Yuka Kobayashi, SOAS, University of London for The Conversation

China first built its famous Great Wall in the Qin dynasty during the third century BC. Never has there been a greater symbol of protectionism. But today China is outward facing to protect its national interests. It is building bridges, as well as railways, roads and infrastructure, and embedding itself at the heart of the global trade system.

The unfolding trade dispute between the US and China follows a scramble for influence by both countries to set the rules, regulations and standards for trade and investment. The crux of the US-China trade dispute lies in the declining power of the US, which is reacting to the fact that China has been catching up and closing the gap with it over the past decade.

The Trump administration’s decision to impose tariffs on China under section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974 and China’s retaliatory measures is merely the tip of the iceberg. The US-China conflict over trade is played out in various arenas as both sides battle for global influence.

Writing the trade rules

The international trade system, now governed by the World Trade Organisation (WTO), has been built on the principles of free trade. Unilateral measures, where one country targets another, run counter to these principles. The WTO has its own judicial system (the Dispute Settlement Mechanism) to mediate trade disputes: unilateral measures tend to be used as a last resort when other enforcement mechanisms in the WTO are not effective.

While the US was one of the founding members of the WTO, China joined only in 2001, after 15 years of negotiations. At the time, China had a manufacturing-based economy and was heavily reliant on trade in goods. It was neither strong in trade in services nor in the high tech sector.

But things have changed significantly, with China moving on from its transitional period in the WTO to become a fully-fledged member in 2011. The Chinese economy has moved up the economic chain, to become an economy more balanced in trade in goods and trade in services.

As its economy has developed, so too has China’s behaviour as a member of the WTO. It has become more proactive and vocal in the interpretation and enforcement of trade rules and regulations. Having been left out of the rule-making in global trade before joining the WTO, China was keen to catch up and have its interests reflected in the official body that governs world trade.

Its changing behaviour can be seen in the different approaches China took in an early WTO dispute on value added tax when it wanted to resolve things quickly, compared to the more recent automobiles case during which it was more confident and assertive, not backing down in the early stages of the dispute.

This signals the change in China’s WTO participation from being a reactive member to an active participant. These characteristics were also reflected in the Doha Round trade negotiations between WTO states, where China, together with other developing countries, became an important voice in the negotiations for trade rules, eventually leading to a deadlock when they failed to agree with the US on various issues.

Regional influence

Many countries’ frustration with the WTO’s Doha Round negotiations led to a greater focus on mega-regional trade agreements. Under the Obama administration, there were clear spheres of influence: the US-led Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and the China-led Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). These trade agreements took different approaches in intellectual property, rules and regulations, shaping the directions of trade in their different spheres.

The US position has clearly changed under the Trump administration, with the US pulling out of TPP. But China’s RCEP, which belongs under its grand strategy of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), has gained momentum. The Chinese approach to regulation and preference for looser intellectual property rules has support in developing countries, which in turn gives China more power to assert itself in the making of global trade rules.

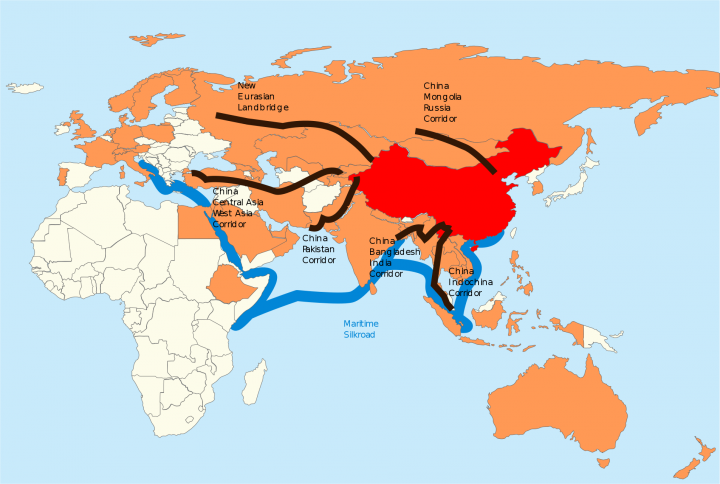

Xi Jinping proposed the BRI in 2013 to secure its trade routes across Asia and into Europe and Africa. It is part of big plans to build a strong and wealthy China, encapsulated by policies such as the “China dream” and the “two centenary goals”. As well as dealing with the country’s economic overcapacity, the BRI creates ties between China and the 76 participating countries, which allow China’s standards, rules and regulations to subtly be adopted across this network.

Moreover, the Chinese government’s “Made in China 2025” initiative aims to move the country up the economic chain from manufacturing cheap, low quality goods to more high tech ones. This goal is likely to make the US nervous, as China becomes more of a direct economic rival.

These trends of Chinese leadership in trade have been reinforced recently. Beijing announced its White Paper on the WTO and also set up two international commercial courts in Shenzhen and Xian in June, which both signal its resolve to be a leading player in global trade.

![]() So as the US builds walls of protectionism, the Chinese government is focused on building bridges with the rest of the world – through existing institutions like the WTO and also by creating its own organisations in the shape of mega-trade agreements and the BRI to further its economic interests.

So as the US builds walls of protectionism, the Chinese government is focused on building bridges with the rest of the world – through existing institutions like the WTO and also by creating its own organisations in the shape of mega-trade agreements and the BRI to further its economic interests.

Yuka Kobayashi, Lecturer (Assistant Professor) in China and International Politics, SOAS, University of London

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.