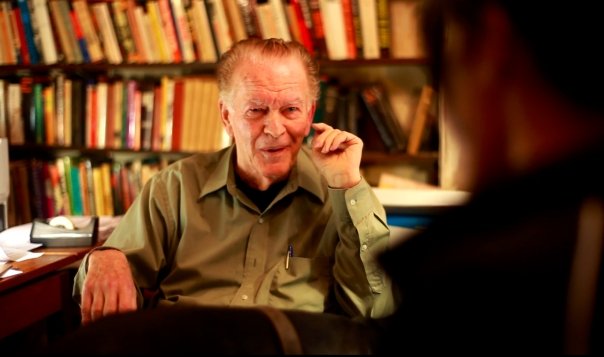

Gene Sharp, who passed away at the age of 90 on Sunday, was not only a key figure in the development of a whole new field of study devoted to helping people realize their own power, he was a key figure in the lives of so many who found inspiration in his work and took it in new directions. It is no exaggeration to say that Waging Nonviolence would not exist were it not for his pioneering research demonstrating the undeniable power and effectiveness of nonviolent struggle. It is also true that his early encouragement — and desire to publish an original piece with WNV, just two years into its existence — gave us a much needed boost of confidence.

Nearly everyone who has taught, researched, written about or engaged in nonviolent struggle owes some debt to Gene Sharp. And since the obituaries don’t have room to share their remembrances and tributes, we have collected some of them here. While the following stories come from only a small sampling of the activists, organizers, scholars and writers whose lives he touched, they give a glimpse of the profound impact that he had on the world.

—

It’s been a profound privilege of my life to learn from you. The world is a better place because of your path-blazing audacity. Thank you for sharing your genius with the world. Rest in peace, my friend.

– Jamila Raqib is the executive director of Gene Sharp’s Albert Einstein Institution and a Director’s Fellow at MIT Media Lab

—

I can never forget the day I first met Gene Sharp. I was an Army Senior Fellow at the Center for International Affairs at Harvard University. I saw a notice taped to a window stating there would be a meeting of the Program For Nonviolent Sanctions at 2 p.m. that day. As an Infantry officer with almost 25 years learning the skills of combat and executing those skills with two combat Infantry units, I decided I would drop in just to see what peaceniks and draft dodgers looked like and talked about. Soon, a small man walked to the front of the room and introduced himself. “I am Gene Sharp,” he said. “Strategic nonviolence is about seizing political power or denying it to others.”

After the meeting, I introduced myself to Gene and asked if I could meet with him, since my career was doing what he had talked about — except my career was about waging violence for the same purposes. After a meeting the next day, which lasted three hours, my life was changed regarding those who advocated nonviolent actions, if they knew and followed Gene’s concepts. To be more effective, in my view, Gene Sharp’s approach could be expanded to include strategic and tactical operational planning, propaganda development and distribution and understanding the meaning of Sun Tzu’s “Knowing your enemy and you will know the outcome of a thousand battles.” Gene became my mentor for almost two decades.

I know Gene enjoyed introducing me to his friends and colleagues as “Colonel” Bob Helvey. He showed me a viable alternative to war in pursuing security and other national interests. A society can no longer defend itself against a wannabe tyrant using violence against the modern state. Just maintaining our second amendment rights will not deter an oppressor. Nonviolent struggle is a force more powerful. We traveled together in many countries. The peacenik and the warrior worked well together!

– Robert Helvey is a retired U.S. Army Colonel and the author of “On Strategic Nonviolent Conflict: Thinking About the Fundamentals”

—

All of those in the peace movement, whether they have been imprisoned on charges of civil disobedience or have taken to the peace studies classrooms, owe a large debt to Gene Sharp. Through his many books on nonviolence written over the decades, he has consistently been the idea man that kept us grounded. In the 35 years of my classroom toil, not a semester has passed without reading one or more of Gene Sharp’s essays.

I had a long conversation with Gene Sharp in 2011 when he came to Washington, D.C. to receive the El-Hibri Peace Education Prize. Gene, self-effacing and gracious, was characteristically modest about his long record to champion alternatives to violence.

