Kalwant Bhopal, University of Birmingham for The Conversation

Racism is truly alive and kicking in British society, not least in liberal, progressive universities. This was evident in early March when a black female student released a video of people shouting “we hate the blacks” outside her room in her halls of residence. Unfortunately, this incident is far from isolated.

In my new book, I examine how race and racism continue to disadvantage those from black and minority ethnic backgrounds both in universities and wider society. By virtue of their racial identity, such groups are positioned as outsiders in a society which values and privileges whiteness.

In Britain, policies that attempt to be inclusive actually portray an image of a post-racial society, in which racial inequalities and racism no longer exist. In reality vast inequalities between white, black and minority ethnic communities continue to exist. They exist in the access to the labour market, in schools – and in higher education.

Bastions of whiteness

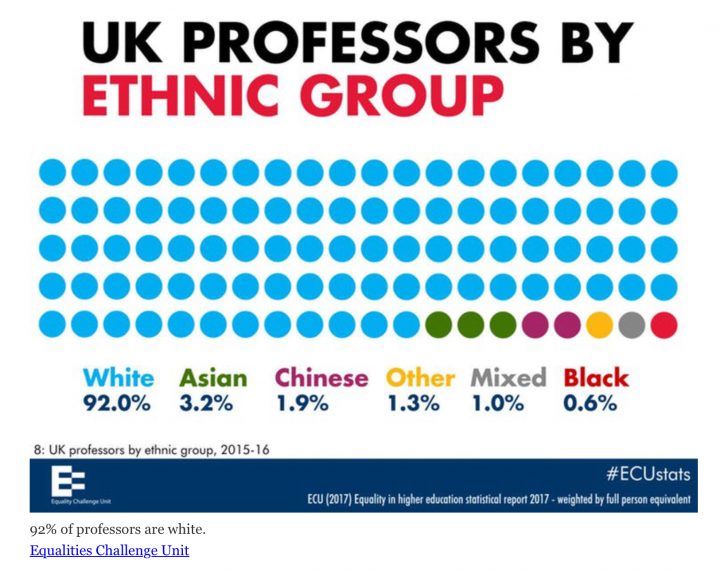

On the one hand, universities position themselves as bastions of equality and diversity, liberal in their outlook and at the forefront of instigating change in their contributions to knowledge and adding to the experiences of students. Yet, on the other hand, they fail to represent the ethnic diversity of the student body, with the vast majority of the most senior positions occupied by white people. And they continue to be dominated by those from white, middle-class backgrounds.

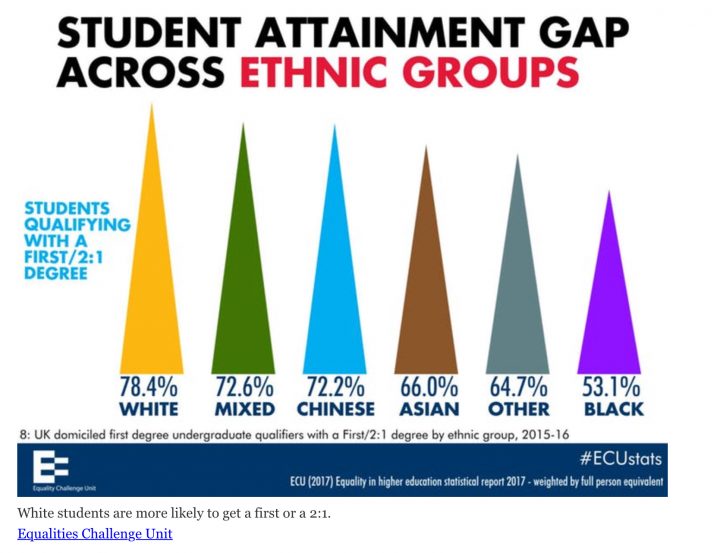

Recent evidence from the Equality Challenge Unit, which works to further equality and diversity for staff and students at UK universities, suggests that black, minority ethnic staff are under-represented in the highest contract levels and over-represented in the lowest, making up only 1.6% of heads of institutions and only 2.9% working as senior managers and directors. There are only 80 black professors in the UK compared to 13,295 who are white – or 0.6%.

A 2016 survey conducted by the Universities College Union found that 72% of black academics reported having experienced some form of bullying and harassment from colleagues. They also found themselves excluded from decision making by being a token person on committees and subject to cultural insensitivity.

Not treated as racism

In research for my book among people who work in higher education, I’ve found that racist behaviour manifests itself in subtle, nuanced and covert ways and is sometimes dismissed and ignored by senior managers who fail to take it seriously. One woman I interviewed experienced subtle micro-agressions such as not being addressed in meetings, not being given eye contact or asked for her opinion. She also witnessed derogatory remarks made in public about minority ethnic groups from the person who she alleged was racially bullying her.

When complaints of racism are made, I’ve been told of instances where they weren’t treated as racist. The acceptance of such covert racism undermines the position of the victim and questions whether such behaviour is genuine. This perpetuates white privilege in which mechanisms are used to ensure that those from black and minority ethnic backgrounds are positioned as outsiders in the white space of the academy.

I’ve heard about some senior managers in universities who were reluctant to recognise or address racism, refusing to accept it can take place in the corridors of the liberal academy. One person I interviewed spoke of negative and derogatory comments that were made to her and about other minority ethnic groups. She complained to her manager who said it was probably a “clash of personalities” rather than racism.

The idea that racism could not take place in higher education is related to a refusal to accept its existence. And it reinforces the protection of white identities which mask covert acts of racism. If a senior manager refuses to accept such behaviour as racism, they are in fact dismissing such behaviour and discouraging others from complaining about racism. Given that senior management roles are occupied by white people, this behaviour works to reinforce and privilege whiteness. This process allows white people to actively protect and perpetuate their own position of privilege and the whiteness of institutions.

Exacerbating inequalities

Some policies designed to address these issues have in fact exacerbated rather than addressed inequalities. On the face of it, policy making on inclusion in higher education paints a positive picture of equity. Most universities have specific policies on equity and inclusion. And, bearing in mind that universities, just like other organisations, are legally bound to comply with the 2010 Equality Act, this should be relatively simple to deliver.

The most important development of the Equality Act was its inclusion of “protected characteristics” – one of which is race. It placed a general duty on schools and higher education institutions to have due regard to eliminate discrimination, harassment and victimisation to advance equality of opportunity and foster good relations.

But in its attempts to protect individuals from racism and discrimination, the Equality Act has actually marginalised the very people it was designed to help. The law brought together all previous legislation into one single act to provide a legal framework to protect people’s equal rights. Before this, individual legislation such as the Race Relations Amendment Act focused on race. This has now been amalgamated with other legislation under the Equality Act. In doing so, the attention given to racial inequalities has been eroded.

![]() Within the culture of higher education, this means that white privilege is often protected and whiteness is reinforced in a way that can fail to acknowledge racism. Until higher education institutions wake up to this realisation, black and minority ethnic groups will be continue to experience racism whether it’s in halls of residence or the corridors of academic institutions.

Within the culture of higher education, this means that white privilege is often protected and whiteness is reinforced in a way that can fail to acknowledge racism. Until higher education institutions wake up to this realisation, black and minority ethnic groups will be continue to experience racism whether it’s in halls of residence or the corridors of academic institutions.

Kalwant Bhopal, Professor of Education and Social Justice, University of Birmingham

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.