By Binu Mathew

The morning papers bring me the news that Amazon founder and CEO Jeff Bezos is the richest person in the world. Actually he overtook Bill Gates for a few hours on Thursday as the richest person on earth as the Amazon share prices rose. Bill Gates regained his position as the richest person later in the day.

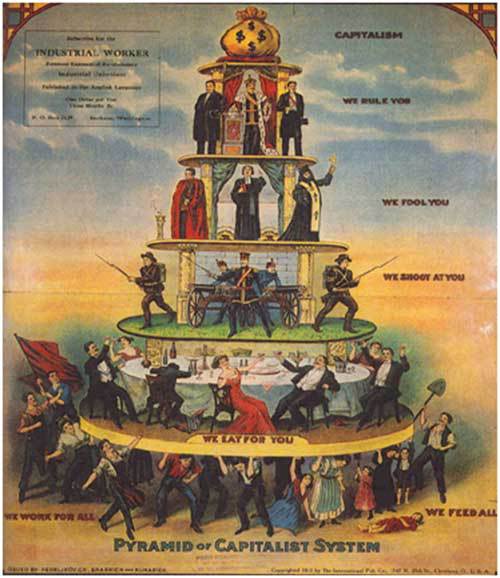

So what the heck we commoners should care about the wrangling for wealth at the top of the pyramid? Anyway, eight richest persons hold as much wealth as bottom 50 % of world’s population. That is 8 people hold as much wealth as 3.5 billion people hold collectively. According to world bank data 767 million people are living below the international poverty line, which is $1.90 per person per day. Should we be worried about Bezos becoming the richest person? Yes, we should. Why?

According to an estimate by Barclays Amazon is in the race to become the first $ 1 trillion company in history. In the race are Apple, Google’s parent company Alphabet and Facebook. All four are technology companies. What makes Amazon different is that it is a bridge between technology and real world. Most likely Amazon may win the race. Is it a good sign?

Bezos famously said “Your margin is my opportunity”. The Bezos business model is driving down the margin of brick and mortar stores and all other competitors. Using the technological knowhow and huge cash flow available to him it is possible for Bezos to drive out of business most of his competitors, be it small brick and mortar shops or even giant retail chains. There lies Bezos’ opportunity.

Why should we crib about hard working businessmen making good money? There is a danger. Joseph Tainter has pointed out in his book “The Collapse of Complex Societies”, as marginal returns become minimal, societies tend to make the system more complex to maximize profit. The same thing is happening now. The technological innovations like big data, artificial intelligence and robotics tend to make systems ever more complex. Whatever little marginal return on offer is funneled upwards the pyramid. That is why we see just eight people sitting comfortably at the top of the pyramid. Mind you, most of them are technological companies too.

This is not a new phenomenon. Civilizations have risen in history and collapsed. Most of the collapses followed the same pattern, as observed by Tainter. As the marginal returns become scarce, complexity also increases in way that it benefits only the elites of the society. Jared Diamond in his classical study “Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Survive” made similar observations too.

History of civilization itself is an ever increasing spiral of complexities, especially favoring the elites. It seems we are heading to the peak, with just 8 persons at the top. Even that number may decrease in the future.

As the pyramid reaches higher and higher and the bottom becomes ever more weak to hold the heavy weights at the top, the pyramid collapses. Those at the bottom are weak and they have hardly anything to eat and when they start to scramble for whatever they can find to sustain themselves, the collapse becomes inevitable. The social tensions at the bottom can take myriad forms like climate crisis, resource crisis like oil, water, food and ethnic, linguistic and religious strife and ever more increasing nationalism that mutates into fascism.

We are in a critical juncture in history. We are faced with collapse or revolution! Revolution can be bloody and can even be a bloodless. A revolution based on solidarity and communal sharing. It has to begin by boycotting and divesting from the elites at the top. Build an economy based on solidarity and sharing. Funnel the capital the elites accrued slowly down to the bottom. Strengthen the legs of the bottom majority. When we are powerful enough shake them down from their comfortable position at the top.

It’s not a dream. It’s within our grasp. If we get together as one global family, as John Lennon sang, “The world will be as one”.

Binu Mathew is the editor of www.countercurrents.org. He can be reached at editor@counatercurrents.org