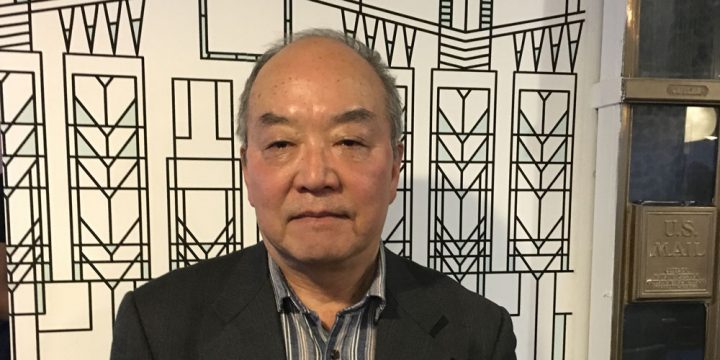

On Monday 27th of March, negotiations start on a treaty to ban nuclear weapons. Campaigners from the ban treaty network, ICAN, gathered on the 25th and 26th to plan their strategies and to bring everyone up to date with the latest information. The first panel on the Sunday session focussed everyone’s minds on why we are here and why a ban treaty it is so urgent and necessary, namely, the testimony of those who have witnessed and experienced first-hand the effects of nuclear bombs. Toshiki Fujimori, from Hiroshima, Japan, shared his experience with the visbly moved audience.

Let me share my experience of A-bombing.

When I was a 1-year-old baby, I was 2.3 kilometers from the blast center of the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima. Back then, my family consisted of 12 members: my grandfather, Father and Mother, 8 brothers and sisters and myself. As I was sick on that day, my mother was taking me on her back to the hospital. She was walking along the riverbank. As soon as she heard a low jet noise and tried to take shelter, a brilliant flash appeared and both of us were blown down to the dry riverbed by a fierce blast. Fortunately, there was a two-story house between the explosion and us, which I think prevented us from being exposed to direct heat rays.

When my mother crawled up on the riverbank with me in her arms, she saw an incredible sea of fire, with smoke and low cloud hovering above the city center. In the midst of the fire was a girls’ school, where two of my sisters attended. My fourth sister, who was a first grader of the school, was mobilized with her classmates to engage in building demolition near the ground zero area.

Fleeing from fire, my mother carried me and escaped to the Ushitayama hill side. My grandfather and third sister, who were at home as well as my father and eldest and second sisters who had been at work joined us there, but my fourth sister did not come. My two brothers who were elementary school students, and two other pre-school age sisters, were away from Hiroshima at the time, so they did not suffer the A-bombing.

The next morning, my father and eldest sister went down the hill to look for our missing sister. What they saw was a hell on earth: The city was full of rubble, blood-stained victims and dead bodies. Along the river they saw countless bodies of girl students. They must have tried to flee from the raging fire and jumped into the water. A timber basin was filled with corpses floating on the surface. They looked for her next day and also the following day, but she was never found.

I received a head injury by the bomb, which later festered. My entire head was bandaged, leaving only my eyes, nose and mouth. My family believed that I would die soon, just like other people who were dying one after another around me.

I was only a 1-year-old baby then, and cannot remember what happened to Hiroshima on that day. You may wonder how it is possible for me to talk about the A-bomb experience.

Every year when August 6 came, my mother called all of her children to sit near her. In tears, she told us about what had happened to Hiroshima in those days. Once I asked her why she kept on telling us her A-bomb experience, despite it being such a painful memory. She said, “Because I don’t want any one of you to go through such horrible experiences again.”

It was not only my mother who told us of her A-bomb experience. In my childhood, when I was resting with friends on the porch under some trees, an old man in our neighborhood would come and share his story of the atomic bombing with us. A teacher while I was in junior high school had a burn scar on her face from the A-bombing, and she would often speak to the students about her experience. When I was a senior high school student, I read many books, photo collections, poems and personal stories about the A-bombing in the library. I think that all these experiences and knowledge have enriched me and helped me to form my memory of the A-bomb.

Due to their painful experiences, many Hibakusha have closed their minds and their mouths. Their stories are too cruel to tell. The A-bomb damage is not limited to what happened on the August 6 and 9, 1945. The devilish A-bombings have been tormenting the survivors with long-term aftereffects of radiation.

My third sister lost her second son due to leukemia. It was in the summer of 1965, 20 years after the atomic bombing, that the boy suddenly lost appetite. She was frightened to see that the symptoms he developed were the same as she had suffered immediately after the bombing — high fever, bleeding from the gums and oral inflammation. After being taken to hospital, he was diagnosed with acute lymphatic leukemia. While going in and out of the hospital, he reached school age. But he could only go to school for 10 days and died in the winter of next year, aged 7.

My sister wrote in her diary:

“Alas, how stupid and ignorant I was! It was too late to realize the horror of the A-bomb. On August 6, 20 years ago, the atomic bomb seared my entire body by intense heat rays of thousands of degrees. It pierced through my skin and burned even my child, who was to be born 15 years later.”

The boy’s death was widely reported then as a case of the A-bomb effects on the second generation of the Hibakusha. She, too, died at young age of 56 of a liver disease which was often seen among the Hibakusha.

The atomic bomb persistently haunts the life of the Hibakusha and torments them until the end of their life. If this is not inhuman, then what can it be described as?

Most of the 170,000 surviving victims, whose average age is over 80, have various health problems. Even modern medical science cannot prove if their illnesses are attributed to their exposure to the A-bomb. Due to such difficulties, the Hibakusha are still forced to make complaints in court, seeking official recognition of their diseases as A-bomb related. Why are the Hibakusha forced to bear such a heavy cross until they die?

I call on you to take our appeal for “No more Hibakusha” seriously and take a bold step forward to achieve a nuclear weapon-free world without delay. Thank you very much.