Robert J. Burrowes

I sometimes wonder whether one of the ways in which ‘Amercian exceptionalism’ manifests is that many US scholars and others are unable to consider the contributions of those who are not from the USA. For example, I routinely read about studies of Martin Luther King Jr. and his associates (such as strategist James Lawson) in relation to nonviolence while the much more insightful and vastly greater contributions of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi on the same subject are largely ignored by US scholars (although not, for example, by Professor Mary E. King, one of the best in the field).

I have just read another book that falls into this trap: This is an Uprising: How Nonviolent Revolt is Shaping the Twenty-first Century written by Mark Engler and Paul Engler.

In this book, the authors try too hard to make nonviolent action fit into a model they have created by combining thoughts from a few (US) authors – essentially Saul Alinsky, Frances Fox Piven and Gene Sharp – to describe an approach to change based on structure-based organizing, momentum-driven revolt and the creation of prefigurative community. They then use a few case studies, all of which (including the campaigns of the US civil rights struggle) are from the USA except for the Otpor struggle to overthrow the Milosevic regime in Serbia and the struggle of the April 6 Youth Movement and its allies to remove the Mubarak regime in Egypt, to illustrate their argument.

So, as you now expect me to identify, one fundamental weakness of this book, obviously shared by each of the (US) reviewers praising it, is that the authors did not study the strategic thinking of Gandhi. This is obvious from the text but a quick search through the endnotes (which mention Gandhi’s An Autobiography and not one other document written by him) confirms it. Consequently, insights of Gandhi in relation to creating the empowered individual, community organizing (from village to national level) and the application of strategic nonviolent action are either ignored or attributed to those who either copied him (perhaps unconsciously), plagiarized him or, at best, reinvented the wheel many decades later.

Bizarrely, late in the book the Englers credit Gandhi: ‘to sustain his work over a period of more than fifty years, Gandhi used a full range of social movement approaches, including structure, momentum-driven organization, and the creation of prefigurative community…. But one of the most compelling aspects of his legacy is his interest in unifying all three.’ It is a pity that they did not study Gandhi so that they could explain in detail his own vital role, rather than those of the pale shadows who imperfectly followed him.

The incorrect attribution of Gandhi’s insights to others starts on page 3 of the book where Gene Sharp is credited with an ‘epiphany … that nonviolence should not be simply a moral code for a small group of true believers to live by’. But it is not exclusively the fault of the authors that they incorrectly attribute Sharp because Sharp himself claims credit for this insight and they cite his claim, from an interview conducted in 2003, on page 4.

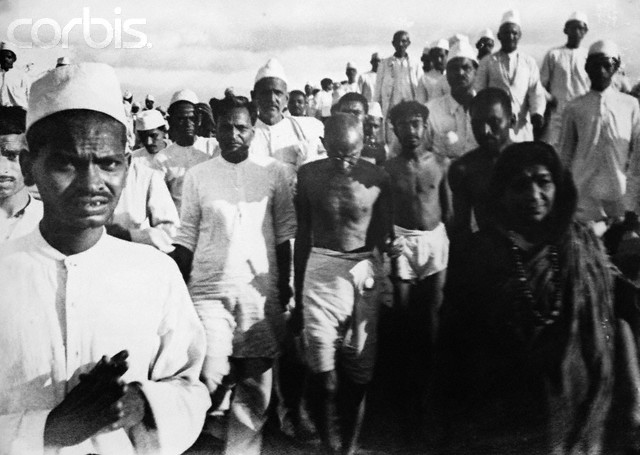

However, given that Sharp started his research into nonviolence three decades after Gandhi was mobilizing millions of Indians in major campaigns of nonviolent resistance to the British occupation of India and five decades after Gandhi was mobilizing thousands of Indians in campaigns of nonviolent resistance to injustices perpetrated on Indians in South Africa and during which Gandhi clearly articulated his awareness and acceptance of the fact that most of his fellow satyagrahis only followed nonviolence as a ‘policy’, not as a ‘creed’, Sharp is clearly wrong in claiming this insight for himself. For example, in Gandhi’s own words, from a speech in 1942: ‘Ahimsa [nonviolence] with me is a creed, the breath of my life. But it is never as a creed that I placed it before India…. I placed it before the Congress as a political method to be employed for the solution of political questions.’