– Colman McCarthy directs the Center For Teaching Peace in Washington, D.C., and is a columnist with the National Catholic Reporter

—

Although I wasn’t even introduced to Gene Sharp’s work until 2005, I can say without a doubt that he has fundamentally shaped both my professional and personal outlook more than almost any other single person. I find that my own life has been enriched by the way in which I now understand power, and I have been able to pay this forward to thousands of students over the years. It is impossible to imagine that the study of civil resistance and nonviolent strategy would be anywhere near as evolved as it is today without the contributions of Gene Sharp. His work very likely has contributed to the liberation of countless people over the years, and will probably do so into perpetuity. That is quite the gift to humanity.

– Cynthia Boaz is an associate professor in the department of political science at Sonoma State University

—

I got to interview Gene Sharp when I was at the New Yorker, and his books were hugely useful to me when I was trying to figure out ways to escalate the Keystone pipeline campaign. But my favorite memory of him is from a meeting in an upstairs office in Central Square Cambridge some winter evening in the late 1970s. The Clamshell Alliance was planning for an attempt to take over the Seabrook nuclear power station, and I was a journalist covering the scene. Some of the more zealous activists were worried that the police would spy on them from helicopters so they were planning to use weather balloons to stretch steel cables so the choppers would be afraid to fly nearby. Gene had come by to consult, and I remember him listening to this, and then simply saying: “How is that different from telling them you have an anti-aircraft gun and you’ll shoot them down?” No one had a good answer, and the Seabrook occupation remained steadfastly nonviolent.

– Bill McKibben is an author, educator, environmentalist and founder of 350.org

—

It took a Hindu by the name of Mohandas Gandhi to grasp the power of Thoreau’s Christian-based civil disobedience. And similarly it took a (at the time) young academic by the name of Gene Sharp to unlock the strategic power of nonviolence from India’s most well known activist. Gene was bold enough to run against the prevailing winds. He was detailed enough to back it up. And he was insistent in his revolutionary argument that it is not might — but people’s tacit or explicit agreement with the powers-that-be — that keeps those powers in place. His lessons will echo long beyond his name. And we thank him for it.

– Daniel Hunter is a trainer and organizer at Training for Change

—

It took a little time to convince Gene that doing a documentary was a good idea, but eventually I received an email from him where he said he understood the power of film to convey his message long after he was gone. That became my mission — his work was always going to live on in his books in every corner of the world, but I wanted to create a film where the viewer would feel like Gene was talking directly to them. Shortly afterwards he phoned me up and said, “Honestly, how much have you read!?” I was bit stumped by this question because I’d only completed “From Dictatorship to Democracy” at that point and dipped into the case studies in “The Politics of Nonviolent Action.” I fudged the question and thought I’d gotten away with it, but a week later an enormous box of books arrived at my flat in London with almost everything he’d written in it. He sent a note which read, “I like a well-informed interviewer!” Later I saw that was typical of Gene — he was quite capable of gently upbraiding any potential upstart who didn’t think they needed to study his material in depth. He’d say, “If you want to remove a dictatorship, you can read 900 pages. If you can’t even read 900 pages then you’re not serious!”

I was really privileged to go touring the film around Europe with him. I think we all understood that it would probably be his last foreign trip, and he enjoyed it enormously. He was treated like a rock star wherever we went — huge cinemas full of sometimes 700 people gave him emotional standing ovations. I remember looking out from the stage on one occasion to see the official photographer at the event had to stop taking photos to wipe tears out of her eyes. He was kind to everyone who wanted to meet him, caring and generous with his time, but there was an obvious steely and dogmatic core of his personality which kept him going through his toughest moments. His story of dogged determination to improve the world despite operating against incredible odds inspired so many people, but he was relentlessly modest about his contribution. Had it not been for the dictators who denounced him, I would never have known his name.

– Ruaridh Arrow is the director of the documentary “How to Start a Revolution” and the author of a forthcoming biography of Gene Sharp

—

Gene and I were in Moscow at the invitation of the Living Ring after the August attempted coup d’etat against Gorbachev in 1991. Boris Yeltsin and the others opposing the coup were hiding out in the parliament building, while 10,000 people (the Living Ring) surrounded it for three days and nights, nonviolently facing the tanks and soldiers who had order to attack. The Living Ring wanted training in how to nonviolently defeat future attempted coups against the government. Gene gave talks and we led workshops on nonviolent means to defeat further coup d’etats. It was a real privilege to work with Gene who selflessly shared the power of nonviolent struggle with people, groups and movements who wanted to use peaceful methods to challenge oppression and injustice.

