Published in July 2013 by Democracy Now!

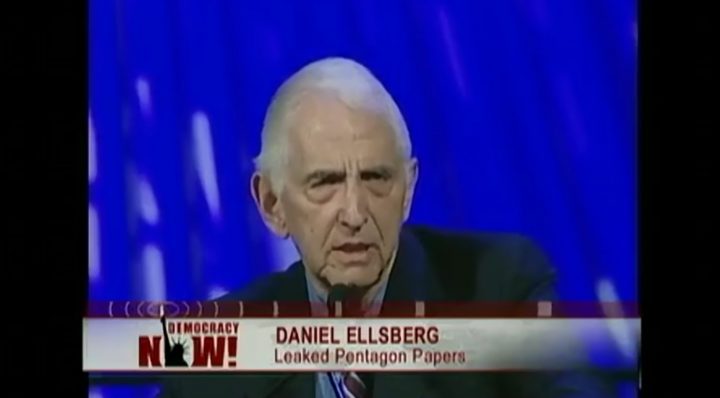

Forty-one years ago, Beacon Press lost a Supreme Court case brought against it by the U.S. government for publishing the first full edition of the Pentagon Papers. It is now well known how The New York Times first published excerpts of the top-secret documents in June 1971, but less well known is how the Beacon Press, a small nonprofit publisher affiliated with the Unitarian Universalist Association, came to publish the complete 7,000 pages that exposed the true history of U.S. involvement in Vietnam. Their publication led the Beacon press into a spiral of two-and-a-half years of harassment, intimidation, near bankruptcy and the possibility of criminal prosecution. This is a story that has rarely been told in its entirety. In 2007, Amy Goodman moderated an event at the Unitarian Universalist conference in Portland, Oregon, commemorating the publication of the Pentagon Papers and its relevance today. Today, we hear the story from three men at the center of the storm: former Pentagon and RAND Corporation analyst, famed whistleblower, Daniel Ellsberg, who leaked the Pentagon Papers to The New York Times; former Alaskan senator and presidential candidate Mike Gravel, who tells the dramatic story of how he entered the Pentagon Papers into the congressional record and got them to the Beacon Press; finally, Robert West, the former president of the Unitarian Universalist Association. We begin with Ellsberg, who Henry Kissinger once described as “the world’s most dangerous man.”

Transcript

This is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form.

AMY GOODMAN: We turn now from Snowden to Daniel Ellsberg. Forty-one years ago, a small, independent press, the Beacon Press, lost a Supreme Court case brought against it by the U.S. government for publishing the first full edition of the Pentagon Papers. It’s now well known how The New York Times first published excerpts of the top-secret documents in June of 1971, but less well known is how the Beacon Press, a small nonprofit publisher affiliated with the Unitarian Universalist Association, came to publish the complete 7,000 pages that exposed the true history of U.S. involvement in Vietnam. Their publication led the Beacon Press into a spiral of two-and-a-half years of harassment, intimidation, near bankruptcy and the possibility of criminal prosecution. This is a story that’s rarely been told in its entirety.

In 2007, I moderated an event at the Unitarian Universalist conference in Portland, Oregon, commemorating the publication of the Pentagon Papers and its relevance today. Thousands of people were in the audience. Today, we hear the story from the three men on the stage at the center of the storm: former Pentagon and RAND Corporation analyst, famed whistleblower, Daniel Ellsberg, who leaked the Pentagon Papers to The New York Times; we also hear from former Alaskan senator and former presidential candidate Mike Gravel—he’ll tell the dramatic story of how he entered the Pentagon Papers into the congressional record and got them to the Beacon Press; finally, Robert West, the former president of the Unitarian Universalist Association.

We begin with famed whistleblower Daniel Ellsberg, who Henry Kissinger once called “the world’s most dangerous man.”

DANIEL ELLSBERG: There were 7,000 pages of top-secret documents that demonstrated unconstitutional behavior by a succession of presidents, the violation of their oath and the violation of the oath of every one of their subordinates—I, for one—who had participated in that terrible, indecent fraud over the years in Vietnam, lying us into a hopeless war, which has, of course—and a wrongful war—which has, of course, been reproduced and is being reproduced right now and may occur again in Iran. So the history of that, I thought, might help us get out of that particular war.

