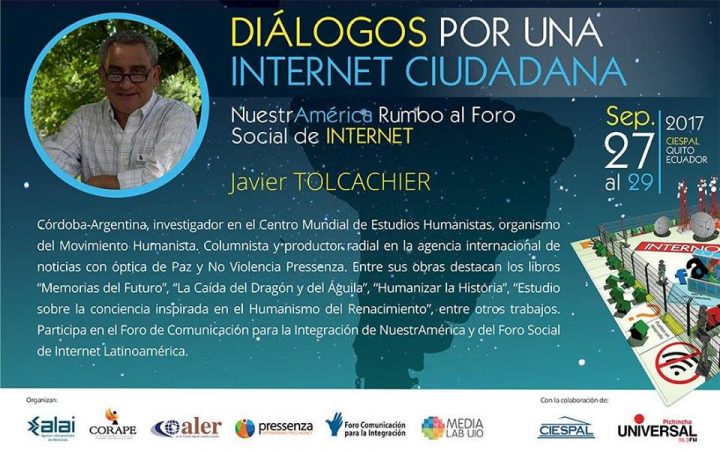

Within the framework of the “Dialogues for a Citizen Internet”, a series of conferences that discussed the current monopoly orientation of the Internet, Javier Tolcachier, a researcher at the Centre for Humanist Studies, developed the subject of “cyber weapons”. The conference, organized by Latin American communication collectives (ALAI, ALER, Pressenza, Corape, together with Media Lab and the Communication Forum for the Integration of Latin America), took place between the 27th and 29th of September at the headquarters of the International Centre for Higher Communication Studies for Latin America (CIESPAL) in Quito, Ecuador.

We publish here the paper in its entirety.

In 1942, science fiction writer Isaac Asimov in his story Run Around, announced what would come to be known as “the 3 laws of robotics”. His first statement – pre-eminent over the next two – states: “A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.” The humanist visionary predicted in that brief tale how robotics could be used in the future to carry out tasks in environments that are dangerous to human beings, and he clearly envisioned the problems that could arise in the relationship between automatons and unknown, unforeseen or unpredictable circumstances.

Also in Japan, Osamu Tezuka, father of the modern Japanese comic, formulated “Ten Principles of Robot Law” for his series AstroBoy, the two initial sentences of which indicated that robots should serve humans and that a robot should never kill or wound a human being.

The series, whose main character is an android child, would become the animation predecessor of the modern anime genre. It started to be drawn in the 1950s and is a reflection of the traumatic conditions from which Japanese society emerged after the nuclear detonations and widespread destruction of the Second World War.

Although the Briton Alan Turing had already proposed the possibility of intelligent machines, it was in 1956 when mathematician and programmer John McCarthy coined the concept “artificial intelligence”, giving rise, together with another computer pioneer, Marvin Minsky, to the first AI laboratory at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Its purpose was to create and programme machines that could learn like a human being. We will seek to make machines, said McCarthy, “use language, form abstractions and concepts, solve kinds of problems now reserved for humans, and improve themselves.” In the same year, International Business Machines (IBM) launched its first computer, the “701”, designed by another Dartmouth workshop participant, Nathaniel Rochester. Subsequently, as the industry increasingly incorporated automation and computing was expanded and perfected, artificial intelligence, among promoters and critics, victories and defeats – added procedures to its repertoire.

Games were a prolific field of experimentation for the new discipline, among them backgammon, chess and go, games where strategy and combinations pose an impressive number of possible variants, precisely an important part of the scenarios problematized by AI. Already by 1979, a programme could defeat world backgammon champion Luigi Vila, while in 1997, Russian chess player Gary Kasparov was beaten by the Deep Blue supercomputer. In 2016, AlphaGo, the programme developed by DeepMind – founded in 2010 and now owned by Google – defeated Korean master Lee Sedol, the winner of 18 world titles.

Videogames were also an area of experimentation for AI companies: a space dangerously close to battle and war. In the recent Dota 2 international video game tournament, an OpenAI robot beat professional player Danylo “Dendi” Ishutin.

