Erica Consterdine, University of Sussex for The Conversation

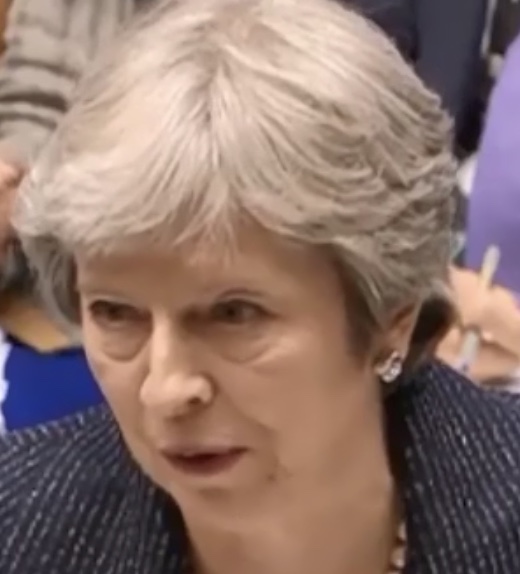

Immigration policy under Theresa May’s tenure might be the most draconian in Britain’s history. Never has an administration focused so much time and effort on an anti-migration policy – and one that is failing by all counts at that.

Countless restrictive measures have been placed on almost every migration stream since 2010, when the coalition government set itself a flawed net migration target. This was driven by a Conservative manifesto pledge to reduce annual immigration from hundreds of thousands of people to tens of thousands. Behind the changes to the immigration rules has been an overarching policy to create a “hostile environment”. The public is now seeing the harsh and inhumane implications of this policy, with the Windrush generation, who helped to rebuild post-war Britain, being denied their rights. But what is this hostile environment and where did this policy come from?

The story starts back in 2004, when the Labour government allowed unfettered access to the UK labour market to citizens of the countries in Eastern Europe that had just joined the EU. As the implications of this were borne out over the 2000s, a political opportunity arose to fuse the once separate issues of EU membership and immigration. That opportunity was grasped by the UK Independence Party (UKIP), which positioned itself as the party to end immigration. With UKIP gaining ground, and an anti-immigration stance looking like the winning ticket, the once socially liberal David Cameron became increasingly authoritarian in immigration policy and discourse. That is what led to the infamously flawed net migration target.

Under then home secretary Teresa May’s leadership, every migration stream was restricted in some way. High skilled routes were closed and a cap was placed on the number of Tier 2 visas issued annually. Eligibility criteria were harshly increased. The remaining seasonal schemes were terminated and family reunification was made harder. A swathe of other stringent measures on language requirements, income thresholds, economic resources, working rights and increasing settlement requirements came in across all migration streams.

But it turned out that reducing immigration was not quite as simple as shutting the doors. This is partly because the UK couldn’t restrict the movement of EU citizens (cue Cameron’s referendum and the road to Brexit). But it was also due in large part to the fact that the UK labour market is structurally dependent on migrants. So to dovetail the restrictive policies, May institutionalised the notion of a hostile environment.

Hostile environment: outsourcing controls

May first spoke about creating a hostile environment in 2012 when challenged on why annual net immigration, then running at about 250,000, was not reaching the promised tens of thousands. Her response: “The aim is to create, here in Britain, a really hostile environment for illegal immigrants”. The broad objective is and was to make life as difficult as possible for any irregular migrant – or any migrant the Home Office judged as potentially illegal in lieu of the correct documentation. They would be “encouraged” to leave voluntarily.

The basic idea behind the hostile environment has two components. First, the burden of proof shifted. Any non-British passport holder was assumed to have violated immigration rules until proven otherwise. Deport first, appeal later. Second, knowing that border controls are only one element of immigration control, the policy shifted to internal controls. This meant that migrants must prove their right to reside at every turn. When they sought medical treatment, rented a home, applied for a driving licence or got a job, they faced immigration checks. Immigration control now extends far beyond the border.

This has entailed outsourcing immigration controls to private actors, and dispersing the immigration control remit away from the silo of the Home Office across Whitehall. Both processes mean the Home Office can pursue its draconian policy while placing the onus and liability on others.

While outsourcing controls is not new, the 2014 Act pushed the practice to the limits. It meant that public sector and private workers – from the NHS, to landlords – with little training or knowledge of the immigration system are now enforcers of immigration control.

Immigration Acts

The hostile environment policy was translated in the Immigration Acts of 2014 and 2016 which included myriad measures to prevent people from accessing employment, healthcare, housing, education, banking and other basic services.

The 2014 Act requires private landlords to check the immigration status of tenants and temporary migrants to make contribution to the NHS. Banks must check against a database of known immigration offenders before opening a bank account. The Act created new powers to check the immigration status of driving licence applicants and revoke those of overstayers, and made it easier and quicker to remove those with no rights to reside.

Extending the hostile environment, the government sought to refocus efforts on illegal working and give more power to enforce immigration laws in the 2016 Immigration Act. This introduced new sanctions on illegal workers, prevents irregular migrants from accessing housing, driving licenses and bank accounts, and included new measures to make it easier to remove illegal migrants.

Concerns were raised at the time about the potential for such document checks to lead to discriminatory behaviour from landlords and others. Such concerns have come to bear with the Residential Landlords Association finding that as a result of the “right to rent” checks on tenants, 42% of landlords are now less likely to let to anyone without a British passport.

![]() Immigration policies so often have unintended consequences which are not anticipated; New Labour’s managed migration and the political ramifications of that policy for the country is a case in point. When the unintended consequences are British residents harassed daily by the state to prove their belonging, obstructing peoples’ lives to work and have a home, policy has not become hostile but downright authoritarian.

Immigration policies so often have unintended consequences which are not anticipated; New Labour’s managed migration and the political ramifications of that policy for the country is a case in point. When the unintended consequences are British residents harassed daily by the state to prove their belonging, obstructing peoples’ lives to work and have a home, policy has not become hostile but downright authoritarian.

Erica Consterdine, Postdoctoral Research Fellow in Immigration Politics & Policy, University of Sussex

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.