Let me skip over the intervening 22 months then, really, which passed after I first copied the Pentagon Papers, when I was trying to get them out, and the senators and others who were not up to the task of putting them out, people who were otherwise very admirable and very credible in their antiwar activities: Senator Fulbright, Senator McGovern, Gaylord Nelson, Senator Gaylord Nelson, various others. Except for Nelson, Fulbright, McGovern and Senator Mathias, some of the best people in the Senate, had, in fact, contrary to the way it’s often reported, not refused to bring out these papers when I discussed them with them. Each one agreed to bring them out and then thought better of it over a period of time, said they just couldn’t do it, take the risk—in effect, in other words, “You take the risk, but I’ve got an important position here, and I can’t ruffle the waters here.”

I read in—I did give them to The New York Times — sorry, to Neil Sheehan, but with no assurance that they would come out in the Times, and for reasons not clear to me still, Neil, who, again, acted very admirably and credibly, as did the Times, which took a great risk in deciding to publish the papers, did not tell me they were bringing them out. I’m not clear to this day quite why that was. But so I continued up—while they were working to get the papers ready for publication in the spring of 1971, I was still worrying and trying to see where I could get them out. I approached Pete McCloskey, who, again, agreed to do it, but took efforts to get them officially from the Defense Department before he did that. He was very supportive of me during my trial later.

And I also thought then—I read in the paper about a Senator Gravel, whom I really didn’t know much about, from Alaska, who was conducting a filibuster against the draft, which was exactly what should have been done. By the way, I had raised as a litmus test—I probably never told Mike this—I had raised the idea of a filibuster with a number of senators as a litmus test to see whether they were the kind of person who might go one step beyond that and maybe put out these papers. And in every case I got serious answers—they weren’t frivolous—but the point was, as Senator Goodell put it to me, “Dan, in my business, you can’t afford to look ridiculous. You cannot afford to be laughed at.” And he said, “If I could find other people who would join me, I would do it.” I heard that, by the way—I’ll mention—each name I’m mentioning here is very—the top people in the Senate. Senator—oh, darn, at my age I forget some of these names—but anyway, other senators said much the same: “If I could find somebody else to go with me, I would do it, but I can’t do it by myself. I would look foolish. I can’t afford that.”

So here was a senator who was not afraid to look foolish, basically, and that’s the fear that keeps people in line all there lives. Don’t get out of line. It’s the kind of thing you learn at your mother’s knee to get along, go along—your father’s knee. And don’t stick out, don’t make yourself look, you know—don’t raise your head, sort of this thing, and look ridiculous. But he wasn’t afraid to do that on a transcendent issue like the draft in the middle of this war. So I thought, “OK, maybe this is the guy.” I hadn’t met—I had met the other ones before, I knew them. So I didn’t know him. I said, “OK, he’s doing a filibuster.”

So I was quite shocked to learn from a friend in the Times that the building was locked down. They were worried about an FBI raid and an injunction, because they were copying this seven—they were putting out this big study, which I hadn’t been told. So I go, “Well, that’s very interesting.” And meanwhile, I had these papers in my apartment. The FBI might come any minute, and I had already had a scheduled meeting with Howard Zinn that night, with our families—his wife and my wife—to go to see Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. And so, I called Howard, didn’t say it over the phone, but I said, “I’ll come to your apartment. We’ll go from your place,” and I went there with the papers, and asked him if I could dump them in his apartment for that night, which he said, you know, “Fine.” I had already shown him. He was one of two people I’d shown—Noam Chomsky and Howard Zinn, both—some of these papers earlier.

So, the papers came out that night, and we got them at midnight in Harvard Square. There wasn’t a lot of attention on Sunday to them, which everybody was surprised at in The New York Times. The TV didn’t pick it up, and so forth. But on Monday they had got attention, and the key thing was that John Mitchell, the Attorney General, then asked a request of The New York Times that they cease publication of this criminal act, stop this. Remember, they had lost their law firm already, Lord & Day, on the grounds that their lawyers had told them this was treason and a criminal act, and they wouldn’t represent them. And Mitchell was confirming that and telling them that they must stop.

