by Jhon Sánchez

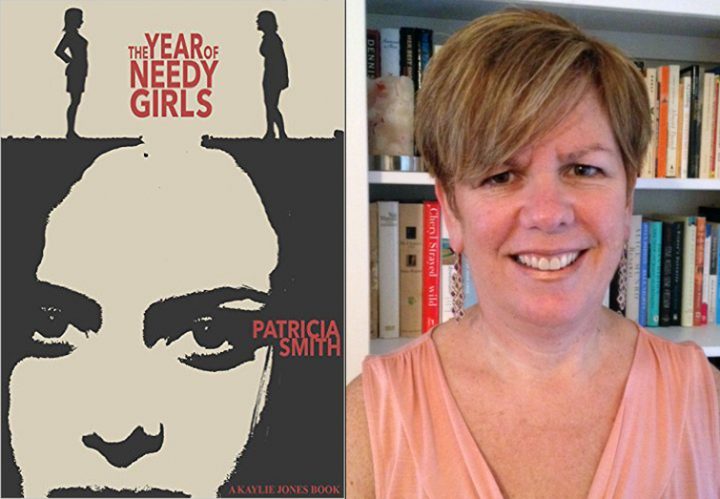

“The Year of the Needy Girls” by Patricia Smith is the kind of book I would give to my friend Jennifer. I’ve been a friend of Jennifer’s for three or four years now. Usually, I’m the only guy in her parties for lesbians. Now that I think of it, it would also be a great gift for my friend, Elvira, a Mexican teacher who is always preparing lessons plans, trying to divide herself among her students, her husband and her children. Anyway, it was the perfect gift for me, especially during Pride Month in New York. To talk more about this novel, I set up this interview with Patricia, and perhaps you, my readers, would share this book with more people to celebrate Pride.

Patricia, congratulations on your debut novel.

1) I usually don’t start with this question, but I would like to hear why you dedicated your book to all your students.

Well, since it’s a book about teaching, I thought that dedication was appropriate. I’ve also learned a lot from my students over the years! For the past 11 years, I’ve taught writing and American Literature, and my students have always been enthusiastic cheerleaders for me and my writing. I thought it was fitting to dedicate this first book to all of them.

2) Tell us about background and how this novel came about?

I’ve been writing since as long as I can remember— mostly nonfiction, actually — lots of essays and memoir-type work. But in the 1990’s, I was teaching 5th/6th grade in Cambridge, MA, when a 10-year old boy, Jeffrey Curley, was killed after being sexually molested by his next door neighbor. It was, of course, a horrible crime. My students were all unnerved—many of them knew Jeffrey, played Little League with him — and they were terrified that something like this could happen to them. At the same time, many of us in the LGBTQ community were nervous that there might be an anti-gay backlash because of the nature of the crime. But Jeffrey Curley’s parents were gracious about saying that this awful crime had nothing to do w/ homosexuality. Still — the fear lingered. Plus, I think I carried a lot of fear and nervousness about being a gay teacher back them. I always tell the story of the early days of Gay Pride, when we teachers used to wear paper bags on our heads so we couldn’t be identified. We were scared to lose our jobs. So, I think that I was carrying around those feelings w/ me and finally figured out how to tell a story that could explore those emotions.

3) You have interesting reflections about your career as a teacher throughout the novel, for example,

“When you were learning to be a teacher, taking graduate classes in methods, sitting in lectures about differentiation or the plight of the gifted child, no one talked about the most difficult thing —how you were going to love the kids you taught, how might even love them inappropriately or want them for your own, how you had to learn not to resent the parents.” Did you discover those thoughts in the process of writing or were they known to you before hand?

That’s a great question. I think many of those thoughts became conscious as I was writing the novel. And it was somewhere in the long process of writing the novel that it came to deal more with teaching. At first, I intended to write a novel about how homophobia hurt a family and then a small town. But it wasn’t until a late-ish draft that it became focused more on teaching.

4) Brazilian culture plays an important role in the novel. How did you get exposed to the Brazilian community?

I didn’t really. Most of what is in the book comes from research. I knew a little bit about the Portuguese immigrants who lived in Provincetown, but very little, really.

5) During your presentation at Bluestockings, you told us that you eliminated a character from your novel. Can you tell us more about that? How did you rebuild the story without this character? Is this character going to be recycled in another story?

I had a character, another teacher, named Maureen. She was a new teacher and someone Deirdre had a crush on. I thought that having Deirdre feel an attraction to another teacher would increase her guilt about what happened with Anna and would underscore the ways in which she was absent for SJ. But my editor suggested—and I think she was right—that Maureen’s presence in the novel took away from the central tension with Deirdre and Anna. I don’t think she’ll be recycled. But getting rid of her did take some work as she appeared throughout the novel.

6) Your novel has many layers. For me, it was about boundaries and also about personal and social prejudice. Can you comment on that?

