By Richard Falk

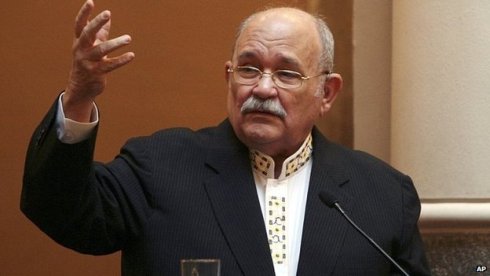

What follows is the modified transcript of a talk given at Fordham University School of Law [24 Oct] honoring the memory of the recently deceased Maryknoll priest, Father Miguel d’Escoto, who had been both the Foreign Minister of Sandinista Nicaragua and President of the UN General Assembly, as well as pastor to the poor in the spirit of Pope Francis, an extraordinary person who fused a practical engagement in the world with a deeply spiritual nature that affected all who were privileged to know and work with him.

It is a humbling honor to speak at this gathering of remembrance dedicated to a truly great human being who inspired and touched the lives and activities of so many of us in this room. Kevin Cahill is among those here who had such an intimate and sustained friendship with Father Miguel. Kevin is also a person with his own abundant inspirational gifts, and I remain deeply grateful to him for originally bringing me into contact with Miguel.

Others here today could assuredly speak more knowingly about the person. I will only offer this personal observation: Miguel exhibited a remarkable quality of moral radiance that was immediately apparent to all those fortunate enough to cross his path. The only person in my experience who possessed a comparable depth of ethical being was Nelson Mandela with whom I had a single and brief, yet memorable, encounter.

The title given to my remarks is something I admit imposing upon myself, and now at this moment of delivery strikes me now as far too ambitious. I chose such a theme because it does reflect the most enduring and empowering dimension of my association with Miguel, and seemed appropriate to reflect upon in the venerable academic venue of the Fordham School of Law.

My point of departure is this: if we believe, which many do not, that justice is the proper end of law, then we must struggle to overcome the calculative or transactional mentality that dominates our legal culture, restricting our attitudes and endeavors involving law to the domain of the feasible. I am fully aware that I am endorsing an unconventional outlook by elevating the moral imagination and what I would call ‘utopian realism.’ This kind of formulation disregards the conventional understanding of law as essentially offering a suite of techniques for problem-solving that presupposes a view of politics as ‘the art of the possible.’

It is this kind of ethical radicalism that made the life of Father Miguel so exemplary, and in the best sense, ‘revolutionary,’ for all those whose lives he affected whether in ministering to the poor or challenging the high and mighty, whether acting in a pastoral capacity or as a man of the world. It is important to appreciate that Miguel was both an ardent Nicaraguan nationalist and a passionate citizen of the world, what I call a ‘citizen pilgrim,’ embarked on a pilgrimage to a global future that embodies peace with justice.

Let me preface this inquiry into the spiritual sources of legal creativity with a general remark that pertains particularly to international law. I may be almost alone among law professors in believing that that international law is the field of law that is most relevant to the ultimate survival of the human species. The sad reality is that international law continues to struggle for survival as a field of study, being often denigrated, evaded, and violated by the most powerful governments on the planet whenever law is seen as blocking a preferred policy and there are always many apologists among the ranks of legal experts and diplomats ready to offer a comforting rationalization.

And yet viewed from a perspective other than war/peace and security, international law in relation to trade and investment has basically served to protect the interests of the rich and powerful, while shackling the poor and vulnerable. In other words, international law has this dual face: it bends to the geopolitical will of the militarily powerful while often cruelly imposing accountability on the weak. At the founding of the UN a Mexican diplomat caustically observed that ‘we have created an organization that regulates the mice while the tigers roam freely.’ And so it is.

It is against this background that Miguel d’Escoto’s spiritual wisdom creates a contrast with business as usual in the world of real politik. Even for most global reformers, the criterion for constructive action is a realistic appreciation of achievable limits, what I would identify as horizons of feasibility. We are living increasingly in a world in which there are growing gaps between what is feasible and what is necessary, what I identify as horizons of necessity. Adapting to climate change in the Age of Trump underscores this menacing gap between feasibility and necessity. As a diplomat Father Miguel was almost unconcerned with feasibility as conventionally understood if it stood in the way of necessity or desirability. He was deeply sensitive to the imperatives of necessity, and even more so to the moral and spiritual imperatives of doing what is right under a particular set of circumstances, and for this reason alone he was most responsive to what I identify here as horizons of spirituality.

He was motivated by a belief, undoubtedly reflecting his religious faith, in the potency of right reason, and on this basis conceived of international law as a crucial vehicle for realizing such a vision, embracing with moral enthusiasm a kind of ‘politics of impossibility’ in which considerations of justice outweighed calculations of feasibility or the obstacles associated with geopolitics. It is with an awareness of the trials and tribulation of Nicaragua and its long suffering population that Father Miguel turned to law as an imaginative means of empowerment.

