predicted a Conservative party landslide, with Labour politicians slated to lose a significant number of seats – and women’s representation set to shrink for the first time since 2001.

This did not happen, and Labour’s better-than-expected result led to a small increase in the number of women MPs instead. But it was a near miss.

There’s a tendency to assume that progress happens in one way and one way only – that once we start to see more women or minorities included in public life, that their representation will just continue to get better and better.

In contrast, 2017 offered us a stark warning – that women’s inclusion in politics is not inevitable. It’s taken a lot of work to get us to where we are today. And it will take more work to bring more women into parliament.

* This essay was written by Sian Norris while the Ben Pimlott Writer In Residence at Birkbeck University of London.

Sian Norris is a writer and feminist activist. She is the founder and director of the Bristol Women’s Literature Festival, and runs the successful feminist blog sianandcrookedrib.blogspot.com. She has written for the Guardian, the Independent, the New Statesman. Her first novel, Greta and Boris: A Daring Rescue is published by Our Street and her short story, The Boys on the Bus, is available on the Kindle. Sian is currently working on a novel based around the life of Gertrude Stein.