Skin lightening is a longstanding practice that occurs in many parts of the world. It’s been done through the use of creams, lotions, soaps, folk remedies, and staying out of the sun. The desire for light skin has been extended to children too. Advice to “marry light” is not uncommon in Asian and black families, for example, in order to produce a light-skinned child.

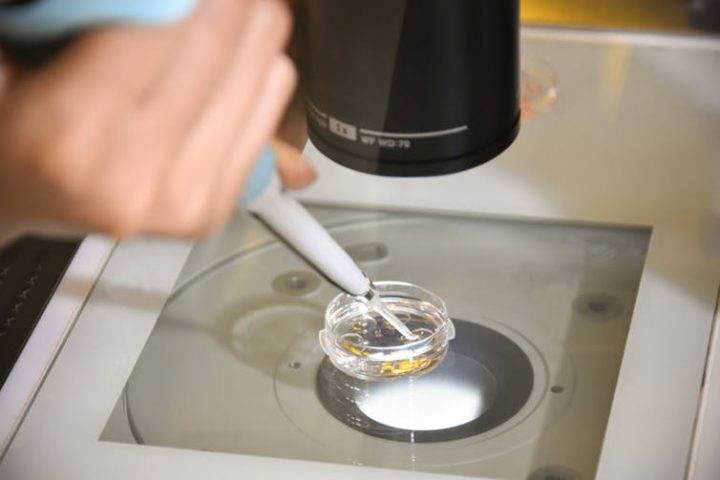

Some have also tried to lighten the skin of their unborn child with the help of new technologies, whether or not these technologies are effective or safe. In Ghana, some women have reportedly taken a pill to lighten the skin of their foetus despite the questionable science. Others in the US using IVF technology have selected egg or sperm donors with light or white skin irrespective of the inaccurate results. There is even the possibility – however remote at the moment – of genetic selection of embryos for traits such as fair skin. If there was a diagnostic test for skin tone that could be carried out on embryos, for instance, reproducers could select “this” embryo likely to have fairer skin over “that” one likely to have darker skin.

Philosophers have offered some conflicting moral principles to provide direction on whether people looking to have a child via assisted conception technologies should select certain embryos. While some have suggested that we should not select at all, others have argued we should select embryos in various morally significant ways. These include picking: the “best” child; the child you most want; the child that will do the least harm to others; or the child that will provide the most benefit to others.

Complicity of companies and states

Whatever the current plausibility of these various interventions, I believe there is a wider socio-political question to ask in these debates. This goes beyond individual decisions, and looks at the role played by companies which provide embryo, or sperm or egg, selection services, or skin-lightening products, and those legislators who govern such practices.

Companies that produce skin-lightening pills for foetuses, laboratories that develop technology for non-disease embryonic selection, and clinics that offer sperm and eggs likely to have lighter skin at a higher cost, all have a vested, monetary, interest in offering these services or products.

Liberal democracies too might want to allow such services or products because decisions about children are private matters and such states profess to respect citizens’ autonomy. Non-liberal democracies might want populations that are stronger, smarter, more competitive or more beautiful.

The hypothetical argument is that, so long as there are protections in place – it is medically safe, no one is coerced, and there is recourse to resolve disputes – then it should be permitted.

Shutterstock

Some moral arguments about selection

However, there are moral arguments – most often raised in the case of disability, but no less relevant in other cases – against these practices. Foremost among them is a concern over being eugenic if we select against disability. Applying this to the skin colour case, if babies are bred to have fairer skin, could whole populations of darker skinned people begin to disappear?

Defenders of non-disabled embryo selection reject this eugenic concern. They argue this is because neither the state, at least in liberal democracies, nor companies, are mandating the selection of particular traits. Rather it is individuals who are choosing what they want. This could apply equally to the skin colour case too.

There are other concerns too when selecting against disability, including what is expressed about current disabled people through selection. When applying this to the skin colour case, if darker skin is chosen less often by parents than fairer skin – a global trend when buying sperm and eggs for IVF for surrogacy – then existing darker skinned people might feel they are less valuable.

Those philosophers that defend embryo selection against disability discount this worry by proposing ways to make current disabled people feel valuable. By extension, others may argue that although people could select against darker skin, we can promote broader messages that emphasise that dark skin is beautiful and that existing darker-skinned people are valuable.

Colourism is a practice where one type of skin colour is portrayed as better than another.

Colourism is a practice where one type of skin colour is portrayed as better than another.

Colourism

Another worry that I am exploring in my research, is that companies or states that offer or allow embryo selection for fairer skin are complicit in practices that are substantively about one type of skin colour being better than another – a form of what’s called “colourism”. Put into a context where skin colour, as a proxy for race and ethnicity, has been used to enslave, colonise, rape and marginalise, this is deeply troubling and ethically suspect. If we are committed to values of equality, where skin colour – among other traits – should not matter to us privately or publicly, it’s wrong to allow companies and institutions to develop or permit selection for this very unequal thing.

![]() Banning practices can drive them underground: the pill to lighten foetuses is illegal, as is mercury in products, which also lightens skin. Yet both are still available, and are used by some of the poorest women in the world to boot. Stopping production of such products or services won’t eradicate the desire or societal norm in some places for lighter skin. But companies and states should consider whether current products – like lightening creams – or future interventions, such as embryo selection for fair skin, encourage or perpetuate inequality, and they should not partake in them if they do.

Banning practices can drive them underground: the pill to lighten foetuses is illegal, as is mercury in products, which also lightens skin. Yet both are still available, and are used by some of the poorest women in the world to boot. Stopping production of such products or services won’t eradicate the desire or societal norm in some places for lighter skin. But companies and states should consider whether current products – like lightening creams – or future interventions, such as embryo selection for fair skin, encourage or perpetuate inequality, and they should not partake in them if they do.

Herjeet Marway, Lecturer in Global Ethics, Department of Philosophy, University of Birmingham

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.