– David Hartsough is the author of “Waging Peace: Global Adventures of a Lifelong Activist” and the director of Peaceworkers

—

Gene Sharp made fundamental and original contributions to the theory and practice of nonviolence, a contribution of immense significance in an age of brutal violence under the spreading shadow of virtual extermination.

– Noam Chomsky

—

I first met Gene 18 years ago while a graduate student at the Fletcher School. The simple but revolutionary concept that Gene described so clearly, that power is ultimately grounded in the consent and cooperation of ordinary people, was exciting for someone like myself studying internal wars and violent conflict. It didn’t take long before I had an appointment with Gene at the Albert Einstein Institution.

What struck me most in meeting Gene was the absolute seriousness with which he undertook his research and writing. Documenting the strategies and tactics of nonviolent struggle was not a theoretical exercise for Gene. He knew it had profound, real-life implications for those living under the boot of repression around the world. His interactions with activists from Burma, Palestine, Serbia and beyond demonstrably grounded his work.

The impact of Gene’s work on those on the front lines is most impressive. I’ve met many activists over the years, from Ukraine to Egypt to Zimbabwe, who’ve told me how Gene’s works, which have been translated into dozens of languages, have guided their freedom struggles. While working at ICNC and later in the U.S. State Department, I’d regularly send activists, civic leaders, and policymakers Gene’s writings, including those famous 198 Methods of Nonviolent Action. His From Dictatorship to Democracy is, for activists, a tool of liberation.

I am grateful to Gene for his groundbreaking and meticulous research, for laying the intellectual foundation for the field, and for providing peoples around world with effective tools to challenge injustices and build more inclusive, just, and peaceful societies. Rest in peace and power, Gene.

– Maria J. Stephan directs the Program on Nonviolent Action at the U.S. Institute of Peace and is the co-author of “Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict.”

—

Gene Sharp was a pioneer. He was our pioneer, who courageously put nonviolence on the map of a violent world, making possible the work that we do. His groundbreaking book, “Making Europe Unconquerable,” and his many writings on nonviolent tactics have been widely translated and widely read. It’s impossible to estimate how many people in our world today live in political freedom because of what Gene Sharp thought and did. How fitting that he passed on almost to the day that his great mentor, Mahatma Gandhi, fell to an assassin’s bullet.

– Michael Nagler is the founder and president of The Metta Center for Nonviolence, as well as the author of “The Search for a Nonviolent Future”

—

I first met Gene in 1955 when he moved to London to work for the pacifist weekly paper Peace News. I remember him coming to a party at the headquarters of the Peace Pledge Union organized by a group I belonged to, the Pacifist Youth Action Group, or PYAG. Amongst other things, PYAG organized pickets outside prisons where conscientious objectors were being held, helped pack copies of Peace News for dispatch every evening, and had a platform at Speakers Corner in Hyde Park afternoons. Gene on the occasion of the party was dressed informally in casual shirt and jeans, spoke about the radical tradition of the early trade union movement in the United States and got us singing songs from that period and African-American spirituals.

He was a few years older than the majority in PYAG, had spent time in a U.S. penitentiary for draft refusal during the Korean War and had a deeper knowledge than most of us of the Gandhian tradition of nonviolent action. While he is chiefly known for his scholarly work on Gandhi’s ideas and campaigns, and more generally on civil resistance and civilian-based defense, he should be remembered also for his early commitment to fostering grassroots campaigns against war.

In the late 1950s Gene worked closely with the Committee for Direct Action against Nuclear War — the radical anti-nuclear campaign body that was subsequently renamed the Direct Action Committee against Nuclear War — which organized the first 50 mile walk from London to the Atomic Weapons Research Establishment at Aldermaston in 1958. It also adopted the now universally recognized “Peace Symbol,” designed by artist Gerald Holtom, which was featured on the leaflets for the march and on a briefing document written by Gene on maintaining nonviolent discipline. Later that year when the committee organized an illegal occupation and sit-down at a U.S. rocket base in Norfolk, Gene vigorously defended its decision against critics, who argued that the action was undemocratic.

