Vincenzo Bove, University of Warwick for The Conversation

UK arms exports to Saudi Arabia increased by 175% in the first nine months of 2017 according to an investigation by the Campaign Against Arms Trade. Similarly, France and the US are major exporters of arms to the oil-rich Gulf state – in 2017 alone, they were worth around US$2.6 billion.

Selling weapons is a lucrative business. As well as the money to be made, the arms trade is also a barometer of the quality of relationships between states and it creates an interdependence that gives current and future recipient governments incentives to cooperate with arms suppliers.

Oil dependency is another reason. Sometimes this idea is disregarded as a conspiracy theory, but colleagues Claudio Deiana, Roberto Nisticò and I recently researched the extent to which oil-dependent countries transfer arms to oil-rich countries. It turns out it’s a lot.

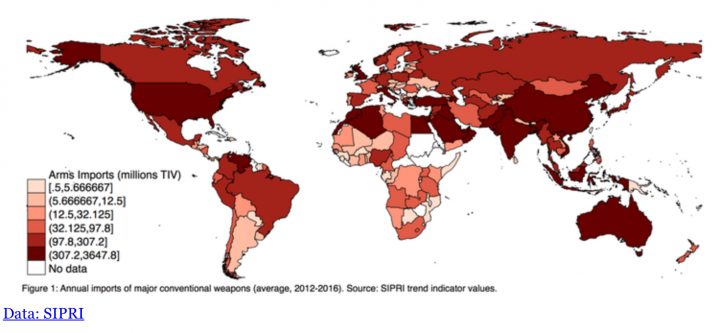

The international transfer of weapons is one of the most dynamic and lucrative sectors of international trade. By one estimate, from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, global transfers of major weapons have grown continuously since 2004 and between 2012 and 2016 reached its highest volume for any five-year period since the end of the Cold War. The value of the global arms trade in 2015 was at least US$91.3 billion, roughly equal to the GDP of Ukraine, or half of Greece’s GDP.

Since no country is self-sufficient in arms production – even the US – most of the countries in the world import weapons. This is shown in the image below, which displays the volume of arms imports of major conventional weapons between 2012 and 2016.

At the same time, the export of arms is a key part of national policy – and weapons are often given only to close allies. It is not unusual to observe arms transferred for free to allies, under the umbrella of military aid, such as US military support to Colombia to fight drug cartels and insurgent groups. Equally, the absence of trade in arms between two countries can reflect a desire to safeguard national security. For example, if there are fears that the importing nation can become a future threat.

The oil connection

To test the idea that energy dependence leads to a higher volume of arms transfers between countries, we assembled a large dataset with information on oil wealth (such as production, reserves and recent discoveries) and oil trade data, to measure energy interdependence and the potential damage of regional instabilities to oil supplies.

We found the existence of a “local oil dependence”, which indicates that the amount of arms imported has a direct relationship with the amount of oil exported to the arms supplier. Speculatively, arms export to a specific country is affected by the degree of dependence on its supply of oil. The larger the amount of oil that country A imports from country B, the larger will be the volume of arms that country A will transfer to country B.

But we did not only find the existence of a direct oil-for-weapons relationship. Our results also reveal the presence of a “global oil dependence”. The more a country depends on oil imports, the higher the incentives are to export weapons to oil-rich economies, even in the absence of a direct bilateral oil-for-weapons exchange. The idea is that by providing weapons, the oil-dependent country seeks to contain the risk of instabilities in an oil-rich country.

The oil-rich country does not necessarily need to be the oil-dependent’s direct supplier, however, because disruptions in the production of oil are likely to affect oil prices worldwide. Violent events such as civil wars or terrorist incidents are often accompanied by surging oil prices, or more general insecurity in the supply of oil. This was the case in many recent wars, such as the Gulf War and the Iraq War, the political unrest in Venezuela in 2003, and the recent Iraq-Kurdistan conflict.

So it does not matter how much oil the UK directly imports from Saudi Arabia for it to want the country to remain stable, which in turn keeps oil prices stable. In line with this, we found that a country with a recent discovery of new oil fields will increase its import of weapons from oil-dependent economies by 56%.

![]() Our results point consistently toward the conclusion that the arms trade is an effective foreign policy tool to secure and maintain access to oil. As such, the arms trade reveals national interests beyond simple economic considerations and the volume of bilateral arms transfers can be used as a barometer of political relations between the supplier and the recipient states. At the same time, we find that oil might play an even larger role in influencing economic and political decisions than is generally acknowledged.

Our results point consistently toward the conclusion that the arms trade is an effective foreign policy tool to secure and maintain access to oil. As such, the arms trade reveals national interests beyond simple economic considerations and the volume of bilateral arms transfers can be used as a barometer of political relations between the supplier and the recipient states. At the same time, we find that oil might play an even larger role in influencing economic and political decisions than is generally acknowledged.

Vincenzo Bove, Reader in Politics and Quantitative Methods, University of Warwick

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.