By Jhon Sánchez

Marcia Butler’s book came to me like a miracle. I was editing a short story that elicits around the topic of music when ‘The Skin Above My Knee’ plopped into my mailbox. It surprised me that Marcia was a well-regarded oboist before becoming a writer. Her memoir uncovers simultaneously her life as well as her passion for music. It was a delight to read. I felt like she was a musical conductor directing the flow of my short story. I wanted to talk to Marcia about her book with the hope of being impregnated with her beautiful tone. Thanks Marcia for granting this interview here in NYC.

Marcia, tell us how the idea for this memoir came to you?

I hadn’t intended to write a memoir; rather, I was interested in writing essay about creativity. Those pieces eventually led me to write about my own experiences while performing as an oboist, which involved explaining the intense creative process that evolves during the act of playing music. Then the personal stories seemed to naturally seep into the mix – and voila! I realized I was, in some way, writing about myself the whole time.

What’s the story behind the title. More than one person has told me “What a beautiful title.”

The title is, finally, gently referenced toward the end of the book. Throughout my memoir, the reader gleans over and over that my mother was profoundly distancing. During a rehearsal for a concert, I emotionally collapsed when I realized that this area at my knee was the only manifestation of connection I could summon with regard to my mother. Just a patch of skin. And of course, this was a fantasy, but a very painful realization all the same. All this was brought to the surface during the rehearsal when Judy Collins sang the Leonard Cohen song Suzanne.

I love the opening because we enter an intimate moment in the life of a musician, but once I finished the book I thought, ‘Any chapter could have been an opening chapter.’ Do you think this is the kind of book one could start reading from any chapter? Among them all, each one so complete, how did you know the opening chapter was the one?

Most chapters could be standalone essays; certainly the music chapters and many others that tell my personal narrative. So theoretically one could dive in anywhere and still feel grounded in the material. This first chapter worked for me because it establishes the author in objective reality and as an expert at her job. The reader knows from the very beginning that this oboist is at the top of her field and is, therefore, completely reliable. At the same time, the chapter delves into the intricacy of the art form and the ephemeral nature of making music. We know where she will end up professionally, but the reader is, hopefully, intrigued as to what might happen to her on a personal level. The first chapter gathers together small teasers of what is to come throughout the memoir.

This was my subway book. I could read certain chapters between stops without having to close the book. How did you accomplish that? I love that brevity.

That came naturally, especially with the short, second person POV music chapters. Since this was the first major writing I’d ever attempted, I believe that short chapters suited my style. And I tend to be a “to the point” person by nature, so I suppose that is reflected organically on the page.

The book is divided between your personal life and your life as a musician. You write about music in a casual tone, intimate and beautiful. Do you have any advice on writing in such a manner?

Again – this pivoting device came to me intuitively. And as I looked back after writing the book, I realized that I was unconsciously attempting to further delineate the fact that I was leading two lives in real time. I don’t suggest any sort of construct or conceit to writers, but encourage them to allow the process of writing to finally tell them how the book wants to be laid out. That may sound “woo-woo”, but I do believe that the book takes the reins in a large way. The writer must know when to trust and when to steer.

As I was reading your memoir, realizing your life had been full of difficulties, from drug abuse to complicated family relations, I asked myself, what was the moment that allowed you to write about it with such tenderness.

For such realizations, there is no “aha” moment, but rather a slow burn. I’ve learned through the years, and sometimes with great difficulty, that compassion is necessary to fully understand not only others but also oneself. Everyone has deep hardships. But in memoir writing, anger and frustration is not a useful emotion from which to relay circumstances. It causes the reader to not trust the author who may have some axe to grind or feels the need to take the inventory of others. So I looked at my own life and saw how many mistakes I made; how I may have been unkind; how I surely could have been a better person. Writing it all down helped me to forgive myself. And others.

You managed to succeed as a musician even though you didn’t come from a family of musicians, or a wealthy family, and survived abuse and so on. Do you think this is a story of emotional alchemy? Is this intended to be a story for young musicians trying to accomplish their dreams?

Oh, I would love for young musicians to read my story and relate to the creative imperatives that drive an artist. Because when I was young, there was nothing else in the world I could even consider as a life path other than music. Few feel this. And even fewer actually attempt it and then succeed. That is not to say that I see myself as particularly special – it’s just that I have always felt that I was not fully in control of my artistic destiny, even when working incredibly hard at it. Surely young people might appreciate this and also might gain some inspiration to follow the gifts they have been given. So yes, my story is fundamentally about transformation, in music and in life.

