We speak to world-renowned Indian author and activist Arundhati Roy about the increasing incidence of rape in India, as police there say they have arrested the main suspect in an alleged gang rape and murder of a teenage girl. Dhanu Bhuiyan and his accomplices are accused of burning the 16-year-old girl alive on Friday. She was reportedly murdered in the eastern state of Jharkhand after her parents complained to the local village council that she had been raped. The council told accused rapist Dhanu Bhuiyan to do 100 sit-ups and pay a 50,000 rupee fine—that’s $750—as punishment. The men were allegedly so enraged by the penalty that they beat the girl’s parents, then set her on fire. The attack is just one of the most recent of a series of brutal incidents of sexual violence against minors. Meanwhile, there were 40,000 rapes reported in India in 2016, and 40 percent of the cases involved child victims.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: We end today’s show in India, where police say they’ve arrested the main suspect in an alleged gang rape and murder of a teenage girl. Dhanu Bhuiyan and his accomplices are accused of burning to death the 16-year-old girl on Friday. He’s one of 15 people who have been arrested in connection with the murder. She was reportedly murdered in the eastern state of Jharkhand after her parents complained to the local village council she had been raped. The council told the accused rapist to do 100 sit-ups and pay a 50,000 rupee fine—that’s $750—as punishment. The men were allegedly so enraged by the penalty, they beat the girl’s parents and set her on fire. This is the girl’s sister speaking on Indian television Saturday.

VICTIM’S SISTER: [translated] The boy was asked to pay 50,000 rupees by the panchayats. He said he would pay 30,000 rupees, and later he said he won’t pay any money. He said he won’t marry my sister. Then all the fighting started.

AMY GOODMAN: The Jharkand attack is one of the most recent of a series of brutal attacks of sexual violence against children. Protests erupted last month over the gang rape of an 8-year-old Muslim girl in a Hindu-dominated area of the state of Jammu in Kashmir. One of the three suspected rapists is a police officer. Authorities say the motivation for the kidnapping, rape and murder of the girl, named Asifa Bano, was to drive her Muslim family out of their village. Two lawmakers with the ruling BJP party in India were forced to resign, after they helped organize rallies in support of the accused rapists, sparking widespread outcry.

Last month, India’s Cabinet approved the death penalty for rapists of girls below the age of 12 after the prime minister, Modi, held an emergency meeting in response to nationwide outrage in the wake of the rape cases. According to government officials, the order also amends the law to include more drastic punishment for a convicted rapist of girls below the age of 16. This comes as there were 40,000 rapes reported in 2016, 40 percent of them child victims.

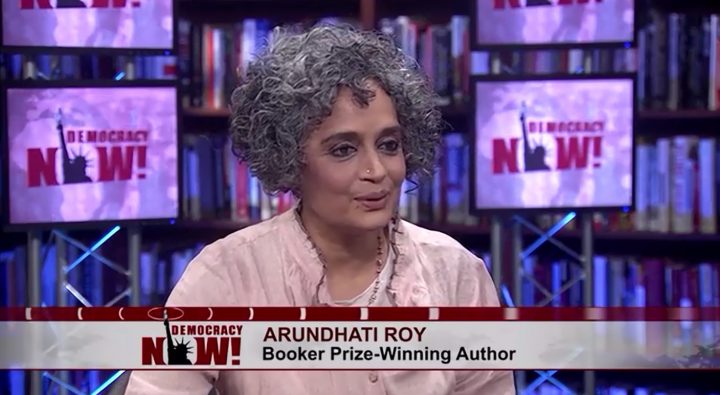

Well, last week, Nermeen Shaikh and I spoke to the world-renowned Indian author and activist Arundhati Roy in our studio about the increasing incidence of rape in India.

ARUNDHATI ROY: It’s not that Modi had an emergency meeting and called for the death penalty because he was concerned about the protests and so on. What happened was that he did not respond when the rape actually happened, when the protests began. It’s only after he went to England and realized it was a big issue internationally, and, again, had to make a spectacle, an appearance of doing something. But the truth is, first of all, I’m against death penalty, you know—the death penalty. But what actually happens is, of course there’s a death penalty for mass murder. All the people who were involved in mass murder in Gujarat were sentenced to death, very dramatically, and then released. You know? So, really, it’s a question of gathering evidence, of making a really strong case, of taking—of doing things because you really want to do them, not because you want to perform on some international stage by making these empty declarations, you know?

So, the trouble is that, you know, you have rapes, you have these brutal men who are raping women. Of course Hindus are raping girls, Muslims are raping girls, everybody’s raping girls, and so there’s no question of it belonging to only one community. But what is new over here is that, aside from the fact that the girl was not just raped and killed, she was held in a temple—according to the police reports, held in a temple, drugged, raped and then bludgeoned to death. There’s a sort of ritualistic, Satanistic part to it, which is terrifying, you know. But leaving aside the criminals, the fact that people are marching in support of the rapists—men and women, you know, are marching in support of the rapists, marching, demanding the charges be withdrawn. This is what is frightening.

I mean, in the course of one year, there was a godman called Ram Rahim who was sentenced to—convicted of rape. His supporters created havoc. You know, this rape, the Hindu Ekta Manch, the Hindu Unity Manch, is marching in support of rapists. Asaram Bapu, another godman—both these godmen very close to Modi—convicted of rape. They had to have a security lockdown in three states, because the people who are going to support the rapists are going to create trouble. So, this is something we’ve got to wrap our heads around, you know? It’s gone beyond just the little girl that was raped and the maniacs who raped her.

But the politicization of this, you know, what is it? What is going on? After all, we are in a society where it has been allowed for upper-caste men to rape Dalit women. It is their right, seen as their right. You know, we live in places like where—places like Manipal, Nagaland and Kashmir, army’s officers and soldiers who have been accused of rape are protected by the Armed Forces Special Powers Act, you know? So, it is a bit naive to say, “You know, let’s not politicize it.” But it is political. It is political. And it has to be looked at in that way.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Well, I mean, sexual violence against girls and women has reportedly increased since Modi came to power in 2014. So, could you, you know, elaborate on that? I mean, you’ve given some indication now, but do you think that, under his administration, there is somehow a more permissive attitude towards this kind of sexual—

ARUNDHATI ROY: There’s a more permissive attitude to all forms of violence. Right? People know that they will be protected in the end. I mean, rape, yes, but lynching, too, hacking someone to death because they suspected of eating beef, hacked—flogging somebody because they are—flogging Dalits because they are transporting dead cattle. You know, every kind of violence is being support. Often the victims have cases filed against them.

So, as long as the perpetrators belong loosely to this Hindu family, as they call it—the Hindutva family, rather—they know that even if they go in for a few days to jail, when they come out they will be greeted as heroes. And as we come up to the elections, you’re seeing a situation where, for example, just two days ago in Gurgaon—this is just outside of Delhi—a group of thugs went and prevented Muslims from saying the namaz outdoors.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Prayers.

ARUNDHATI ROY: Right. And then they were arrested for a few days. There was huge protests asking for them to be released. Then they gave a decree saying that, “From now on, we will decide where Muslims are allowed to pray. They cannot pray outside, unless it’s more than 50 percent of the local population. But we’ll decide.” And it’s being allowed. And all these burners are being turned up, because now, given the fact that demonetization and the new goods-and-services tax has broken the back of all small enterprises and local people, the only way that they’re going to drum up support is through polarization.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s world-renowned Indian author and activist Arundhati Roy. Her second novel has just come out in paperback, The Ministry of Utmost Happiness. Her first novel is The God of Small Things. You can watch our full interview on our website at democracynow.org.