Open AI was founded by Elon Musk (Tesla, Space X, DeepMind) in collaboration with Sam Altman (Y Combinator) and is, according to its own definition, “a non-profit artificial intelligence research company” that works in free collaboration with other institutions in patents and open research. For Musk, aware of the potentials of AI, the best defence against the potential risks of AI is to “empower as many people as possible to have AI. If everyone has AI powers, then there’s not any one person or a small set of individuals who can have AI superpower.” Interestingly, this is also the latest message from Google and Microsoft, for whom “democratising access” means massively multiplying a technology to increase their economic profits and power in the field.

AI has already made many advances in the fields of learning, facial recognition, language, optical identification, preventative diagnosis of diseases, communication, home automation, unmanned transport, industrial and domestic robotics and a large number of applications and computer systems in the most diverse fields.

But at the same time, in the hypermilitarist environment of the United States, different projects for the military use of semi-autonomous weapons began to develop at an early stage. In the 1980s, the US Navy installed the MK 15 Phalanx Close-In Weapons System, built by Raytheon, on its ships, which detects missiles or threatening aircraft and responds with machine guns. According to the firm, 890 such systems were built and used by the naval forces of 25 countries. Similar models such as Counter Rocket, Artillery, and Mortar System (C-RAM) (manufactured by Northrop Grumman) were installed on land in 2005 in Iraq. Systems to repel attacks of this type were also developed by Israel (Iron Dome) and Germany (NBS Mantis) who used them in Afghanistan.

Back in 1991, in the course of the Gulf War, the US military used the Dynamic Analysis and Replantation Tool (DART), developed on the basis of artificial intelligence to solve supply, personnel and logistics problems.

For war planners, the aim has long been obvious: to perfect mortal machinery by transferring the maximum amount of responsibility to sophisticated technologies. For this purpose, artificial intelligence is an essential branch of research and application.

The state of play on the issue of lethal autonomous weaponry

First of all, it’s necessary to specify that there are weapons with different types of autonomy, all of which fall into the category of “killer robots”. According to Human Rights Watch’s “Losing Humanity” report, there is still no weapon with total autonomy, but technology is pointing in that direction and there are prototypes in use.

As for the intermediate forms of autonomy, in addition to those already indicated for automatic response, there are surveillance weapons with monitored fire capacity, such as SGR-1s, installed by South Korea along the demilitarized zone with North Korea or Sentry Tech and Gardium (of the G-NIUS company), placed by the Israeli armed forces on the border with Gaza. Finally, there is the relative autonomy armament remotely operated such as the deadly drones of the US, Predator and Reaper, which have caused countless casualties in Pakistan, Somalia, Yemen, Afghanistan and Iraq.

The United States, while notorious promoters of the use of AI weaponry, are not the only ones to develop this technical barbarity. In 2013, Great Britain made a test flight of a prototype of its unmanned, autonomous Taranis fighter plane (BAE Systems) capable of carrying bombs or missiles and of mid-air refuelling, without remote intervention. Similar prototypes have been developed by France (nEUROn, Dassault Aviation), Germany/Spain (Barracuda, EADS), Russia (Skat, MIG), Israel (Harpy) and the USA (X-45, Boeing and X-47B, Northrop Grumman). Even India has started a similar project (Aura, DRDO).

There already exists a large arsenal of vehicles, tanks, bombs, monitoring systems, cargo and combat robots, ships and submarines, whose use of different aspects of AI clearly shows a direction towards greater autonomy.

In guidelines from the Research and Engineering division of the US Defence Department in May 2014, it is stated that the technologies associated with autonomy are multiplying: from sensors capable of understanding the surrounding environment to programmes with algorithms that can make decisions or seek human assistance. Through autonomy, we should be able to reduce the number of personnel required to perform missions safely.