Let me illustrate by reference to the historic case that Nicaragua brought against the United States in the early 1980s at the International Court of Justice in The Hague. It was a daring legal flight of moral fancy to suppose that tiny and beleaguered Nicaragua could shift its struggle from the bloody battlefields of U.S. armed intervention and a mercenary insurgency against the Sandinista Government of which he was then Foreign Minister to the lofty legal terrain that itself had been originally crafted to reflect the values and interests of dominant states, the geopolitical players on the global stage. But more than this it was a brilliant leap of political imagination to envision the soft power of law neutralizing the hard power of high tech weaponry in a high stakes ideological struggle being waged in the midst of the Cold War.

Such an attempt to shift the balance of forces in an ongoing conflict by recourse to international law and the World Court had never before been made in any serious way. It was a David and Goliath challenge that the World Court as the highest judicial institution in the UN System had yet to face in a war/peace context, and it turned out to be a test of the integrity of the institution.

Let me recall the situation in Nicaragua briefly. The United States was supporting a right-wing insurgency, the counterrevolutionary remnant of the Somoza dictatorship, a single family that had cruelly and corruptly ruled Nicaragua between 1936 and 1974 on behalf of corporate America (the era of ‘banana republics’), leaving the country in impoverished ruins when the Somoza dynasty finally collapsed. The Somoza-oriented insurgents were known as the Contras, and were called ‘freedom fighters’ by their American sponsors and paymaster because they were opposing the Sandinista Government that had won a war of national liberation in 1979, but was accused by its detractors of leftist tendencies and Soviet sympathies, which was the right-wing ideological way of obscuring the true affinity of the Sandinista leadership with the teachings of Liberation Theology rather than with the secular dogmatics of Marxism. It was a way of depriving the people of Nicaragua of their inalienable right of self-determination. The United States Government via the CIA was training and equipping the Contras, and quite overtly committing acts of war by mining and blockading Managua, Nicaragua’s main harbor and its lifeline to the world.

It was these interventionary undertakings that flouted the authority of international law and the UN Charter. Father Miguel’s addressed the UN General Assembly in his capacity as Nicaragua’s acting Foreign Minister, vividly describing the conflict with some well-chosen provocative words: “It is obvious that the war to which Nicaragua is being subjected is a U.S. war, and the so-called Contras are merely hired hands serving the diabolical objectives of the Reagan Administration.” Later in the same speech he condemned the U.S. Government for recently appropriating an additional $100 million “to finance genocide against our people.” [Address to UNGA, Nov. 3, 1986]

I quote this robust language partly to show that Father Miguel’s spiritual nature did not always mean a gentle demeanor or denote the absence of a fighting spirit. As here, when deemed appropriate to the situation, Miguel readily relied on undiplomatic candor to get his point across. He was also insistent on using such occasions to talk truth to power and to lay blame and responsibility for the torment of the Nicaraguan people where it belonged, however impolitic it was to do so.

Without going into the details of the case, it was possible for Nicaragua to lodge such a complaint against the United States because U.S. Government had earlier agreed to accept the authority of the ICJ if the other side in an international conflict had been similarly committed. With this awareness, Father Miguel in his role as Foreign Minister (1979-90) realized two things: that the sovereign rights of Nicaragua were being overridden in a manner in flagrant violation of international law and that the World Court was supposed to provide countries with a nonviolent option of resolving international legal disputes, seen as an important contribution to maintaining world peace that the U.S. had itself strongly championed throughout most of the 20th century.

It may not seem so unusual for a small country to take advantage of a potential judicial remedy, but in fact it had never happened—no small state had ever gone to the World Court to protect itself against such military intervention, and to do so on behalf of a progressive government in the Third World in the midst of the Cold War seemed to many at the time like a waste of time and money that Nicaragua could ill afford.

It is here where one begins to grasp this potentially revolutionary idea of relying upon the spiritual sources of legal creativity. Father Miguel was convinced that what the United States Government was doing was legally and morally wrong, and that it was an opportune time for the mice to fight back against the predator tiger. It was an apt occasion to act by reference to horizons of spirituality.

Yet this did not mean that Miguel would ignore the pragmatic dimensions of effectiveness. Nicaragua managed to persuade Harvard law professor, Abram Chayes, to act on their behalf as head legal counsel. This was a brilliant tactical move that I applauded at the time (even though it meant that as Nicaragua’s second choice I lost out). Aside from being a first-class international lawyer with a high global profile, Chayes had previously served as John F. Kennedy’s Legal Advisor and close confidant at the time of the Cuban Missile Crisis. The symbolism could not have been more pointed, underlining the fact that Chayes was committed to upholding international law rather than being a combatant in the ideological sideshow carried on throughout the Cold War. Not surprisingly, the Wall Street Journal audaciously described Chayes as ‘a traitor’ for accepting such a role.

