As in other aspects of socio-political culture, Chile’s experience of the late 1960s and early 1970s diverged significantly from other countries in Latin America.

On the one hand, hippismo (the hippies) and similar countercultural movements that captured the imagination of young people did so in a democratic, moderately plural society – albeit one whose days were numbered as polarisation and the success of Marxism ushered in the 1973 coup.

On the other hand, the divided politics of the era and the strong grip of social conservatism on both right and left in Chile meant that countercultural experimentation was often caught in the crossfire of class warfare, while also coming under fire from both sides.

Readers will take away different message from Patrick Barr-Melej’s excellent and finely researched Psychedelic Chile, timely in the 50th anniversary year of the Summer of Love, but by far the most interesting dimension of this book is the relationship between the Hippies and the Left.

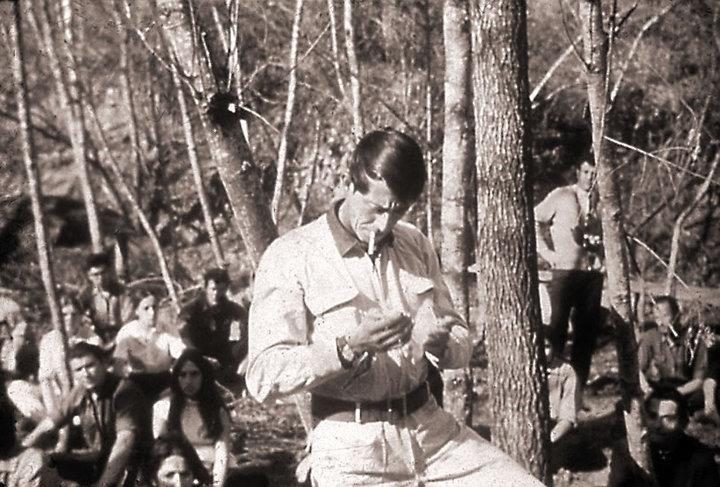

Focusing on the period from 1968–73, which was characterised globally as one in which the rise of the counterculture and youthful activism was at its peak, this book explores two currents at the heart of this phenomenon in Chile: hippismo, the loosely defined culture of long-haired dropouts with headbands and bell-bottoms who smoked pot and disregarded sexual conventions; and Siloism, a more structured movement organised mainly in Santiago around the teaching of an Argentine guru known as “Silo” (Mario Luis Rodríguez Cobos) and its associated group called Poder Joven that combined various political and personal philosophies in the quest for a defined path to self-enlightenment.

In a country such as Chile, both tendencies offer potent opportunities for research, but the author has confined his focus to explore three key propositions. First, entering Chilean history by way of the counterculture can tell us as much about the phenomenon’s foes as it can about these youths themselves. Second, as counterculture began to percolate through the youth scene, some of the values and attitudes it embodied began to seep into mainstream sectors of a younger generation that otherwise rejected what it embraced. Third, the media were critical in both influencing public opinion towards the counterculture – mostly in an ill-informed and prejudicial sense – but also reflecting it.

It is the first of these propositions that offers the most fleshy material for the political historian, mainly because of Chile’s unique circumstances in this period and their tragic consequences.

This was a time of intense polarisation in which both left and right defended mainstream cultural assumptions that were instinctively critical of the counterculture, albeit for different reasons.

It went without saying that the conservative credentials of the right and its links to the Church made it hostile to hippies and everything they stood for. Even the more moderate and progressive Christian Democrats, who played an important role in Chilean politics at this time, saw in the counterculture threats to the nation, culture and family.

It was on the left however, that hostility to the counterculture is perhaps less easy to understand and explain. In this period, the Left itself was going through something of its own revolution, ideologically and organisationally speaking, with the intensification of the Cold War, Che Guevara’s guerrilla (which undoubtedly resonated within the US and European counterculture), and the emergence in Chile of a new left subscribing to revolutionary vanguardism as opposed to an old left committed to traditional democratic incrementalism.

The tensions that these developments gave rise to resulted in Chile’s old left coming to power under new left banners – a democratic-revolutionary agenda – that incorporated many young people with their own ideas about what this meant in terms of behaviour, liberation and cultural transformation.

In short, the Left confronted countercultures while riven by disagreements about the nature of the social order that would eventually replace capitalism.

While some on the left advocated pluralism, anti-counterculture discourses provided Marxists a position of relative unity about the characteristics of the new model citizen, even if there were still generational differences among them.

As Barr-Melej writes: “ … governing Marxists and UP nevertheless preserved certain mainstream and bourgeois cultural outlooks and impressions that fell under the rubric of ‘family values’, existing in conjunction with an otherwise antibourgeois, antiimperialist, and anticapitalist revolutionary cultural-political project that saw public murals by young Communist artists, the massive publishing campaign of the state-owned publishing house (Editora Nacional Quimantú), the songs of Nueva Canción, expansive volunteer and ‘revolutionary’ pro-literacy efforts on the part of young activists, and other pursuits.” [p10]

By exploring this fascinating clash of cultures – the political versus the socio-psychological – Psychedelic Chile offers a novel and absorbing way in to this period of Chilean history. It is an important introduction to a phenomenon that is little considered by political scientists – the social conservatism of the Left – while also making up somewhat for an absence of literature that does not solely prioritise the participation of young people in class-based politics.

For many young people in that era, a culture of rejection of the old in which personal and socio-political liberation were largely indivisible – themes anticipated by the guru of the New Left, Herbert Marcuse – were at the heart of a vision of a new Chile.

In its own way, that was just as revolutionary as the failed experiment that Salvador Allende would embark upon.