Finally, after decades of post-independence dictatorships, the shameful rigging of presidential elections, and post-election violence in 2007 that led to 1200 people slaughtered and hundreds of thousands of internally displaced refugees, Kenya can hold its head high and say it now knows how to run a transparent election.

Let’s be careful. We’re not saying it was 100% free and fair, but in terms of the process for registering voters and counting the votes on the 8th of August we can say it was transparent.

A transparent election is not easy to manipulate and what this election had was a transparent end-to-end process that ensured that the votes counted and announced in the polling stations, the results agreed by the party representatives in all 40,883 polling stations, those written down on special forms (34A) and then signed by all those concerned and stamped by the representative of the Independent Electoral and Boundary Commission who oversaw the process, are the same results that then started to appear on the IEBC website in the hours after the voting finished and counting started to happen.

Not all the results are in on the website, but we can be a little bit forgiving. Some of the places that haven’t yet had their forms uploaded are in the most remote corners of Kenya with terrible infrastructure in terms of electricity, roads and telephone network connection. A little over 30 of the 40883 forms are not yet on the website. Kenya can still congratulate itself for this.

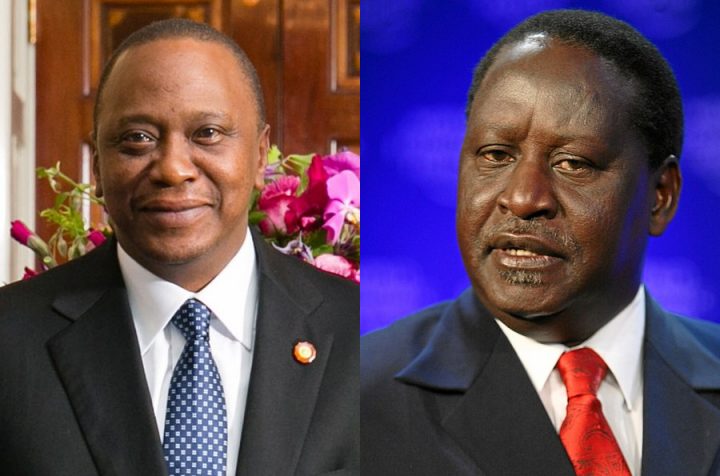

The IEBC itself also doesn’t have a result that reconciles. On Friday it said that Uhuru Kenyatta had won with 8,203,290 votes. Those numbers were meant to be based not on the numbers uploaded to the IEBC server, but by the results calculated in each one of the 290 constituencies that returned a member of parliament.

All the forms 34A were to be collected at the constituency level and added up on the form 34B. 290 forms 34B were then to be sent to Nairobi to the counting centre to be added up on the form 34C which gave the final result.

The final, authentic result under the constitution is the sum of the forms 34B, the IEBC website should reconcile to it however. But if you go to its website today, Uhuru Kenyatta has 8,218,271 votes, a difference of 14,981. This doesn’t make sense, if not all results have been uploaded then the number of votes on the website should be less than the number announced on Friday. The IEBC needs to clarify this urgently. None of this however puts the name of the winner in doubt, but it is a concern and gives room for improvement in 2022.

Pressenza has been monitoring these elections carefully for any sign of manipulation, and we have been unable to find anything to put these election results in doubt, and we would have loved for Raila Odinga, leader of the opposition, to have won after being robbed in 2007 and 2012. Such a result would have been a just reward.

Kenyan elections in the past have been so much worse. Polling stations in strongly polarised areas have reported impossible results in which more than 100% of the eligible voting population has voted. Incidents are legendary of bags of pre-filled voting papers being stuffed into ballot boxes before counting. And the final results announced by the IEBC often bore no resemblance to the results announced in the constituencies. Kenya can be given credit for resolving all of this.

But, we cannot say that the entire election process was free and fair.

The internal democratic processes of both the leading parties leaves much to be desired. Pressenza has learned of many cases in which the primary elections to select the candidates at all the lower levels of elected representation beneath the presidency were manipulated in which party officers sold the certificates of the winning candidates to others, with nothing more sophisticated than crossing out the winning candidate’s name and writing the name of the highest bidder instead!

On Election Day, well-funded candidates were able to stand outside polling stations and hand out food and money to voters if they would vote for them. Many voters sold their vote for a bag of flour or a couple of dollars.

The economic rewards for winning an election at any level are too good to be ignored by those who care nothing for their fellow Kenyans and are only interested in stealing as much as they can.

But we can be hopeful that Kenyan democracy is improving because the devolution of powers down to the local community which came with the new constitution of 2010 has led to a situation where ordinary people are starting to understand that their votes matter. In one county, Kisumu, of 35 council members standing for re-election with the same party as in 2012, 32 of them lost the primary election because the electorate could see how those councillors stole the money that should have been destined to infrastructure.

2017 will not witness a profound change in Kenya in which corruption is eradicated and democracy puts power in the hands of the people, yet we ask for too much if we hope for this because almost no country in the world can hold its democratic model up as a beacon of democracy – especially those Western countries who would inflict war on other countries in the name of democracy. Corruption is rife all around the world and the formal democracies we live in result in our elected representatives betraying the people and serving the interests of the economic global system whose insatiable greed knows no limits.

Yet, maybe we will look back at 2017 and see the moment in which Kenyans started to trust more in the democratic model, and started to exercise it more. Maybe it will be the moment in which the old paradigm of “divide along tribal lines and conquer the presidency” will die and a new kind of politics based on the wellbeing of people, on an economic model which serves everyone, on a social model which puts the concept of tribe in its rightful place as an “accident of birth” rather than the primary characteristic, will appear. If this happens, we will look back at 2017 as a truly historic year in Kenyan politics.