You have an interesting life. What would your advice be for writers who don’t seem to have the same depth of experience?

My life has been varied in occupations – from musician, to interior designer, and now to writer. But I hasten to say that emotional depth is not outwardly manifested in a public way for most people. And this fact is something I encourage all writers to hold onto. Pain is pain. Struggle is struggle. Confusion is confusion. Love is love. Hate is hate. Desire is desire. And, finally, a story is a story. How the writer transforms these human experiences onto the page is not predicated by an outward, visible life. All you need is a heart, an imagination, a good vocabulary and some decent craft dials. And discipline helps a lot too!

How different do you think your story would be if you were a man?

This is such an interesting question! I’d like to say no difference at all, but that is a fantasy because of how society and families understand, interpret and deal with gender. The experiences of men and women are different due to societal constructs, both reasonable and terrible. What is inside us all as human beings, male or female, are universal human truths. That very fact is why I feel there may be hope in the world. Mental constructs and beliefs cannot change the essence of this truth. The topic is vast and would be a fertile conversation face to face.

I underlined many beautiful quotes in the book, but I would like to call attention to this one, “You still must conquer technical aspects, but that technique is now truly in service to the voice of the composer. The hierarchy has reversed, and the process is properly aligned. The music eventually shows you the way and becomes the solution. You feel like you’ve come back from the dead.” Would you say writing is similar to this description and/or how would it differ?

I believe one could apply this quote to writing (and all art forms for that matter), because there is always that moment of alchemy, when inherent difficulty transforms into the wonder of change and also a strange “knowing”. Somehow the hard rub of not getting the thing (whether music or writing) to behave like you want it to behave, falls into the background and stops being some awful and intolerable noise. Rather, it is now a distant rumble. And soon you can forget that it was even in your ears! This is true for the musician and the writer. The musician experiences this in endless practicing. For a writer, it is the entrenched editing process. When the cogs lock into place, there is great relief and pure joy.

Finally, I finished the book precisely as the 2 train opened its doors on 72nd street. Part of the story, especially the end, takes place around 74th street on the east side. It was another miracle. So please give me a hug.

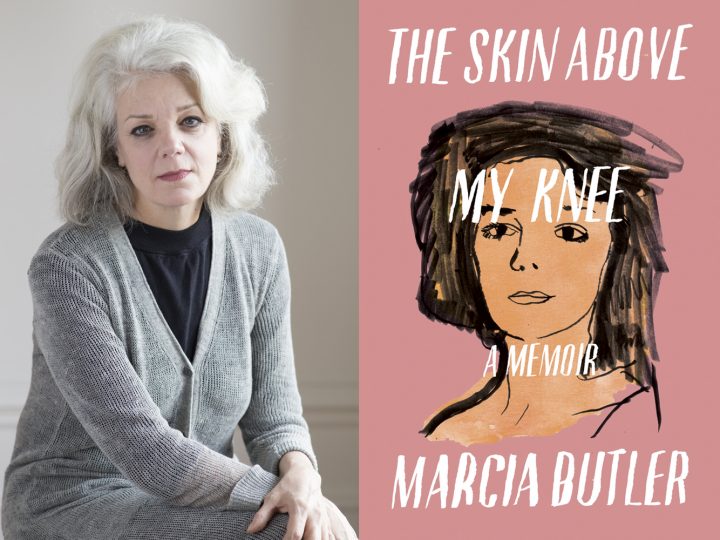

More information about the Marcia Butler and her work

The book is available in Amazon

Jhon Sanchez: A native of Colombia, Mr. Sanchez immigrated to the United States seeking political asylum. He received a law degree from I.U. and an MFA from LIU. Currently, Mr. Sanchez is an attorney and enjoys traveling and cooking in his spare time. His publications in 2017 are “The Vinegar Scent of Books,” available in Swamp Ape Review and “Acacia and the Thief of Names,” available in Existere. He is also contributor to “Letting Go: An Anthology of Attempts”, listed by BuzzFeed as one of the best anthologies of 2016, Nominated for The Best of the Net Anthology 2016 and for a Pushcart Prize in 2015 and 2016. He was awarded the Newnan Art Rez Program for summer of 2017.