By Jhon Sánchez

As a Colombian writer living in New York, I owe part of my literary influence to Puerto Rico. Writers like Miguel Piñero, Doña Julia Burgos, Mayra Santos Febres and many others have inspired my career. Every year, I have the fortune of attending El Festival de la Palabra that takes place in New York and San Juan during the month of October. There I’ve met different authors and exchanged ideas over wine. Of course, our dear Puerto Rico is suffering after Hurricane María, and all of that led me to take San Juan Noir from my bookshelf with the idea of talking to the authors about that captivating anthology. Let’s see if we’ll find some hope in the noir.

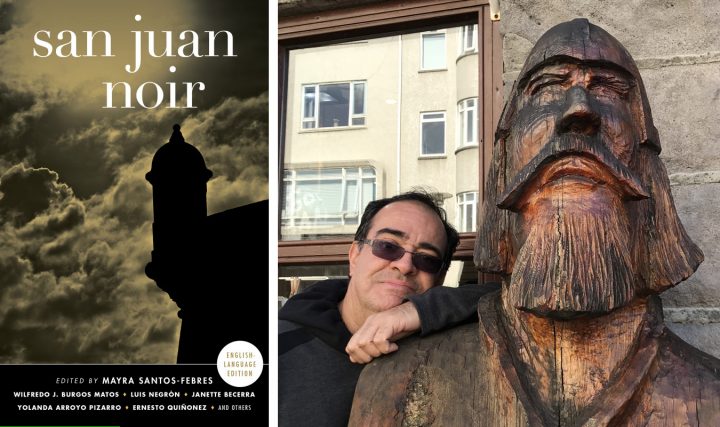

Today, I’m talking to Jose Rabelo:

1) You’re also a physician so to ask how you’re doing acquires a special significance. How are you doing?

I’m doing good; standing again after Hurricane María with my family and the people of Puerto Rico. Also, I’m starting to work with some creative writing projects interrupted by September’s natural event. As a person I’m looking at the world in a different way after these postapocalyptic experiences. I’m hearing the stories of my patients, students and friends. Due to the lack of electricity for 45 days (in my case), these days I’m getting updates of the events watching the news related on how the citizens are emerging from their tragedies. The images are breathtaking but the recovery of my people is more impressive.

2) Why is it important to talk about culture and literature at this time in Puerto Rico?

I would tell you that it is important to talk about this theme as frequently as possible. As a Commonwealth of the USA, many people still think that Puerto Rico is an English speaking country. For many years we have been defending our Spanish, although it has been menaced. Spanish is an essential aspect of our culture, and culture is the heart of our country, the soul that will not perish in our nation. At these times of sorrow and loss, the arts are nurtured with the varied views of our artists. In terms of literature our minds are processing all the dialogues, situations and vital moments to be transformed in words. Some literary groups are asking for texts related to the hurricane events in hopes of developing and publishing anthologies. Although a lot of material things were lost, our energy to create has been enriched. I’m sure that many ideas are boiling around there, a product of the crisis. In Puerto Rico, many of our literary works were inspired by a variety of social problems, from Manuel Zeno Gandía’s La charca to Abelardo Díaz Alfaro’s Terrazo. These books show the reality of our island in periods of social and political turmoil, another kind of what I call “the endless social hurricane”. So the crisis could be the fuel for inspiration and transpiration of our writers in these and many times.

3) Hurricane Maria is a real horror story. How is all this tragedy nurturing your imagination?

