Sam Raphael, University of Westminster and Ruth Blakeley, University of Sheffield for The Conversation

The long-awaited reports of the investigation by the UK Parliament’s Intelligence and Security Committee (ISC) into Detainee Mistreatment and Rendition between 2001 and 2010 have finally been published. We ourselves have been researching the UK’s part in rendition and torture for years and gave evidence to the committee – and these reports are much harder hitting than we had expected.

Chaired by MP and QC Dominic Grieve, the ISC’s investigation has revealed that the extent of UK involvement in prisoner abuse was even greater than we had previously documented. The reports also highlight serious weaknesses relating to the training of security personnel, and governance and oversight of their conduct. Many of the ISC’s conclusions corroborate our own research findings, and we were pleased to see a number of issues we raised when we gave evidence to the ISC in January 2017.

As we have argued for years now – and as we told the ISC – British complicity in torture was deep, wide and sustained. Government ministers have always denied this – the former foreign secretary, Jack Straw famously stated that only conspiracy theorists should believe the UK was involved in rendition. That position is now more untenable than ever. It is clear from the ISC reports that UK officials knew about the US programme immediately after 9/11 and worked to support their allies in ways which enabled continued “plausible deniability”.

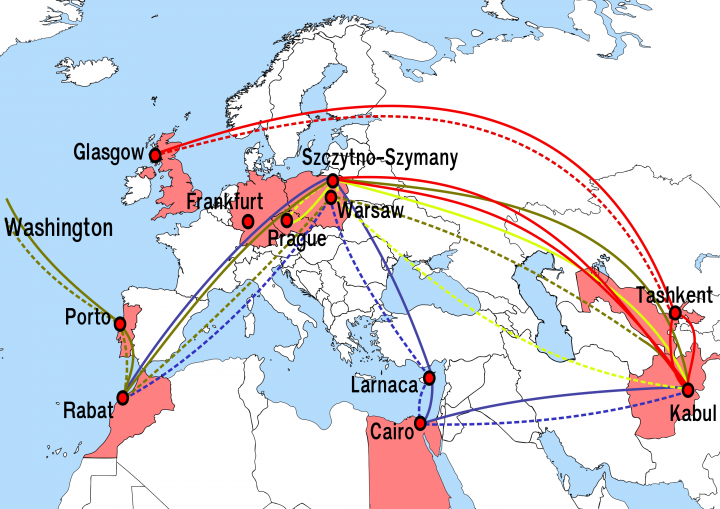

The report’s findings are unambiguous. In more than 70 cases – far more than have ever been identified before now – British intelligence knew of, suggested, planned, agreed to, or paid for others to conduct rendition operations. Some of the details are excruciating – one MI6 officer was present while a prisoner was transferred in a coffin-sized box. In literally hundreds of further cases, UK officials were aware of detainees being mistreated by their allies, continued to supply questions to be asked of detainees under torture, and received intelligence from those who had been tortured.

While names and locations have been redacted in these reports, our own years of investigation enable us to fit new facts into our broader picture of post-9/11 torture. It is likely that we will be able to identify some of the important detail left out by the reports. In many cases, these omissions resulted from the government refusing to allow the ISC to interview intelligence officers with knowledge of British involvement. In the absence of a full judge-led inquiry, our fact-finding work remains crucial, and we are committed to doing what we can.

We also know enough from the victims themselves, in their own words, about the human toll of this form of state violence. If you are being beaten up, electrocuted, raped, or subjected to mock execution, you tend to say whatever it takes to make it stop. Small wonder that intelligence received under torture is notoriously of limited value.

The fact that the UK attempted to keep its hands clean by involvement from afar makes the situation no better. When the reports were released, Theresa May stated that “intelligence and Armed Forces personnel are now much better placed” to deal with detainee-related work and that the necessary lessons have been learned. But in our evidence to the ISC, we also raised a number of concerns about the adequacy of today’s training and the strength of current guidance, which ostensibly prevents a return to the early years of the “War on Terror” – and we are not convinced.

No stone unturned

In our testimony to the ISC, we pointed to flaws in the so-called “Consolidated Guidance” issued to all security agencies and the military from 2010. The ISC has taken this seriously. In their conclusions, it concludes that the guidance is by no means “consolidated”, and that “it is misleading to present it as such”. The ISC points to “dangerous ambiguities in the guidance”, noting that “individual ministers have entirely different understandings of what they can and cannot, and would and would not, authorise”.

We encouraged the ISC to examine how frequently agency or Ministry of Defence personnel had followed the guidance, and to establish how frequently concerns about prisoner abuse were reported up the chain of command. This the ISC has done. Frustratingly, corresponding data is redacted from the final release. Nevertheless, the ISC’s conclusions indicate that record keeping on these matters is weak, and that there are considerable risks that cases which should be reported upwards are not.

This is exacerbated by the fact that “there is no clear policy and not even agreement as to who has responsibility for preventing UK complicity in unlawful rendition”. And as the ISC reports, the government “has failed to introduce any policy or process that will ensure that allies will not use UK territory for rendition purposes”.

We have long argued that the Consolidated Guidance does little more than provide a rhetorical, legal and policy scaffold, enabling the UK government to demonstrate a minimum procedural adherence to human rights commitments. As the ISC quite rightly concludes, there is an urgent need for review and fundamental reform of the Consolidated Guidance. The government must also establish much more robust oversight, training and accountability mechanisms.

![]() We would also argue, in the strongest possible terms, that only a judge-led inquiry with full powers of subpoena will enable the public to know what was done in their name. Without this it will be even harder to achieve full accountability and to identify current forms of UK complicity in human rights abuses. With the anti-torture norm being eroded at the very top of the US government once again, these risks are very present and real.

We would also argue, in the strongest possible terms, that only a judge-led inquiry with full powers of subpoena will enable the public to know what was done in their name. Without this it will be even harder to achieve full accountability and to identify current forms of UK complicity in human rights abuses. With the anti-torture norm being eroded at the very top of the US government once again, these risks are very present and real.

Sam Raphael, Senior Lecturer in International Relations, University of Westminster and Ruth Blakeley, Professor of Politics and International Relations, University of Sheffield

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.