Well, they went ahead; they did not obey the request. So the next day, Tuesday, they enjoined The New York Times for the first time in our history. We know from the tapes now that Nixon had asked Mitchell on the tape—I’ve heard this—the day before, on Monday, Mitchell wanted to put the Times on notice. And, of course, Nixon says, “Have we ever done this before?” And Mitchell says, “Oh, yes, many times.” Terrific legal advice from the bond lawyer. It had never been done in our history and, of course, led to a constitutional battle, which Nixon lost and the attorney general lost. But they did enjoin it, and so the question was what to do next.

I hadn’t been identified yet, but I decided, on the base of one other person who suggested it to me, that I give it to The Washington Post. And meanwhile, I had called up Gravel’s office—I was still able to use a phone, not my home phone, but I went out to a pay phone—and said to the person there, “Is your boss interested in putting out the Pentagon”—I didn’t say the “Pentagon Papers”—”Is your boss intending to keep up this filibuster? Is he going to stay there?” They said, “Oh, absolutely.” I said, “Well, I’ve got some material that could keep him reading till the end of the year, if he’s interested in it, you know.” And that being the number one story at the moment, he sort of guessed what it was. And I think Mike will go on from there. He went on and informed Mike of this possibility. But the question then was how to get them to him. I could no longer travel, as I’d planned to do.

So I’ll end with this story, which will tie in with—Mike can take up the story from there. The question was how to get it to him. I was not in a position to travel at this point. So I did arrange with a former colleague from RAND, Ben Bagdikian, an editor of The Washington Post who had spent a year or two at RAND as a consultant—mic’s down? Can you hear me? OK—Ben Bagdikian, I said, I knew. So I called him up and arranged to have him come to Boston—yeah, it was a colorful story, which I think is told in the thing you have there. He came to Boston, Cambridge. We took a room at the Treadway Inn near Harvard Square, and my wife and I brought these boxes of ill-assorted papers, tremendous stuff we hadn’t collated ideally, to him, and we spent the night with him collating and putting them in an order that he could take back with him. And in the morning he had this big box. He didn’t have—he needed a cord for the box and asked the Treadway, and the motel owner said, “Well, somebody’s been tethering a dog outside. I can give you the dog cord.” So we tied up the box, and he went off and put it on.

My wife and I looked at the television before we went home. We had been all night on this now. This was about 7:00, 8:00, 7:30 in the morning, and there was our home being—with some FBI agents knocking on the door on live television. And they were knocking on the door, so we thought, “Hmm, maybe this isn’t the best time, you know, to go back home, actually.” And what had happened was that Sid Zion, who was mad at the Times for having fired him, had rather quickly found out who their source was, and to get back at them, he had revealed it on a radio show, the Barry Graves show, the night before. So the FBI was at my door, and having seen it on television, I was now in a position to not be caught and to put out the other copies.

Well, the reason—so we didn’t go home. We went underground in Cambridge. For the next 13 days, the FBI conducted what the papers said was the biggest manhunt since the Lindbergh kidnapping, and they were—we were in Cambridge—they were all over the world, in the south of France, in [inaudible] in California. I had a feeling there was a good deal of junketing going on, actually, by the FBI looking for us, but meanwhile we were putting it out to these other newspapers.

And I will mention, as one last point here, it’s always the Times and the Post who are mentioned, of course, as having had the courage to go along with this, as we spent the 13 days putting it out. That’s why I was evading the FBI. I had other copies, and I was putting them out. Actually, there were four injunctions, also The Boston Globe and the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, before they gave up on injunctions, or there would have been more. Altogether 17 other newspapers published those papers. And oddly, they don’t seem to mention it much in their own histories. They don’t commemorate this, as we’re commemorating the Beacon Press right now, but they should. That was a wave of civil disobedience across the country by publishers who were being told that they were violating the Espionage Act, they were committing treason, they were hurting national security. They read the documents we gave them and decided they didn’t agree with that as Americans and patriots, and they published them. So it was institutional civil disobedience of a type—I don’t really know of any country or any other journalists, and that’s a kind of freedom and courage we need to celebrate and we need to continue. So, thank you very much.

Read the full article here