I had the opportunity to work with Chayes and Father Miguel in the American Irish Historical Society here in Manhattan that was operating under the benign tutelage of none other than Dr. Kevin Cahill. We worked hard for several days as a team developing the arguments both as to the authority of the ICJ to adjudicate, what we lawyers call ‘jurisdiction,’ to be decided in a separate preliminary decision, as well as on the substance of Nicaragua’s allegations, which constituted the second phase of the litigation. What was so impressive to me then, and even now, almost 40 years later, is that this effort to combine a somewhat utopian motivated legal undertaking with a practical mastery of the technical dimensions of the case illustrated for me the extraordinary blending of spiritually grounded, yet worldly wisdom with the down to earth skills of legal craft.

The outcome of the Nicaragua narrative is too complicated to describe properly, but in short—counsel for Nicaragua persuaded the Court that it had jurisdictional authority, at which point the United States petulantly, yet not unexpectedly, withdrew from the proceedings correctly realizing that if it could not prevail at this jurisdictional phase it had virtually no chance to have its legal arguments accepted at the merits phase of the case. Further, the U.S. Government was so displeased with the ICJ that it seized the occasion to renounce its earlier formal acceptance of what is technically referred to as ‘compulsory jurisdiction,’ which meant that no state could commence such an action against the USG in the future, and that the U.S. was itself permanently foreclosed from proceeding against a state against which it had legal grievances unless that state gave its consent.

This retreat from adjudicating international legal disputes has been an unintended and unfortunate lasting effect of the Nicaragua case. The American stance of viewing international law as only viable when it supports its geopolitical tactics has sent a damaging message to the world. It has definitely weakened the role and potential of the ICJ and of international judicial authority generally. In one sense, the US withdrawal was understandable for those who are driven to shape foreign policy by feasibility calculations rather than by certain abiding values such as, here, adhering to the rule of law. It hardly required a legal genius in the State Department to anticipate that if the Court upheld its legal authority to pronounce upon the controversy, then it would almost certainly rule in favor of Nicaragua on the substantive issues. Despite some technical issues involving the selection of the applicable legal authority, given the sweeping prohibitions of international law and the UN Charter against uses of force except in situations of self-defense against a prior armed attack, the pro-Nicaragua outcome was entirely predictable.

What was rather intriguing from a jurisprudential point of view was that despite its much hyped boycott of the proceedings and accompanying denunciation of the jurisdictional finding, the U.S. in the end quietly complied with the principal finding in The Hague, namely, that the naval blockade of Nicaragua’s harbors was unlawful. As would be expected, the USG never acknowledged that it was complying, nor did Nicaragua dance in the streets of Managua, but the cause/effect relationship between the judicial decision and compliant behavior was clear to any close observer.

There was then some reality to the expression ‘the force of law,’ and the USG, even during the Reagan presidency, did not want to stand before the world as openly defying the law, even international law. Such an assessment may have reflected the fact that the U.S. Government was in the midst of a struggle to win the legitimacy war being waged against the Soviet Union, which partly hinged on the relative reputation of these two dueling superpowers in relation to respect for international law and human rights, signature issues of ‘the free world.’

For me this Nicaragua experience was a compelling example of Father Miguel’s achievements that followed directly from his deep commitment to the horizons of spirituality and decency. It was far from the only instance. Let me mention two others very quickly. One of my other connections with Father Miguel was to serve as one of his Special Advisors during his year as President of the UN General Assembly thoughout its 63rd session, 2008-09. As continues to be the case, life could become difficult for any leading UN official who openly opposed Israel. Father Miguel was deeply aware of the Palestinian ordeal and unabashedly supportive of my contested role as Special Rapporteur for Occupied Palestine on behalf of the Human Rights Council in Geneva. When I was detained in an Israeli prison and then expelled from Israel at the end of 2008, Father Miguel wanted to organize a press conference in NYC to give me an opportunity to explain what had happened and defend my position. I declined his initiative, perhaps unadvisedly, as I didn’t want to place Miguel in the line of fire sure to follow.

At the end of 2008 Israel launched a massive attack against Gaza, known as Cast Lead, and Father Miguel sought to have the General Assembly condemn the attack and call for an immediate ceasefire and Israeli withdrawal. It was a difficult moment for Father Miguel, feeling certain that this was the legally and morally the right thing to do. Yet as events proceeded and diplomatic positions were disclosed, Miguel was forced to recognize that the logic of geopolitics worked differently, in fact so starkly differently that even the diplomat representing the Palestinian Authority at the UN intervened to support a milder reaction than what Miguel deemed appropriate. Unlike his Nicaraguan experience, here the backers of feasibility prevailed, but in a manner that Father Miguel could never reconcile himself to accept.