This natural event was like the story of “The Wolf is Coming”. Many people didn’t believe the weather experts. During previous hurricane seasons many phenomena were predicted and at the last moment they took another path, far from the island. I think that many people thought that would occur this time. Many things happened, others didn’t occur but the imagination creates its own plot to develop many possible stories. During the days of the tragedy I took seven little diaries to write my impressions. I wrote without much analysis, simply observing the actions of my people and hearing their voices through the radio. Many of these tales could be heard through the only radio station that was in function. Some people from USA were searching for their families, others (the few who had communication) were taking about flooding, landslides and deaths. Many of these testimonies were hyperbolic. I remember one of those. One person told about thousand of dead bodies floating adrift through the river but later it was clarified that there were really a few cadavers after a zone of a cemetery was affected by river flooding. At nights we had plenty of time to watch the stars, to depart with our neighbors and to tell stories to our children. It was like traveling on a time machine where we had the opportunity to speak for long time instead of watching a computer screen. Seeing the children playing on the streets was like watching humanity flourishing again. No mobile communication was available in the surroundings of our homes, so we had to move to highways to catch some signal. Years ago, after similar events, you had the opportunity to see lines of cars looking for water wells in some points of the highway, but this time the line was due to the search of “wells of cell phone signals”.

4) Let’s talk about your story in the anthology San Juan Noir. The story is called ‘Y’. I love the story for its mathematical language that turns out to be very poetic. Can you comment on that?

When I was invited to send a story to San Juan Noir I felt that invitation as a challenge. During many years I had been teaching creative writing. In one of my courses I ask my students to write a noir story. That invitation from Mayra Santos Febres made me feel like a challenged student. Previously, I had written some noir tales, “Lisboa” and “Lo que pudo ser” (Esquelares, Isla Negra Editores, 2012), but I wanted to create a new one for San Juan Noir. I decided to write about a lost adolescent. I saw San Juan as a map with all its poetic coordinates and the best way to present that image was to transform a mathematics teacher into a detective with some obsessive thinking in his search for a talented student. For me the map of the train route was perceived as a murdered victim’s big upper extremity, so part of the thoughts of the character would take place on that train. At that time I took a ride to the places were the plot is set. That contact with my memory and the setting helped me to write the details of the story. For moments I was transformed in a “method writer” and put myself into the body of the teacher and other times inside the flesh of my female character. The mathematical formulas mentioned are the atmosphere or reflection of a mental process that permeates in the search and the poetic thinking on the narrator in second person.

5) What was the source of the inspiration for the story?

Years ago a great friend told me the story about a promising student that was absent to school very frequently. When the social worker started to investigate the cause, she discovered a similar situation as the one presented in ‘Y’. That impressed me and I never forgot it. When the opportunity appeared I was interested in developing that anecdote into a literary world. I think that adolescence is sometimes the dark age of our development, conflicts that seem insignificant could be pivotal during those years. This is not only true with Puerto Ricans, also at the universal level. So I tried to recreate some aspects of the original storyline but at the same time I wanted to give another turning point to my female character with the purpose to change the reality of the original event told by my friend.

6) What is a noir and what makes this book Puerto Rican noir, besides it taking place in San Juan? What is Puerto Rico’s contribution to noir literature?

The setting of all the presented stories is San Juan and together with the characters they reflect part of our culture. The rituals, the streets, the hotels backstage, the different type of living styles of Puerto Ricans are shown on the plots. Daily we hear about situations in the TV news or we read articles on newspapers that can be the perfect material to create these kinds of stories or novels. Sergio Ramírez said, “The dark novel transforms itself in a vehicle to tell us how the countries in which we live are”. The noir is present wherever humanity is. Besides the dark environments in which the story develops, the term noir is said to come from Série Noire by the French publishing house Gallimard, also from the magazine Black Mask published in the USA. The human passions and the curiosity to know the truth are the building blocks for this type of text. In Puerto Rico the theme of noir novel had been studied by Paul Di Paolo Harrison in his book, Noir boricua: La novela negra en Puerto Rico (Isla Negra Editores, 2016). The author studies a variety of Puerto Rican authors and their novels. He also explores the island social problems as the illegal immigrant traffic, the drug traffic, the racial discrimination, the colonial relationship with USA, the sexual abuse, and other themes related to the noir. In other book, El cuerpo del delito, el delito del cuerpo: la literatura policial de Edgar Allan Poe, Juan Carlos Onetti y Wilfredo Mattos Cintrón (Ediciones Callejón, 2012), José Ángel Rosado theorizes that the roots of the noir novel in Puerto Rico originated from the government oppression due to our colonial relationship with USA.

