Renato Miguel do Carmo and André Barata 1 May 2017 for openDemocracy

Something relatively obvious took too long to be explicitly acknowledged in Portuguese democracy: that there are more points of convergence than of divergence among the leftwing parties.

We take a look here at the manifest failings of social democracy over recent decades, failings, that is, until the emergence of a political alternative convening different forces around a progressive agenda, as embodied by the configuration of the current Portuguese government.

Let us begin by considering the results of the latest legislative elections in the Netherlands. While the defeat of the far right may have ultimately allowed for some general relief, concerns over the long run continue to rise across the political spectrum.

For one, it appears that the non-victory of Geert Wilders can be attributed to the radicalisation of the nationalistic, anti-immigration rightwing party, led by the current prime minister. This means that part of the extremist agenda is beginning to permeate the traditional parties and to be normalised in political discourse and action. While such a strategy may momentarily stall the rise of the far right, it will eventually institutionalise and legitimise the latter’s agenda.

Another worrisome development is the downfall of the Social Democratic Workers’ Party, sunk to near political irrelevance when it had only just become partner to the government in the previous election. Similarities with the recent fate of the Greek socialist party can be seen here. Ironically, both fell prey to the same austerity politics they had previously devised: the former, as ideologue and impostor on a European scale, the latter as enforcer in its own country, against its own people. Subsequently, in France, the presidential elections also signalled early on that the socialist party candidate would not be a significant contender in the race.

Rather than rightwing politics (resilient to these collisions despite having driven the austerity agenda), it is social democracy which is succumbing to the shockwaves emanating from austerity. This should come as no great surprise, since austerity is in keeping with the political imagination of the right, but negates the very foundational essence of social democracy.

Many alarms were sounded at the time these choices were made on the nefarious consequences that this dissonance between the political imagination and the political agenda would bring about, including the electoral fragmentation of these political forces. Nevertheless, leaders like Mr. Dijsselbloem (still heading the Eurogroup) chose not only to ignore them, but bewilderingly to insist on a programme that had long been punishing several European nations, accompanied by his unfortunate advice to southern populations against wasting money on ‘women and alcohol’. What could possibly justify such bullheaded and blatant prejudice?

Social democratic myths and myopias

This is not such a straightforward question to answer. We bring four possible hypotheses to the table.

A first premise would be that social democracy, a fixture of many OECD countries, has been failing for at least two decades. Its original goal was to contain the growth of inequality through redistributive policies. Instead, the inequality gap has been rising in the majority of those countries since the 1980s. To the opponents of social democracy, it has failed because it made economies less competitive. Social democracy becomes untenable as soon as the west begins to lose its historical advantages in a global context of emerging economies. This diagnosis has become mainstream and is linked to the shift in the model of European construction after the Maastricht Treaty of 1992, as well as to the austerity politics of recent times.

A second conjecture refers to an overwhelming disconnect from social reality as the price to pay for the view that this is how the most competitive economies are created. Social democracy gradually dropped the social in favour of a merely economic view of reality, and notably the univocal adherence to that interpretation was achieved through the purging of alternative economic perspectives. The focus on the primacy of the economic, with at its core the quasi-fundamentalist grip of neoliberalism, shifted politics away from the reality of life (Lebenswelt), which in turn moved into an ivory tower draped in technocracy, built not to serve the people and the common good, but the interests of the most powerful countries.

The third hypothesis suggests simply that the sociological grounding of social democracy has been eroding since the 80s/90s, along with a decisively shrinking working class. In countries like the Netherlands, a cynical and ambiguous relation with Europe was stirred up in its place, in an attempt to counter receding electoral support. European institutions emerged as a new arena for the defence of the interests of the Dutch people: the protection of various national social groups leapt from factories and communities out to the European sphere. And it was in this context that austerity became an appealing policy, aimed primarily at the southern peoples, now pictured as having taken advantage of the northern countries and of living above their means.

The policy was thus designed to correct such misbehaviour and to protect the internal interests of the Dutch, aligning with those of Germans and others, as opposed to the non-conforming countries. However, as the election results showed, that narrative – spun by social democrat parties and one of its campaign talking points – failed to convince. In part, as we have noted, this was because it could hardly align itself with the original ideology, and voters ultimately perceived this as political treason. In addition to dropping the social dimension, the stance of some of these social democratic parties seriously compromised what democracy was left in EU institutions. This double defacement contributed, in turn, to the emergence of new political and partisan alternatives, in particular in the Dutch context, the Greens. The Greens proceeded to radicalise and integrate parts of the social democratic ideology into their programme, blending it with ecological, environmental, and social sustainability agendas.