Over time the emphasis of his work shifted more to analyzing and promoting nonviolence as a strategic option rather than a moral imperative, and he somewhat distanced himself from the peace movement as such. He will be remembered not only as someone who advanced the understanding of a crucial instrument of social change, but took practical and effective action to promote it.

Michael Randle is the former chair of War Resisters International and has been involved in the peace movement as an activist and researcher since the 1950s.

—

Gene Sharp was vital, all these 90 years, in part because he was a true internationalist — one who never stopped exploring even when his body would not allow it. Decades ago, when we first met, discussing in part my work with his old friend, Pan African pacifist Bill Sutherland, his distinct erudite demeanor gave way to an almost boyish enthusiasm about the possibilities before us. Just a few years ago, meeting in his tiny East Boston study, I introduced him to Burundian student activist Sixte Vigny Nimuraba — with that same passion as present as ever. All around the world, for many years to come, Gene will not be missed: because his ideas will live on.

– Matt Meyer is national co-chair of the Fellowship of Reconciliation

—

My personal encounters with Gene were phone calls or drop in visits over the the years, during which he would always stop what he was doing to say hello, share his latest work, and answer my questions on the topic of the day. After the Arab Spring, I asked him why he thought Libya would choose civil war to overthrow their dictator, when Tunisia and Egypt had just demonstrated a less painful alternative. He explained how defecting military factions with lots of weapons at their disposal and support from NATO quickly rushed in to do the job.

What Gene gave us was a realistic way out of our insane belief that we must kill people to create a safe world. For me he created a bridge between the Sermon on the Mount and realpolitik. What a thrill it is now to see so many scholars and activists making that bridge wide and welcoming.

– John Reuwer is adjunct professor of conflict resolution at Saint Michaels College, Vermont

—

Gene Sharp was such an unique person, and I feel so privileged I got to know him personally and can call him my friend. His work was certainly academically and scientifically very significant, but more importantly — for me and activists worldwide — it inspired thousands of people around the globe to better learn how to fight for freedom, human rights and democracy. I learned about his work in 2000, while leading the Serbian nonviolent movement OTPOR! (resistance). Since then, I have never stopped studying and applying his great work, which has left a significant stamp on people-power-driven movements worldwide. I am sure that his legacy will be even more important in the age that we are living in, the age when human rights and democracy seem to be under permanent threat. I feel that this great loss will serve as a boost and inspiration to carry on the torch of nonviolent activism with even stronger commitment.

A last salute to Gene, my friend and inspiration. Let’s make sure his legacy, ideas and marvelous insights into how people can empower themselves shines for generations to come. Great ideas, unlike great people never die!

– Srdja Popovic is the founder of CANVAS and author of “Blueprint for Revolution”

—

I was first introduced to Gene Sharp’s writings as a left-wing student activist in the 1970s. Though I shared with my leftist comrades their strident opposition to U.S. imperialism and the importance of what was then called Third World solidarity, I was uncomfortable with their romanticization of armed revolution. These largely white middle-class college students would never know the horrors of counter-insurgency warfare inflicted against populations who resisted their oppression through armed struggle.

Their response was that, given how structural violence (deaths from malnutrition, preventable diseases, etc.) was responsible for ten times the deaths of behavioral violence, supporting an armed revolution that would end the structural violence was actually was thereby morally defensible. Even putting aside the propensity for successful armed revolutions to turn into autocratic governments that also fail to successfully address structural violence, I was not convinced that it was an either/or situation. There had to other ways than armed revolution to topple autocracies. Through his study of centuries of nonviolent struggle, Gene made a convincing case on utilitarian grounds that nonviolent struggle was a better means of resistance.

Most of my fellow student radicals remained unconvinced, in large part because there were few concrete examples at that time of largely nonviolent movements bringing down authoritarian regimes. In the 40 years since, however, over 50 autocratic governments have been toppled through unarmed civil resistance movements, many of which were influenced by Sharp’s writings.

– Stephen Zunes is a Professor of Politics and International Studies at the University of San Francisco