I met many diplomats at UN Headquarters here in NY who said that no one had ever occupied a high position at the UN with Father Miguel’s manifest quality as someone so passionately dedicated to righteous principle. Pondering this, it occurred to me that one possible exception was Dag Hammarskjöld, an early outstanding UN Secretary General, who died in a plane crash, apparently assassinated in 1961 for his principled, yet geopolitically inconvenient, dedication to peace and justice. From his private writings we know that Hammarskjöld’s UN efforts also sprung from wellsprings of spirituality.

Most GA presidents take the post as an honorific feather in their cap, the symbolic culmination of a public sector career, and spend the year presiding over numerous tedious meetings and hosting an endless series of afternoon receptions, but never make any effort to influence, much less enhance, the role of the General Assembly or otherwise strengthen the UN as an institution of potential global governance. Miguel, in contrast worked tirelessly to make the UN more effective, more respectful of law, more democratic, and above all, more sensitive to claims reflective of global justice.

Miguel took full advantage of his term as president of the General Assembly to provide venues within the Organization that offered humane alternatives to neoliberal economic globalization. He sponsored and organized meetings at the UN designed to overcome current patterns of economic and ecological injustice, making use of the presence in New York City of such non-mainstream economists as Jeffrey Sachs and Joseph Stiglitz, and the prominent Canadian activist author, Maude Barlow. Here again Father Miguel demonstrated his grounded spirituality by once more combining the visionary with the practical.

I had the opportunity to work with Father Miguel on several proposals to raise the profile and role of the General Assembly as the most representative and democratic organ of the UN. This initiative was rather strategic and partly meant to counter the US-led campaign to concentrate UN authority in Security Council so that Third World aspirations and demands could be effectively thwarted, and the primacy of geopolitics reestablished after the assault mounted in the 1970s by the then ascendant Nonaligned Movement.

What I have tried to describe is this deep bond in the life and work of Father Miguel between the spirituality of his character and motivations and the practicality of his involvement in what the German philosopher, Habermas, calls ‘the lifeworld.’ I find it indicative of Father Miguel’s deep spiritual identity that he suffered a punitive response to his life’s work from the institution he loved and dedicated his life to serving, being suspended in 1985 by Pope John Paul II from the priesthood because of his involvement in the Nicaraguan Revolution. Miguel was reinstated 29 years later by Pope Francis, who many view as a kindred spirit to Miguel.

There is an object lesson here for all of us: in a political crisis the moral imperative of service to people and ideals deserves precedence over blind obedience to even a cherished and hallowed institution. This would undoubtedly almost always pose a difficult and painful choice, but it was one that defined Father Miguel d’Escoto at the core of his being, which he expressed over and over by doing the right thing in a spirit of love and humility, but also in a manner that left no one doubting his firmness, his affinities and commitments, as well as his unwavering and abiding convictions.

As I suggested at the outset, the daring and creativity that Father Miguel brought to the law and to his work at the UN sprung from spiritual roots that were deeply rooted in both religious tradition and in an unshakable solidarity with those among us who are poor, vulnerable, oppressed, and victimized. For Miguel spirituality did not primarily equate with peace, but rather with justice and an accompanying uncompromising and lifelong struggle on behalf of what was right and righteous in every social context, whether personal or global.

There is no assurance that this way of believing and acting will control every development in the world or even control the ultimate destiny of the human species. Humanity retains the freedom to fail, which could mean extinction in the foreseeable future.The happy ending of the Nicaragua case needs to be balanced against the prolonged and tragic ordeal of the Palestinian people for which there is still no end in sight. Beyond wins and losses, what I think should be clear is that unless many more of us become attentive to the horizons of spirituality and necessity the outlook for the human future is presently bleak. Father Miguel d’Escoto’s disavowal of the domain of the feasible is assuredly not the only way to serve humanity, but it is a most inspiring way, and points us all in a direction that is underrepresented in the operations of government and public institutions, not to mention during the speculative frenzies on Wall Street and the backrooms of hedge fund offices.

In my language, Father Miguel d’Escoto was one of the great citizen pilgrims of our time. His life was a continuous journey toward what St. Paul called ‘a better city, a heavenly city’ to manage and shape all life on Planet Earth.

Richard Falk is a member of the TRANSCEND Network, an international relations scholar, professor emeritus of international law at Princeton University, author, co-author or editor of 40 books, and a speaker and activist on world affairs. In 2008, the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) appointed Falk to a six-year term as a United Nations Special Rapporteur on “the situation of human rights in the Palestinian territories occupied since 1967.” Since 2002 he has lived in Santa Barbara, California, and taught at the local campus of the University of California in Global and International Studies, and since 2005 chaired the Board of the Nuclear Age Peace Foundation. His most recent book is Achieving Human Rights (2009).