The fourth hypothesis posits sheer cultural prejudice and intolerance against the southern peoples, which some of the so-called social democratic parties not only do not deny upfront, but connive with. The institutionalisation of this cultural prejudice set the tone, from 2010 onwards, of the political discourse of certain leaders and mainstream circles in European Union institutions, and only further instigated populism and nationalisms.

These four hypotheses on the decline of social democracy – having failed its purpose of cohesion; forgotten its social model; jeopardised European democracy; and fostered prejudice amongst various countries – identify interrelated structural trends which must be reversed and overcome. Many other arguments may follow in a debate which should increasingly occupy the public sphere, and which will hopefully bear fruit in the foreseeable future. The worst that could happen would be to bury our heads in the sand, waiting for the storm to be over. It is delusional to believe the storm will simply subside, that time heals all, and helps to forget all. It will not be so. It is truly fundamental for Europe that social democracy reinvent itself and reclaim its former initiative.

‘The contraption’ – dynamic coalition

The points of divergence are important, as they reveal that different alternatives are found in different spheres (which is a good thing).

In this context, the current government experiment in Portugal (the socialist party spearheads an alliance with two far-left parties, the Communist Party and the Left Bloc) suggests a path which might be followed in other European countries. The experiment, which has come to be known as “a geringonça” (“the contraption”) illustrates that social democracy is not necessarily doomed. On the contrary, it can expand and construct bridges, mobilising political connections among different forces around a progressive agenda.

The agreements at the origin of the current majority became the substance of an effective coalition process which is in essence being carried out. What has happened so far has thrown into relief something which, while relatively obvious, took a long time (too long) to be explicitly acknowledged in Portuguese democracy: that there are more points of convergence than of divergence among the leftwing parties. It further revealed something even more crucial: that the points of divergence are important, as they reveal that different alternatives are found in different spheres (which is a good thing); but they do not have to necessarily override the points of convergence. This methodological distinction at the core of the coalition was a further novelty of the negotiation process. Lo and behold, the left can act pragmatically without compromising the fundamental ideological principles of each party. Lo and behold, the left can act pragmatically without compromising the fundamental ideological principles of each party.

This government configuration has already run several risks successfully. The programme of income restitution and valorisation of people, enterprises and public institutions represents a structural departure from the previous model and that takes time to bear fruit. A year and a half after the government came to power, the country is patently much better. Disposable income has been progressively restored, unemployment is dropping continuously (currently 9.9%, and below 10% for the first time in 8 years), the public deficit has decreased to levels not fathomable only a few months ago (2%), growth tends to stay above 2%, exports remain strong.

Only the external debt remains at unsustainable levels which may (and will) eventually call for restructuring. Contrary to what many predicted after the rise of the left to power, not only did the country not collapse, but it is actually approaching ever closer to a sustainable economic and financial situation, and steadily moving away from the possibility of a second bail out. Following a profound crisis, and though much remains to be tackled in terms of social cohesion and inequality, Portugal currently lives in political and social stability, which is singularly remarkable in the European context. Portugal currently lives in political and social stability, which is singularly remarkable in the European context.

Reversing European drift

However, the continuity of this state of affairs cannot be ensured in an isolated manner. It is urgent to reassemble social democracy on its different levels, and this is done precisely by addressing the four hypotheses we have put forward.

Firstly, the coexistence of capitalism and social democracy cannot happen at the cost of the latter. Recalcitrant and growing intergenerational economic inequalities must be countered with policies that infuse equality into the very reproduction cycle of capital and which bring the regulation of inequalities in a broader intergenerational sense. An empirically well-informed theoretical reformulation is therefore in order, which can strengthen the social democratic agenda instead of demobilising it.

Secondly, in the European Framework, a model of economic and juridical integration must be restored, based on social inclusion and democratic legitimacy. A project of integration resting on indifference towards the exclusion it produces can only be carried out by more or less explicit coercive means, of which austerity politics are an example. This drift of the European Union must be reversed.

Thirdly, the same principle of socially inclusive integration must hold not only for European citizens, but also for the Union member states, which would preclude the current scenario of fiscal competition among the member states, as well as other forms of competition taking advantage within the common space of the Union of the disadvantages of its counterparts.

