By

European austerity is a politics of power. It’s a banker protection racket. And the fact is, the strategy has now failed.

We hear much talk today of how we need a “more balanced, principled discussion” on trade. Such a discussion would begin by acknowledging the historical significance of Alexander Hamilton, Friedrich List, Henry Carey, the ‘American System’ and the fact that every successful modern industrial society was actually protectionist until it no longer needed to be, including the UK which had Imperial Preference.

US global strategy today is to dominate resources and finance – teaching how to do this and training caciques are major functions of this university, as I’ve known since Baby Somoza, as we called him, was my Quincy House-mate back in 1972.

Let’s not kid ourselves:

- – Free Trade is the doctrine of the dominant

- – The Gold Standard was the doctrine of the rich

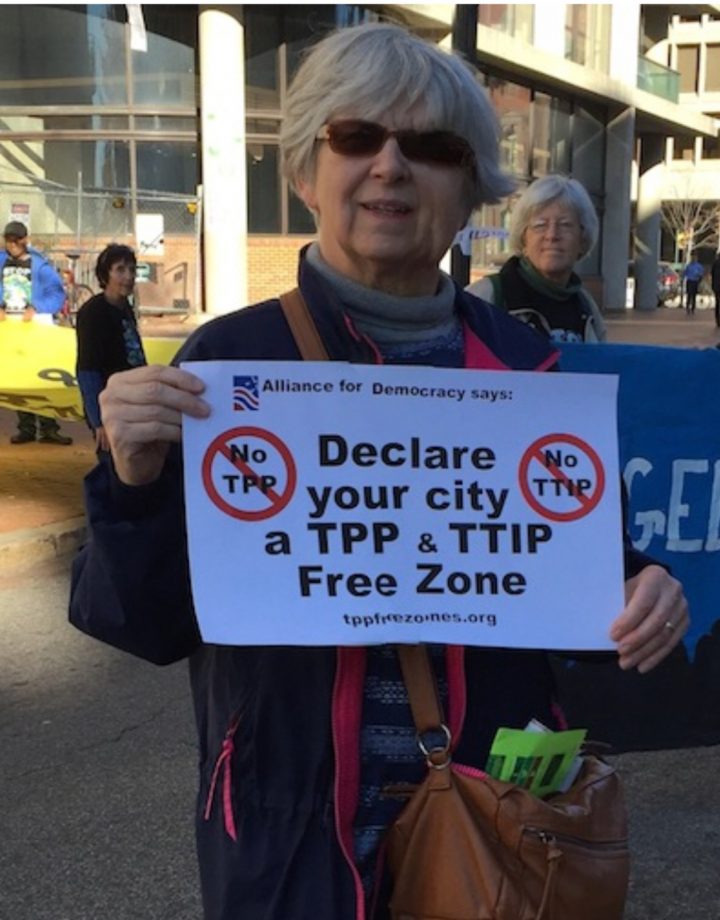

- – TPP was aimed at China

- – TTIP was economic NATO

- – The NAFTA was a bailout pact

Let me turn to an area on which I claim the authority of having worked hand-in-glove for five months with the finance minister of the country in question, and that is the treatment here of the case of Greece. Dani Rodrik’s argument is that ‘structural reforms’ imposed on Greece will work in good time if implemented with zeal and persistence. Thus privatization will lead to the ‘rationalization of production…’ and so forth. Greece has wiped out trade unions – and now has a wholly deregulated labour market with no jobs to show for it – but don’t worry, “the bulk of the benefits come much later.” Let the beatings continue until morale improves!

How the logic of rationalization applies to public beaches is not clear. Or even to airports, when the Germans seized the profitable ones but left the unprofitable ones to the Greeks. In the public sector, 300,000 dismissals led to hospitals I was warned not to patronize, or “you’ll leave in a box.” The benefits… will come later? The benefits… will come later?

The truth of Greece is that ‘structural reform’ is a sham. Austerity policy is an open-handed asset grab. It was not intended to bring recovery to Greece but to quell resistance elsewhere, a point directly acknowledged by the German Finance Minister, Wolfgang Schäuble, and reported by Yanis Varoufakis in his memoir. And the Greeks understood. Their refusal of terms was not emotional or irrational. I was in the vast crowds in Syntagma Square two nights before the July 2015 referendum and the mood was calm, brave and grimly determined.

You cannot understand European austerity as a matter of good reforms that haven’t yet borne fruit. Nor were they good-faith reforms that, unfortunately, did not work out. European austerity is a politics of power. It’s a banker protection racket. And the fact is, the strategy has now failed. First in Britain, and now in Italy, a consequential country mentioned here only in passing, just once, in a list. But the Italian pot has been simmering for years. And the voters in Italy, however much one may stereotype and disparage them, know exactly what they just did. The voters in Italy, however much one may stereotype and disparage them, know exactly what they just did.

A final point concerns the long argument over rising inequality. Is it trade? Or is it technology? Or is it both, and in which combinations? This debate has been going on for a quarter century – I published my first book on it in 1998 – but the research has long been overtaken by evidence developed since then, which clearly shows a global macroeconomic pattern to the movement of inequality, driven by changing financial regimes, debt crises, the collapse of the East bloc, commodities busts, and in many countries by the movement of exchange rates, driven by financial speculation.

The notion that it takes a trade flow – a movement of quantities – to affect a matrix of relative wages is a debilitating textbook reflex of economists. A large relative-price shock, such as an exchange crisis, is much more efficient. Neither trade volumes nor technologies in use need to change. As an economist from Chicago put it, how many companies do you need for a competitive price? The answer is: one and the threat of entry. This is the same principle, writ large.

The above is an extract from the author’s remarks at a conference on ‘Rethinking Trade and Investment Law, Harvard Law School, April 14, 2018, published on DiEM25.