Given that Sharp studied Gandhi during his early years of research into nonviolent struggle, my own inclination is to ascribe Sharp with a poor memory on this point, frightful though this may be (given that this is a perennial point of discussion in the nonviolence literature). Unfortunately, the book’s authors have been deceived by Sharp’s incorrect claim and they have not read widely enough to detect this falsehood.

But the failure to acknowledge earlier insights of Gandhi does not end there. In the Engler book, focusing on ‘concrete, winnable goals’ is described by David Moberg as an Alinsky principle and Rinku Sen, the authors say, claims that Alinsky ‘established a long-standing norm’ that ‘Organizing should target winning immediate, concrete changes’ that address the self-interest of those affected.

Now it may well be an Alinsky principle/norm. It’s just that Gandhi had articulated the same principle in his ‘Constructive Program’ booklet published in 1941 – the demands must be concrete, easily understood, and ‘within the power of the opponent to yield’ – and, of course, had acted on this principle in many of his earlier campaigns. It is manifestly evident, for example, in Gandhi’s list of eleven specific demands in relation to the Salt Satyagraha in 1930. Commenting on Gandhi’s shrewdness in this regard, Sarvepalli Gopal noted that these demands ‘were shrewdly chosen to win the sympathy of every social group in India’; moreover, they highlighted the injustice of British imperialism and constituted the substance of independence. And acknowledging Gandhi’s insight, Narayan Desai noted that people are more quickly and thoroughly mobilized when the issues are immediate and concrete.

As an aside: it was the failure of the Congress of the People held in South Africa during 1955, which adopted the Freedom Charter, to clearly identify the specific and concrete demands of ordinary Africans that explains why ANC campaigns during that decade failed to mobilize the increasing level of participation necessary to achieve the desired progress in the South African freedom struggle.

Yet another example of wrong attribution is the Englers’ discussion of how it ‘dawned’ on Sharp ‘that most people held flawed conceptions about the nature of political power’ regarding it as monolithic. On this point, Sharp’s debt to the sixteenth century French philosopher Étienne de La Boétie is clearcut but, once again, Gandhi had made the same observation much earlier than Sharp without the benefit of being aware of La Boétie’s work. As Gandhi explained it in 1941: a superficial study of history has led to the conclusion that all power percolates from parliaments to the people. The truth, he claimed, is otherwise: Power resides in the people themselves. In politics, he asserted in 1927, ‘government of the people is possible only so long as they consent either consciously or unconsciously to be governed’. In fact, he argued in 1920, a government requires the cooperation of the people; if that cooperation is withdrawn, government will come to a standstill.

One of the problems with much of the literature on nonviolence is that it is written by academics who have no (or absolutely minimal) experience of nonviolent action; consequently they often fail to appreciate what matters to a nonviolent activist ‘on the ground’. Having said that, there is no guarantee that the work of these nonviolence scholars is even sound in a theoretical sense. And that is a bigger problem.

Given it is one of the foundations on which the Englers’ book is based therefore, it is probably useful to briefly reiterate the fundamental strategic flaws in Gene Sharp’s work which were identified more than 20 years ago. In brief: it is not based on a coherent strategic theory, it makes no attempt to define the notion of will or to identify its strategic significance, it is based on the deeply flawed ‘scenario approach’ to strategy, it utilizes the popular misconception (promulgated by Basil Liddell Hart but also due to a misunderstanding of guerrilla theory) that the opponent has a weak point (or points) against which resources should be concentrated, it is based on Étienne de La Boétie’s consent theory of power (which is grossly inadequate for liberation struggles in the imperial world that has developed since La Boétie’s time), it fails to identify and explain the vital distinction between the opponent’s political purpose and their strategic aims, and it utilizes the pragmatic ‘win-lose’ approach to nonviolent action and entails a negative conception of the opponent both of which are inconsistent with the resolution of conflict. For a full explanation of these and other shortcomings in Sharp’s work, see The Strategy of Nonviolent Defense: A Gandhian Approach.