Similarly, in the COI roadmap, Autonomy (one of the seventeen subject matter “communities of interest” into which the Department of Defence has divided its military-technological development projects) shows a three-phase projection that, passing through a stage of totally autonomous air combat squadrons, culminates in a scalable coupling of autonomous systems. The medium-term goal is to achieve integrated systems (Tactical Battle Manager (TBM)) to support combined operations of different types of autonomous armed vehicles in enemy areas.

The Stock Exchange or Life

Another motivation for the exploitation of AI for military purposes – perhaps the main one – is profit. Emerging technologies are a source of huge business in general and corporations of the military-industrial complex do not want to be left out.

Tractica Consultancy forecasts that “the robotics market will experience strong growth between 2016 and 2022 with revenue from unit sales (excluding support services such as installation and integration) of industrial and non-industrial robots growing from $31 billion in 2016 to $237.3 billion by 2022. Most of this growth will be driven by non-industrial robots, which includes segments like consumer, enterprise, healthcare, military, UAVs, and autonomous vehicles.”

For all these reasons, there are huge investments in AI development, mainly by large IT companies, through the purchase of dedicated companies. Fifty such companies were sold in 2016, eleven for amounts greater than 500 million dollars. Major buyers include Alphabet/Google, Apple, Amazon, IBM and Microsoft. China, for its part, plans to grow its AI industry from 22 billion in 2020 to 150 billion in 2030.

In particular, the market for military robotics will jump from the current 16.8 billion in 2017 to 30.83 billion dollars by 2022, in just five years. The expectation is that military spending on robotics will triple between 2010 and 2025.

The profits of the major aerospace companies, all of them involved in military-use projects with a high AI component, speak for themselves. According to 2015 data, Boeing made more than $96 billion in sales, Airbus, now EADS, almost 72 billion; Lockheed Martin, 46 billion; General Dynamics, 31.5 billion; followed by United Technology, BAE Aviation, GE Aviation and Raytheon with revenues between $23 billion and $28 billion. According to analysis by consulting firm Deloite, the Defence subsector is expanding as civil aviation earnings growth slows.

Other relevant actors in the robotic weapons market are iRobot Corp., Allen-Vanguard Corporation, Honeywell Aerospace, GeckoSystems Intl. Corp., Honda Motor Co. Ltd., Bluefin Robotic Corp., AB Electrolux, Deep Ocean Engineering Inc., ECA Hytec SA, McArtney Group, Fujitsu Ltd., Toyota Motor Corp., AeroVironment, Kongsberg Gruppen, Saab AB, Elbit System Ltd., and Thales Group (France), among others.

As for potential buyers, reports estimate that 10% will go to North America, 20% to Europe, 40% to Asia-Pacific and 50% to the rest of the world, a portion that will primarily go to Middle East countries.

Prospects indicate that most countries are willing to acquire drones, autonomous land vehicles and patrol and espionage robots, among other weapons. In this way, an arms race is imminent in this sense, due to the destabilization that is provoked (and fuelled) by every technological innovation in the military. This precludes the possibility that the use of AI for military purposes will contribute, at least in the short term, to reducing defence budgets.

Robots that annihilate human lives

Advocate-lobbyists of military robots say their use will reduce the number of victims. They point out that fewer troops directly involved in battle will result in fewer deaths. Summoning war scenarios between machines, they indicate that even civilian casualties would be smaller due to the greater precision of weapons equipped with high-tech tracking and detection.

This is of course a fallacy. The thousands of deaths from the bombing of American drones in Afghanistan, Iraq, Yemen, Somalia and Pakistan are painful and sufficient proof of this. According to the Pakistani daily Dawn News (quoted by Red Voltaire), “For every suspected al-Qaida or Taliban member killed by missiles fired from US drones, 140 innocent Pakistanis also had to die. More than 90 percent of those killed in the deadly missile attacks were civilians, the authorities say.” Along the same lines, the 2014 report by the humanitarian Human Rights organisation, Reprieve, indicates that for each intentional target, US remote-controlled bombers killed twenty-eight civilians.

As for military casualties, at present, the deadly robots serve only one side, which can effectively reduce their deaths, not their enemies’. This kind of “remote combat” allows attackers the possibility of multiple wars simultaneously and anaesthetizes their own populations to their devastating effects.

