Buried in a company announcement was acknowledgement that nearly all of its users have been targeted to some degree

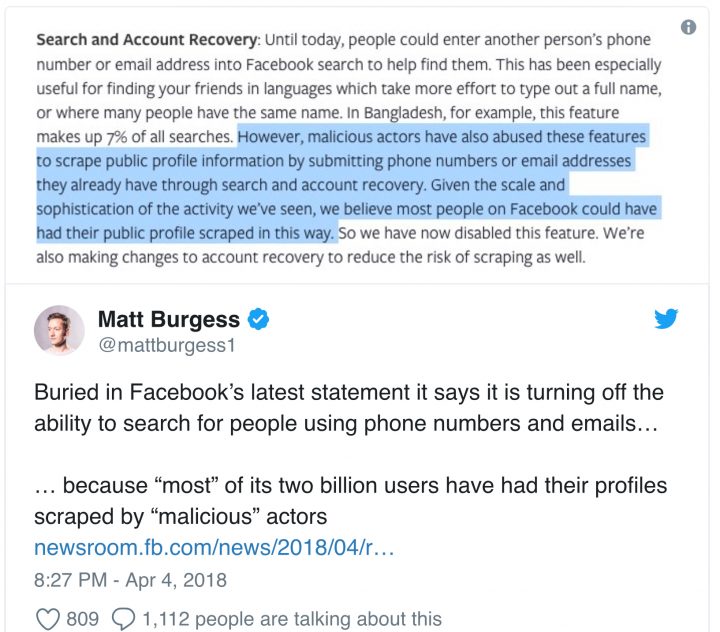

“Buried in Facebook’s announcement that Cambridge Analytica had improperly gathered data from up to 87 million users—rather than the previously reported 50 million—was the stunning admission that “malicious actors” exploited the social networking site’s search features to collection information from “most” of its 2 billion users.The detail was pointed out on Twitter by Wired journalist Matt Burgess, among others:

Until today, people could enter another person’s phone number or email address into Facebook search to help find them,” Facebook’s chief technology officer Mike Schroepfer wrote in a company blog post on Wednesday. “Given the scale and sophistication of the activity we’ve seen, we believe most people on Facebook could have had their public profile scraped in this way. So we have now disabled this feature.”

In other words, Facebook leadership believes that over the course of several years, these “malicious actors” utilized the now-disabled search features to collect whatever personal information that most of its users had sometimes unknowlingly set to “public.”

As the Washington Post explained:

[M]alicious hackers harvested email addresses and phone numbers on the so-called “Dark Web,” where criminals post information stolen from data breaches over the years. Then the hackers used automated computer programs to feed the numbers and addresses into Facebook’s “search” box, allowing them to discover the full names of people affiliated with the phone numbers or addresses, along with whatever Facebook profile information they chose to make public, often including their profile photos and hometown.

…Facebook users could have blocked this search function, which was turned on by default, by tweaking their settings to restrict finding their identities by using phone numbers or email addresses. But research has consistently shown that users of online platforms rarely adjust default privacy settings and often fail to understand what information they are sharing.

Hackers also abused Facebook’s account recovery function, by pretending to be legitimate users who had forgotten account details. Facebook’s recovery system served up names, profile pictures and links to the public profiles themselves. This tool could also be blocked in privacy settings.

“We didn’t take a broad enough view of what our responsibility was and that was a huge mistake. It was my mistake,” Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg said on a conference call with reporters on Wednesday.

This admission comes as Facebook faces heightened scrutiny over the Cambridge Analytical scandal, which has raised widespread concerns about digital privacy. In what had been called the social media company’s “largest-ever data breach,” a series of investigative reports last month revealed that Cambridge Analytica—a political consultancy data firm hired by then-candidate Donald Trump and other GOP politicians—exploited Facebook to secretly harvest personal information from millions of Americans.

In response, digital advocacy groups have demanded that Facebook leadership immediately notify users whether their data was collected by the firm, and the Federal Trade Commission has launched a probe of the company, which expanded public awareness of the issue and caused some users to realize for the first time the “creepy” reach of Facebook’s data collection.

“This is a crisis of trust. Mark Zuckerberg needs to demonstrate that Facebook users’ wellbeing—not Facebook’s profit line—is the company’s number one priority,” Kurt Walters, campaign director at Demand Progress, said Wednesday. “Facebook must stop the foot-dragging and immediately alert everyone whose personal data was compromised by Cambridge Analytica or other third parties.”

Next week, Zuckerberg is slated to testify before the U.S. House Energy and Commerce Committee, as well as a joint hearing of the U.S. Senate’s Judiciary Committee, and Commerce, Science, and Transportation Committee to discuss protection of users’ personal data.