So what of the merits of the Englers’ book? The strength of this book is that the authors describe nonviolent struggles that convey a clear sense of the power of nonviolence and highlight some important lessons learned (even if they were learned anew by activists and even theorists unfamiliar with the literature on nonviolent action). This makes the book an inspiring read. The book also gives the general reader the chance to see the work of thoughtfully applied nonviolent action more clearly and to get a sense that it has theoretical underpinnings.

The weaknesses of the book are that it fails to accurately identify and then explain the actual origins of many of these theoretical underpinnings, as noted above, and second, it gives, perhaps unintentionally but most disturbingly, a rather distorted and simplistic impression of what constitutes strategy.

This is because the discussion of ‘strategic nonviolent action’ is reduced to just a few components of strategy, with most of the focus on the relationship between organizational structure, mass mobilizations and the creation of alternative communities and considerable focus on a few points about the way in which certain tactics are employed. These include those that involve disruption and entail sacrifice, those that pose a dilemma to authorities and the police, and those that polarize and escalate. There are also useful reiterations of why nonviolent discipline is so important, why the ‘diversity of tactics’ approach is misconceived and why violence and sabotage are so counterproductive.

But so many other vital components and aspects of nonviolent strategy that are far too numerous to even try summarising here are simply ignored. Even at the tactical level and despite touching on it in relation to the nonviolent blockade of the World Bank and IMF meetings in Washington DC in April 2000, the discussion includes the usual failure to clearly distinguish between the political objective and strategic goal of nonviolent actions (which is an endless source of torment for activists as their own example yet again illustrates). See ‘The Political Objective and Strategic Goal of Nonviolent Actions’.

Most unfortunately, because, as I have noted elsewhere, nonviolence is so inherently powerful that it can sometimes succeed despite a lack of strategy or even a bad strategy, the book essentially adds to the existing substantial literature that offers poor and, too often, incorrect strategic guidance for nonviolent struggle. It certainly offers nothing to those – such as nonviolent activists in China, Palestine, Tibet, Saudi Arabia and the United States – for whom only a sophisticated nonviolent liberation strategy has any real chance of success.

And we are not going to end war, halt the climate catastrophe (both critical imperatives at this point in history) or even have people behaving as if Black Lives Matter if our strategy does not account for every factor driving these deep-seated problems.

Anyway, in essence, my suggestion is this: If you want to read an inspiring account of the power of nonviolent struggle, then this book will suit you admirably: the Englers do this really well. And if you are interested in learning how to plan and implement a nonviolent strategy for your own campaign or liberation struggle (and learning about all of the necessary components of strategy in the process) you can find out how to do so on these websites currently being created: Nonviolent Campaign Strategy and Nonviolent Defense/Liberation Strategy.

If you also wish to be part of the worldwide movement to end violence in all of its forms, you are welcome to sign the online pledge of ‘The People’s Charter to Create a Nonviolent World‘.

As the Englers identify in their book’s subtitle, nonviolent revolt is shaping the twenty-first century. If this nonviolent revolt, in its many forms, is to have maximum impact it will require carefully designed and comprehensive nonviolent strategies that are thoughtfully implemented.

Biodata: Robert J. Burrowes has a lifetime commitment to understanding and ending human violence. He has done extensive research since 1966 in an effort to understand why human beings are violent and has been a nonviolent activist since 1981. He is the author of ‘Why Violence?‘ His email address is flametree@riseup.net and his website is here.