How do you teach the history of war in the post-war period?

Is reconciliation impossible?

During the two-day event entitled “Clio Goes to School”, organized by the Group for Historical Education in Greece, I had the opportunity to follow the contribution of Christina Koulouri, Professor of Modern and Contemporary History at Panteion University. She presented a common educational material that aims to help the teaching of history in all Balkan countries, efforts that began when the wars in Yugoslavia had ended, a time when memories of war were very fresh, and the result was completed and published in 2016.

“We live in a time of peace, but the teaching of history revolves around wars. Some events are very remote, like the Balkan wars, but some are closer to us, like our civil war. The experience or war in all versions leaves deep scars in societies, which are transferred from generation to generation. The memory of war is the organizing principle around which many collective identities are formed. In the case of the Balkans this is even more powerful. When we speak historically of the twentieth century, we speak of wars. We start from the Balkans, we go to the First World War, then the Interwar, to the Second World War, to the Cold War, etc.”, begins the presentation by Ch. Koulouri.

About a hundred historians from different educational levels from “hostile” or rival countries sat around the same table, talked and came to a conclusion around the narrative of the common past. The result of their work has been translated into 9 languages, including Greek, and is freely available online. It contains collections of sources from all the Balkan countries, covers all chapters of common history teaching and is a handbook that can be used by teachers in any Balkan country.

“Is it possible to overcome ethnocentric narrative? How can we teach confrontational and controversial events in societies that have just experienced bloody war, genocide, massacres and displacement?” said Ms Koulouri. We usually hear that it is not possible and that we need a distance from the facts so that we can obtain the necessary tranquillity to negotiate, or that silence is preferable.

She continued: “History creates identity. This cannot be ignored or contradicted. The question is what identity it is shaping, how do we teach it to build a modern citizen. Wars are interpreted in teaching as part of an ethnocentric narrative. These ethnocentric approaches are carried out by all societies, our country is no exception. The traumatic experiences of wars stigmatize the present and create divided memories. Mainly from the side of the victims, we hear about the “duty of memory”, we must remember why we recognize the pain and traumatic experience of the victims in this way. Thus, in the public sphere, “memory wars” are being waged and there is a political abuse of the past and history by governments and parties.

The role of the school and the school manual.

“The school textbook is treated as a “gospel” which must contain the “ultimate truth”, so that its writers are also the target of attacks and criticism. The school can contribute to the reproduction of conflict if it hides the dark sides of the past and promotes a one-sided interpretation of events. There is one experience that has been discussed about the role of the school between two wars if it basically cultivated hatred toward one’s neighbour. The other aspect is whether the teaching of history can, when speaking of conflicts, contribute to reconciliation. Will we advance in reconciliation, and then will the history of teaching be reorganized? Or will we use the teaching of history to arrive at reconciliation?” asked Ms Koulouri.

Some dilemmas and the example of a common approach to the war in Yugoslavia

The first dilemma concerns the relationship between victims and perpetrators. Should the perpetrators be forgiven in order to achieve reconciliation, or is justice more important?

Should new generations learn about their past and reconcile with what their parents, grandmothers and grandfathers did?

Do we need to remember or forget the traumatic events in teaching history?

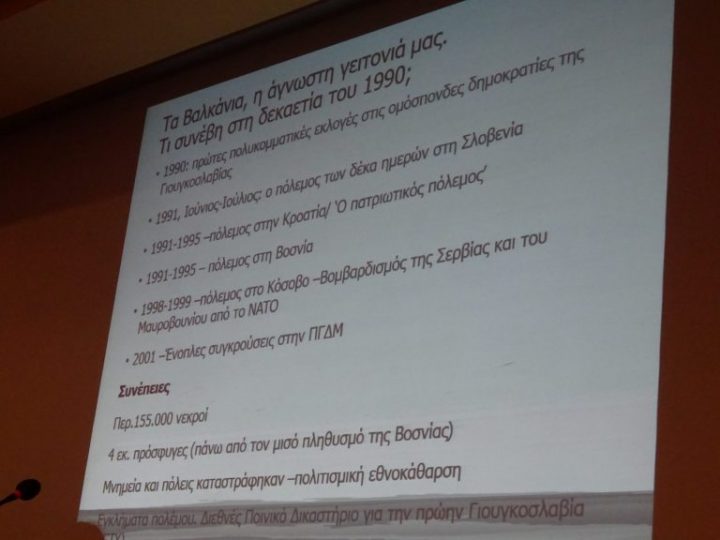

Taking the example of the war in Yugoslavia, Ch. Koulouri explained how it has been approached in the joint attempt of hundreds of historians from all the Balkan countries. On the one hand, wars, battles, the “real,” as historians call historical events. However, on the other hand, the human experience, the way in which societies experienced war, particularly children, the dark face of war, ie refugees everywhere, ethnic cleansing, the destruction of monuments and places of worship, anti-war movements of the time.

She concluded by saying: “We must incorporate the above-mentioned aspects into the hegemonic narrative of history, i.e. change the narrative about conflicts. It is a necessary strategy in historical thinking to overcome ethnocentrism and recognize diversity. With regard to memory, the choice is not between remembering or forgetting, between memory or forgetting, because forgetting is not something we can choose. The choice lies in the different ways of remembering. Reconciliation cannot be achieved either by silence or by distortions. Memory is alive, even under the veil of silence, especially when there has been a recent violent past. Education in history must undertake the difficult task of teaching about wars and conflicts to teach new generations how to deal with their dark past. “The teaching of history can be effective and convincing only when it incorporates traumatic experiences and responds to the experiences of conflict.”

Translated from Spanish by Pressenza London