By PETER COVILLE 22 January 2018 for openDemocracy

Is loneliness the price we pay for an ideology that privileges individual freedom and ‘choice’ above the collective and communal; that sees attachment to others as an obstacle to the pursuit of profit?

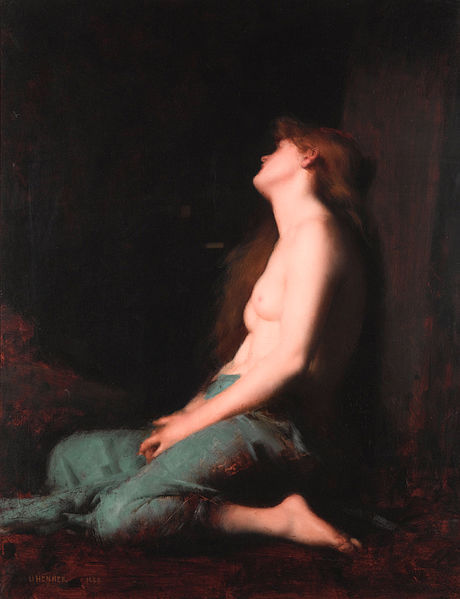

Anyone who really knows what loneliness is knows it well: that permanent vague aching sensation in your chest when you haven’t meaningfully engaged with another human being for days or weeks or even months, and yet here you are, alone once again. When it finally comes, that moment when someone says something to you that goes beyond work orders or neighbourly pleasantries, or touches your hand, or hugs you, can be so powerful that you fear your legs will give way under you, or that you will start sobbing uncontrollably. But you manage – more or less – to maintain appearances.

Anyone who really knows loneliness, of this deep kind which lasts for weeks and months rather than a few lonely hours, is not in the least surprised to hear the research findings which tell us that being lonely is the health equivalent of smoking fifteen cigarettes a day, or that loneliness significantly increases the risk of premature death.

According to research by the Coop and the Red Cross, loneliness affects at least nine million people in Britain. The Campaign to End Loneliness reports that over three-quarters of GPs say they are seeing between one and five patients a day who have come in mainly because they are lonely. Reflecting no doubt this growing social reality, there has been a lot of talk in the media about the problem of loneliness over recent years, and charitable and campaigning organizations dedicated to addressing the problem have mushroomed. Most recently, following the death of MP Jo Cox, who campaigned energetically on loneliness, the Jo Cox Commission on loneliness was set up by the Government last year, and has recently published its recommendations. The Government has acted rapidly, giving responsibility for loneliness to the Minister for Sport and Civil Society, Tracey Crouch, and promising to publish a cross-governmental strategy on the issue later in the year to implement the other recommendations of the Cox Report. So that’s it then: due to the efforts of many determined campaigners, loneliness has finally come to the attention of our leaders, and they have a plan! We can move on to other matters.

But if we are to really address the problem we should ask where this epidemic of loneliness comes from. It would be instructive to consider the deep historical roots, as well as the more recent ideological underpinnings of loneliness.

Starting with the historical roots, which go back to the Enlightenment thinkers, loneliness is to some extent the negative corollary of the modern desire for individual freedom from the restrictions and constraints of traditional institutions and forms of life: religion, family, village, tyrannical bosses and so on. Individuals want to exercise greater choice over their work, the place they live, their moral and political beliefs, their sexual orientation and so on.

But the downside of this desire is the creation of the more mobile and restless individuals that we are today, who choose to opt out of traditional communities like extended family, neighbourhood, church, or union. The difficulty is that we cannot always find substitutes for the fellowship and feeling of community these institutions provided and which they need. Increased demand for individual liberty tends to produce more lonely individuals. This is why it is so important for modern societies to create institutions and places which foster community and togetherness, places that people know they can find company and fellowship whilst not sacrificing their individual freedom.

But instead of countering this historical trend with new ways of creating connections between individuals whilst respecting this legitimate desire for freedom, the neoliberal ideology which has dominated in recent decades has reinforced the causes of loneliness in two ways.

Firstly it has reinforced our image of ourselves as absolutely free beings. Neoliberal economics portrays us as rational autonomous choosers of lifestyles, consumer goods – and self-creators for whom any medium or long-term projects, or any attachments to others, are obstacles to our freedom at the moment of choice. Wealthy, “successful” individuals present themselves to us as “self-made men” who owe everything to their hard work, and who we should admire and emulate, whilst omitting to mention the many people who helped them on the way up – and the many ways they benefitted from state provision of health, education and other public services.

Frederic Lordon, Colin Cremin, and others have described the way in which neoliberal capitalism is not content with simply dominating its workforce, but makes us the willing agents of our own enslavement. Many of us have become joyful team-players and competitive careerists who are happy to sacrifice family and personal life to increase the bonuses of the members of the board, or shareholders’ dividends, whilst our rewards remain largely symbolic (pats on the back from the boss, “best employee” awards, promotions etc).

Along with economic globalization and the financialization of capital, this colonisation of the “soul” – of the previously largely private domain of desires and our emotions – is probably one of the characterizing features of neoliberalism. One result is to see ourselves as masters of our own fate, independent of and separate from others in both our professional and our private lives.

The second way that neoliberalism fosters loneliness is by eliminating anything which is not “productive” in a narrow economic understanding of this term – anything which does not produce a return-on-investment for shareholders. Governments of all colours have in recent years implemented policies which dissolve or undermine youth clubs, sports clubs, libraries, and charities supporting disabled or older people, or other vulnerable groups – exactly the kind of collective projects which protect people from loneliness in modern freedom-loving societies. At the same time, the army of volunteers who once ran such community projects is drying up, exhausted from having had every last drop of their productivity – that is, their energy – squeezed from them in their day job. These are some of the real causes of contemporary loneliness.

I am not saying that we ought to reject the recommendations of the Cox Commission, which have received the backing of Jo Cox’s husband, Brendan. But we should be under no illusion about how much they can achieve in a socio-economic system which generates loneliness – not to mention an epidemic of mental health problems – on a massive scale.

An analogy can be drawn here with foreign aid: wealthy countries colonize majority world countries for decades or centuries, plunder their natural and human resources, and then, after granting national independence, establish a system of trade rules and bank loans which entrench dependence and poverty, and make it impossible for poor countries to develop. We are then told that we can solve the problem of global poverty by offering a little bit of aid. It is the same with loneliness: we can only address the root causes of loneliness by first understanding them, and then by changing the nature of our society so that it no longer generates loneliness. A “Minister for Loneliness” is not going to do it.