Against bullies

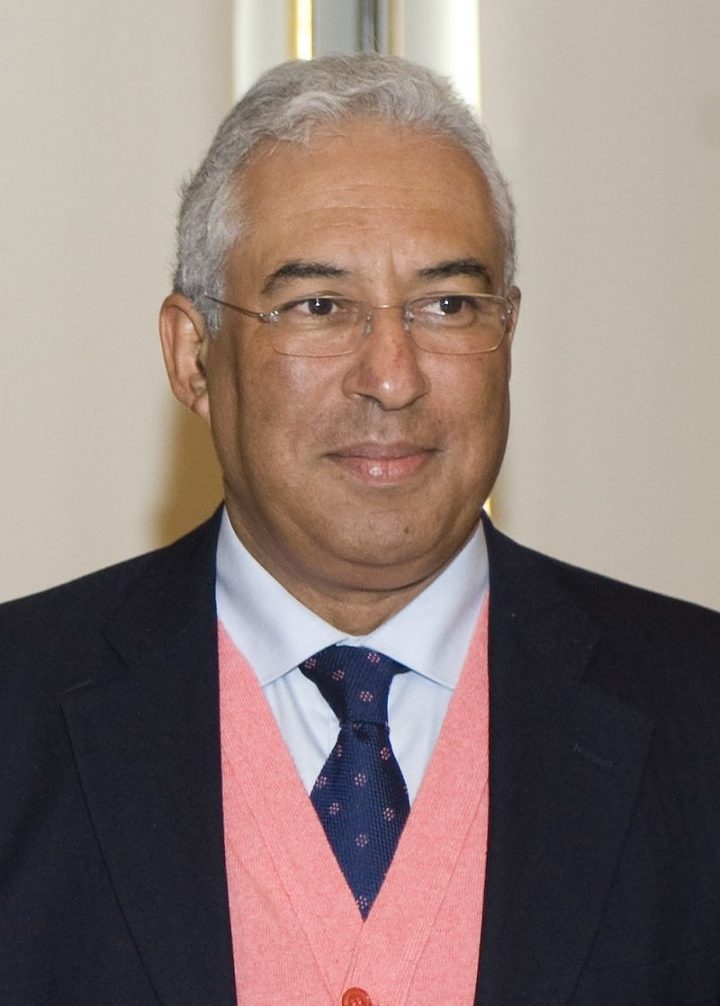

Finally, to counter the prejudice that poorly disguises the naturalisation of discrimination based on assumptions such as cultural superiority, it is as well to heed Gilles Deleuze and to become “worthy of the event”. By calling for the resignation of Dijsselbloem in a manner which was loud and clear to the wider European Union, the Portuguese prime minister António Costa made adequate reply to the stereotype, explicit or camouflaged, of rogue behaviour, inferiority, and self-indulgence tarring southern European countries, their peoples and cultures. While not alone, he was one of the first to protest and the most vehement, even eliciting some unhelpful response from his Dutch counterpart. This is the only sound way to democratically defeat populism. To be able to represent a people, adult citizens, with adult concerns and anxieties, autonomous citizens who wish to be represented by other adult citizens who take them seriously.

Dijsselbloem has attempted to downplay it as is his style, but this is far from the truth; in fact, he is simply a mimic, and it is the original that he mimics that must be ousted. There must be an end to this sort of European badmouthing, which has all the advantage of spreading like gossip, and none of the disadvantage of having to be done behind the target’s back; in other words, stereotyping, which was for many years the pattern of communication among the same politicians who used austerity as a non-inclusive European integration policy.

Dismissing the condescension of Dijsselbloem and his ilk (also found in Portugal) is also a lesson in how to defeat populism. To overcome the latter the most important tactic is to defuse it, to frustrate its decoys, to render it speechless, like the sulking, mumbling figure Dijsselbloem became. This achieves more against populism than a hundred observant declarations on its dangers.

This kind of patronising, which belittles and affronts the people, cannot be left unanswered. But what is in order here is not any populist, incendiary response, furthering exclusion, and making equal imbeciles of us all. It is instead a response from representatives who can articulate, at the right moment, with the right words, the sentiment of the fellow citizens they stand for. This is the only sound way to democratically defeat populism.

To be able to represent a people, adult citizens, with adult concerns and anxieties, autonomous citizens who wish to be represented by other adult citizens who take them seriously. And who can indeed rise to the occasion.

About the authors

Renato Miguel do Carmo is a sociologist at the Instituto Universitário de Lisboa.

André Barata is a political philosopher in the Universidade da Beira Interior.