7) What are your literary projects right now? Or are they all on stand by? How do you manage your time?

I’m working on a new short story collection about the Puerto Rican future. Also I’m rewriting a saga that I started ten years ago, and giving the final touches to a young adult novel. I have to squeeze all these efforts between my family and clinical time. I usually write on weekends and nights, my double personality, physician during the day and writer at nights. But you can imagine that ideas come at any time and place. From time to time I visit schools to offer workshops on creative writing for children and adolescents. One of those workshops is about bullying based on my young adult novel, P.A.M.

Also, I had the opportunity to talk about the environment with two of my books: Stories of the Puerto Rican Fauna (2002), and Cielo, mar y tierra (2003). Another thing that I enjoy is visiting the universities to discuss my novels, at this time on a tour with Azábara (Isla Negra, 2015), a novel about a sinking island with many parallels with Hurricane María and the sociopolitical situation of Puerto Rico.

8) Let’s return again to the situation in Puerto Rico. What can we as writers do to help Puerto Rico today?

As writers we should become the memory of our countries. Anton Chekhov once said that writers should signal at the problems but it is not their responsibility to solve them. With our words we can create a text in which citizens could recognize themselves and think about some issues. By means of our literary works we perform a biopsy of our time with all our virtues and defects. As writers we must get closer to the people who want to know about writing. As a student in high school I wanted to bring a known writer to my Spanish class. I tried by all the possible means to find him. Finally, I called the author but it was impossible to have him at school, because he was charging $100.00 dollars for the visit, in the 80s this was an astronomical quantity for me. Since that experience, I thought that if I could become a writer, I would give a new end to that story if another kid or teacher called me. The direct contact with teachers and student is life changing. The solitude in this kind of art is supported at the moment of writing, but is forgotten at the time of departing with the readers.

9) Do you have a message to Puerto Rico at this time?

Puerto Rico, believe in you as a nation. Don’t be afraid of liberty. Thanks for your solidarity.

Finally, I want to say Gracias, Jose, Gracias Puerto Rico.

José Rabelo(1963, Aibonito, Puerto Rico). Escritor y dermatólogo. Cursó sus estudios en los recintos de Cayey y Ciencias Médicas de la Universidad de Puerto Rico. Entre sus publicaciones se destacan: las novelas Los sueños ajenos (Isla Negra Editores, 2011) y Cartas a Datovia (Isla Negra Editores, 2010, premiada por el PEN Club de PR); y los cuentos Esquelares (Isla Negra Editores, 2012); Azábara ( Isla Negra Editores, 2015). Su relato “Kadogo” fue premiado en el Certamen de Cuento 2014 de El Nuevo Día y publicado en la antología Latitud 18.5 (País Invisible Editores, 2014). Entre sus textos de literatura infantil y juvenil se destacan: Cielo, mar y tierra (Ediciones payaLILA, 2003, Premio Nacional de Cuento Infantil del PEN Club de PR) y P.A.M. (Publicaciones Educativas, 2013, novela premiada por el PEN Club de PR); y Club de calamidades (Ediciones SM, 2014, Premio El Barco de Vapor). Actualmente imparte clases en la Maestría en Creación Literaria de la Universidad del Sagrado Corazón.

Jhon Sánchez: A native of Colombia, Mr. Sánchez arrived to the United States seeking political asylum. Currently, a New York attorney, he’s a JD/MFA graduate. His publications in 2017 are available in Caveat Lector, 34thParallel, Swamp Ape Review, Caveat-Lector, Foliate Oak Literary Magazine, Newfound, Gemini Magazine and Midway Journal. His work has been nominated for The Best of the Net 2016 and for a Pushcart Prize in 2015 and 2016. He was also awarded the Newnan Art Rez Program for summer of 2017.

Special thanks to Adam Jaslikowski and Holly Rice for their editorial comments and please check Holly’s latest publication, ‘O’ is available in Matrix Magazine, the Americanadian issue.