Africa is a land of internal migration, as it has been the case for every continent on earth. The Bakongo people arrived in the region of the river Congo as part of the first Bantù migration, bringing with them the practice agriculture and iron working.

The Bakongo people were fascinated by a form of spirituality founded on the worshipping of ancestors as well as the mediators between them and humanity. The supreme deity was represented by Tata Nzambi, the creator of humanity, which he then left to its own destiny withdrawing to the skies.

According to the legend, the Bakongo were descendants of Nkaka ya Kisina. They had a matriarchal social structure and used dialogue to resolve conflicts. The Mani Kongo or Mwene Kongo, the king chosen by 12 clans, lived in the capital Mbanza Kongo. They had a currency called nzimbu, based on seashells that were used in commercial trading. The military chief was called ntinu, while the mfumu dealt with social questions.

From the XIV to the XIX century the Realm of the Congo dominated the area that corresponds to contemporary Angola and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Even though it was formally independent, it was increasingly subjected from the end of the XVI century to the influence of Portugal, which threatened its territorial integrity in order to expand its colonies.

In fact, the first European to visit the Realm of the Congo was the Portuguese explorer Diego Cão, in an event that marked a fundamental turn for all of Africa. Having arrived between 1482 and 1483 in search of slaves, he was struck by the complex organisation of the Bakongo people. During his stay in Congo, Cão kidnapped some members of the nobility and brought them to Portugal as prisoners. In 1491, when Cão brought the hostages back, king Nzinga a Nkuwu accepted to convert to Christianity and was baptised with the name of João I.

Despite the king’s protests, the Portuguese kidnapped the young to bring them as slaves to the plantations in Brazil. They also used existing divisions in the realm to accelerate its decline, creating a number of vassal realms, providing them with low-quality weapons and signing alliances with warlords to incite internal conflict.

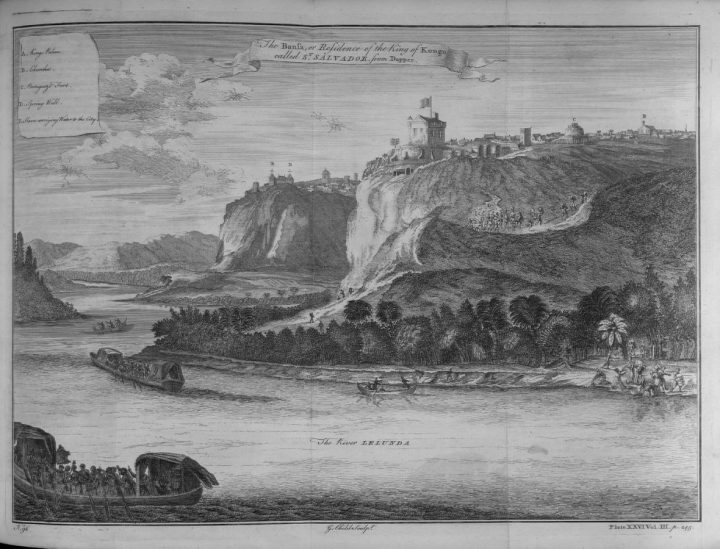

Image of the capital of the Realm of the Congo, published in 1668 by Olfred Dapper

Things changed with Nzingha Mbande, queen of Ndongo and Matamba, two realms corresponding to contemporary Angola. The daughter of king Kiluanji Ngola and his second wife Kangela, she was born in 1581 with the umbilical cord around her neck. A clairvoyant prophesied then that she would become queen – which was a real novelty at that time. From a very young age her father saw in her the characteristics of a true leader and encouraged her education in a variety of fields: he taught her horse riding and combat, stimulated her to learn Portuguese and Dutch and study the art of diplomacy and commerce.

King Kiluanji tried his whole life to resist the European invaders. At that time, the Portuguese had been opening ports for the trafficking of slaves in various parts of Africa for 100 years. When he died, he was succeeded by his son Mbande. In 1622, he nominated Nzingha as ambassador and sent her to Luanda – the current capital of Angola and, at the time, an important port for the boarding of slaves – to meet governor João Correia de Sousa and sign a peace treaty.

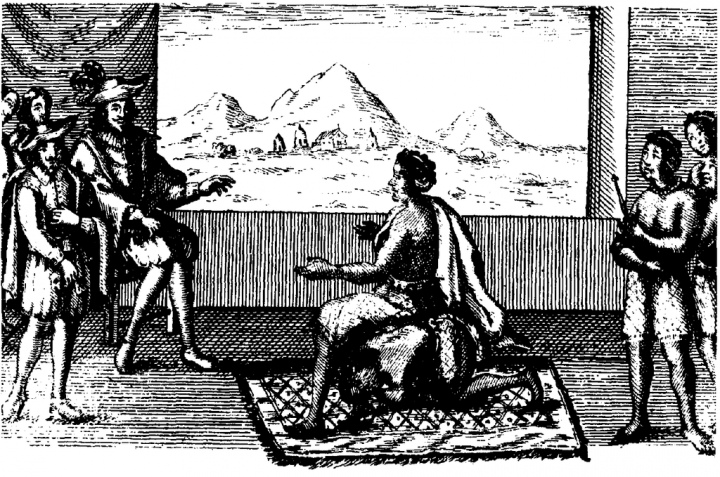

Nzingha’s real plan, however, was to chase away the Portuguese. When she arrived in Luanda, the population welcomed her with great joy. The governor, however, invited her to sit on the ground, to insult her. In order to demonstrate that she would not negotiate from a position of inferiority, Nzingha sat on the back of a servant who got down on her hands and knees. She succeeded in reaching a deal, but the terms were not respected by the Portuguese. For tactical reasons, she converted to Christianity, taking the name of Ana de Souza. After her brother’s suicide, in 1623, she became queen, aged 42, and relinquished her Christian name.

Portrait of Nzingha, François Villain, lithography

From then until her death in 1663, when she was 82, Nzingha dedicated herself to fighting the Portuguese and slavery. She offered refuge to escaping slaves and built an army which included women. She developed a new form of military organisation called kilombo, as part of which the young were separated from their families and raised in military communities. She made alliances with neighbouring people, like the Imbangala. She also allied herself with the Dutch to fight the Portuguese, but soon found out that they, too, were ready to betray the promises they had made and only wanted to enslave the people of Africa.

With her strength, dignity, pride, acumen and intransigence, Nzingha became a symbol of African resistance to European aggression and a source of inspiration for all those that would fight against colonialism and slavery.

Translation from Italian by Davide Schmid