What is the purpose of life? Whatever you may think is the answer, you might, from time to time at least, find your own definition unsatisfactory. After all, how can one say why any living creature is on Earth in just one simple phrase?

For me, looking back on 18 years of research into how the human brain handles language, there seems to be only one, solid, resilient thread that prevails over all others. Humanity’s purpose rests in the spectacular drive of our minds to extract meaning from the world around us.

For many scientists, this drive to find sense guides every step they take, it defines everything that they do or say. Understanding nature and constantly striving to explain its underpinning principles, rules and mechanisms is the essence of the scientist’s existence. And this can be considered the most simplified version of their life’s purpose.

But this isn’t something that just applies to the scientifically minded. When examining a healthy sample of human minds using techniques such as brain imaging and EEG, the brain’s relentless obsession with extracting meaning from everything has been found in all kinds of people regardless of status, education, or location.

Language: a meaning-filled treasure chest

Take words, for instance, those mesmerising language units that package meaning with phenomenal density. When you show a word to someone who can read it, they not only retrieve the meaning of it, but all the meanings that this person has ever seen associated with it. They also rely on the meaning of words that resemble that word, and even the meaning of nonsensical words that sound or look like it.

And then there are bilinguals, who have the particular fate of having words in different languages for arguably overlapping concepts. Speakers of more than one language automatically access translation in their native language when they encounter a word in their second language. Not only do they do this without knowing, they do it even when they have no intention of doing so.

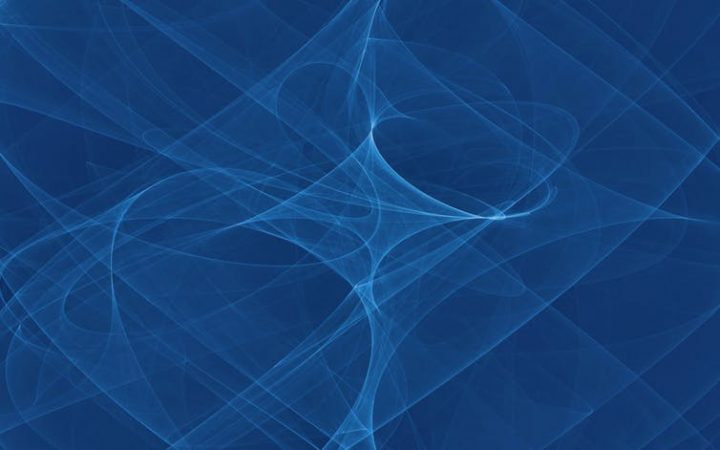

Recently, we have been able to show that even an abstract picture – one that cannot easily be taken as a depiction of a particular concept – connects to words in the mind in a way that can be predicted. It does not seem to matter how seemingly void of meaning an image, a sound, or a smell may be, the human brain will project meaning onto it. And it will do so automatically in a subconscious (albeit predictable) way, presumably because the bulk of us extract meaning in a somewhat comparable fashion, since we have many experiences of the world in common.

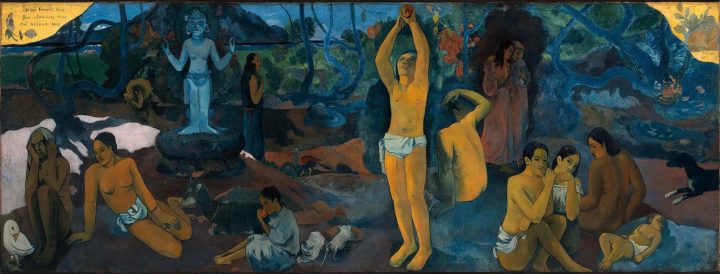

Consider the picture below, for example. It has essentially no distinctive features that could lead you to identify, let alone name, it in an instant.

Grace or violence?

Alexandru Panoiu/Flickr, CC BY-SA

You would probably struggle to accurately describe the textures and colours it is composed of, or say what it actually represents. Yet your mind would be happier to associate it with the concept of “grace” than that of “violence” – even if you are not able to explain why – before a word is handed over to you as a tool for interpretation.

Beyond words

The drive of humans to understand is not limited to just language, however. Our species appears to be guided by this profound and inexorable impulse to understand the world in every aspect of our lives. In other words, the goal of our existence ultimately seems to be achieving a full understanding of this same existence, a kind of kaleidoscopic infinity loop in which our mind is trapped, from the emergence of proto-consciousness in the womb, all the way to our deathbed.

The proposal is compatible with theoretical standpoints in quantum physics and astrophysics, under the impetus of great scientists like John Archibald Wheeler, who proposed that information is the very essence of existence (“it for bit” – perhaps the best ever attempt to account for all meaning in the universe in one simple phrase).

Information – that is atoms, molecules, cells, organisms, societies – is self-obsessed, constantly looking for meaning in the mirror, like Narcissus looking at the reflection of the self, like the molecular biologist’s DNA playing with itself under the microscope, like AI scientists trying to give robots all the features that would make them indistinguishable from themselves.

Perhaps it does not matter if you find this proposal satisfying, because getting the answer to what the purpose of life is would equate to making your life purposeless. And who would want that?![]()

Guillaume Thierry, Professor of Cognitive Neuroscience, Bangor University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.