I’m glad you think so. I definitely was hoping that those themes would emerge. I grew up in MA and as an adult, I had lived for a long while in Cambridge, a notoriously liberal city. But I was also conscious of a kind of façade that many people had —a liberal public attitude but a deep, personal prejudice. You know, when you’re on the outside of the mainstream, I think you also notice the ways in which the dominant culture is exclusive — for example, the ways in which our dominant culture still upholds heterosexuality as the norm. IT’s embedded in many of the traditions many of us like and celebrate. But our careless embrace of those traditions keeps many people on the outside, feeling as if they don’t have a place and don’t belong. Things are changing, for sure, but still — in my experience, many people give lip service to being inclusive until it matters personally to them. So I was interested in exploring that idea in the book.

7) At the end of your book, you thank some detectives that allowed you to understand the legalese, and a Sheriff that showed you inside the county jail. As an attorney, I thought you did a good job describing these aspects of the law. Can you tell us about your experience of doing this research?

That was so much fun! In my next life, I’d love to be a CSI! I love cop shows— Law and Order, CSI, etc. So I loved being able to talk w/ a police detective to figure out how Mickey might be caught by the police. And since I had no experience being in jail, I wanted to see what it might be like for Deirdre to spend a few days in jail—where she would be held, what clothes she’d be wearing (would she stay in street clothes or be given a jumpsuit, for example?). I have a good friend who was a prosecutor and is now a judge, and she brought me in to let me listen to arraignments, too, because my only experience w/ them was TV — and I wanted those scenes, however small, to ring true.

8) It seems to me that there are two axes where the story takes place: one is the school year, and the other is the tragedy of Leo Rivera. What are the functions of these events in the story? Did you plan that from the beginning or was it something you discovered later?

I’m not sure I understand, exactly. I structured the book around the opening of the school year, because as a teacher, it’s my favorite time of the year — and the true beginning of the year for me. So, I knew I wanted Leo Rivera’s disappearance to happen just prior to the start of the school year. And so normally, the fall, which was also Deirdre’s favorite time of year, would be the time when her life fell apart.

9) Your story is also about relationships. One of my favorite moments in the novel is the following: “It was this ability of Deirdre’s to ignore what was right in front of her, to go looking for some sort of approval from people she didn’t even know or have reason to care about instead of focusing on the love she did have, that drove SJ crazy. “Right,” she said to Deirdre now. “I love you.” And somehow, she thought, that makes me about as good as chopped liver.” Of course, we already know by then, that Deirdre has a different viewpoint on love. Is the problem with love that we love differently, that we express love in a different way?

IT could be. I think one of the biggest problems in relationships is our inability to communicate fully. That might have helped Deirdre and SJ — but truthfully, I think they were good for each other while they were together and it was time for them to separate and go their own ways.

10) Of course, we sympathize with Deirdre, with SJ, and we want the best for them. We want the political climax to be more open for everyone; we want, as readers, to be less prejudicial and become more tolerant. Can we achieve the same objectives by telling the story from the antihero’s point of view, let’s say Frances Worthington?

Hmmm…I don’t think so — but that’s an interesting question. I might have to play around for that!

Finally, next time you come to New York, would you like to invite you for dinner at my friend’s house. She makes fabulous food and the ladies are just great. Hey, before you answer… Jenny, can I bring someone really special to your house, next time?

For more information about the author please visit

patricia-smith.com

http://wtvr.com/2017/01/12/the-year-of-the-needy-girls/

http://www.virginiavoice.org/programcategory/the-writers-voice/ (Scroll down to Patricia Smith

“Holy War: Ramadan and race riots in Senegal,” by Patricia Smith. (Special Mention for the Pushcart Prize)

http://broadstreetonline.org/2017/03/from-our-archives-holy-war-ramadan-and-race-riots-in-senegal-by-patricia-smith/

http://broadstreetonline.org/2017/01/truth-teller-spotlight-patricia-smith/

https://kris-spisak.com/editing-interview-patricia-a-smith/

http://www.tristatehomepage.com/news/lifestyles/kaylie-jones-and-patty-smith/730090909?utm_medium=social&utm_source=facebook_WEHT_Local_Lifestyles

Jhon Sánchez: A native of Colombia, Mr. Sánchez immigrated to the United States seeking political asylum. He received a law degree from I.U. and an MFA from LIU. Currently, Mr. Sánchez is an attorney and enjoys traveling and cooking in his spare time. His publications in 2017 are available in Swamp Ape Review, Existere, Foliate Oak Literary Magazine, and 34thParallel . He is also contributor to “Letting Go: An Anthology of Attempts”, listed by BuzzFeed as one of the best anthologies of 2016. His work has been nominated for The Best of the Net Anthology 2016 and for a Pushcart Prize in 2015 and 2016. He was awarded the Newnan Art Rez Program for summer of 2017.