The suffering, outrage and helplessness generated on the ground by attacks with these weapons only fuels the desire for revenge in the populations that have been assaulted, sowing a new wave of terror and endless violence.

AI technology weapons effectively make it easier to destroy the infrastructure of the attacked country, making local development more difficult, creating conditions for social exclusion that fuel the spiral of war with new cohorts of unemployed.

On the other hand, robotics will not only be used for war, but also to increase the possibilities of surveillance and patrolling, including as support or replacement of police forces and private security forces. Supported by the advantage of its permanent presence (24/7) the massive control effects on the entire population are evident. On the other hand, the power of autonomy will expand the possibility for human rights violations without any accountability. This is, of course, intolerable.

A different future

In the face of these scenarios and horizons, the clamour from scientists, academics, investors and the precursors of AI to outlaw the use of this technology for military purposes has already begun to be heard.

Prior to the recent International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI 2017) in Melbourne, 116 founders of robotics and AI companies called on the United Nations to ban LAWS (Lethal Autonomous Weapons Systems) in an open letter.

The signatories of the letter point out that “lethal autonomous weapons threaten to become the third revolution in warfare. Once developed, they will permit armed conflict to be fought at a scale greater than ever, and at timescales faster than humans can comprehend. These can be weapons of terror, weapons that despots and terrorists use against innocent populations, and weapons hacked to behave in undesirable ways. We do not have long to act. Once this Pandora’s Box is opened, it will be hard to close.”

Back in December 2016 – says the Future of Life Institute – 123 member countries of the International Convention on Conventional Weapons agreed unanimously to begin formal discussions on autonomous weapons and 19 nations have already declared their prohibition. Various civil society organizations such as Human Rights Watch, the Campaign to Stop Killer Robots, the International Campaign to Ban Landmines (ICBL), Mines Advisory Group (MAG), Walther-Schücking-Institut für Internationales Recht, and the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF) participated in the pre-conference work, as well as signatory countries to the Convention and observers.

During the Fifth Review Conference of the Convention, it was decided to establish a group of governmental experts (GGE) to first meet in April or August and then again in November 2017. The first session was cancelled due to budgetary difficulties, so now the eyes and actions of the Stop Killer Robots campaign are on the meeting to be held in November.

In his April 2013 report, the United Nations High Commissioner on extrajudicial, arbitrary and summary executions, Christof Heyns, pointed out that even when government officials assert that the use of autonomous weapons is not foreseen at the moment, ” Subsequent experience shows that when technology that provides a perceived advantage over an adversary is available, initial intentions are often cast aside.” A little further on, the diplomat says, “If the international legal framework has to be reinforced against the pressures of the future, this must be done while it is still possible.”

And this is precisely what activist alliances are calling for, demanding:

- A ban on the development and use of fully autonomous weapons through a binding international treaty.

- The adoption of national laws and policies prohibiting the development, production and use of fully autonomous weapons.

- The revision of technologies and components that could lead to the development of autonomous weapons.

As far as we’re concerned, we would add that in addition to the legally binding prohibition, what we have to achieve is a change in mental direction.

Artificial intelligence will continue to advance, but it will only be able to help to solve human problems if human intelligence advances. A weapon is never intelligent, a war is never intelligent, whether it is supported by autonomous technology or not.

We aren’t talking about, nor is it possible to stop knowledge or science, since these are inherent in human history. Preventing the destructive action of governments and business corporations is certainly necessary but only part of the puzzle. Something must also change in our interiority, in the way human groups see life.

Robots will never reach the level of human intelligence for one simple reason: we are also developing beings. We advance by learning from our successes and also – although sometimes it doesn’t seem so – from our mistakes. And above all, we are beings that evolve – slowly but with the persistence of millennia – towards a new kind of humanity, kind, empathetic and compassionate, virtues that are difficult to grasp by algorithms.

As evidence of this evolution, and as a further step towards the end of all wars and weapons, let us ban robotic weapons.