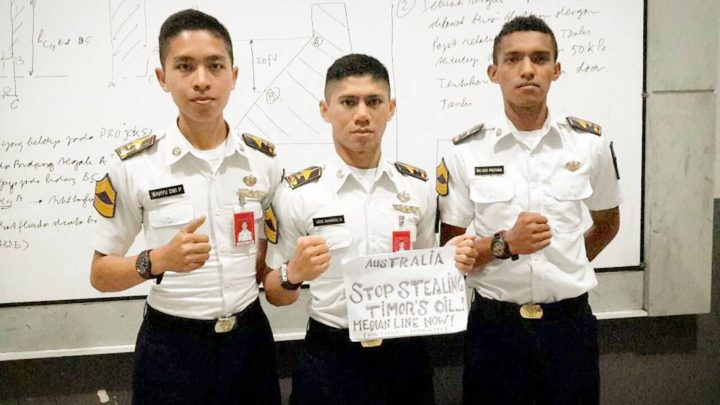

Australia is showing its worst side in its dealings with Timor-Leste over territorial waters claims that involve oil and of a lesser import to the big island, fisheries, by ignoring the smaller country’s legitimate rights which it intends taking to the international court.

According to the tiny nation of Timor-Leste, Australia has steadfastly rejected attempts to negotiate a permanent maritime boundary in the Timor Sea, site of plentiful oil and gas.

The country’s prime minister, Rui Maria de Araujo, journeyed to Washington recently to make a case at Congress and the State Department, asking U.S. officials to use their influence with allied Australia.

This could be a touchy issue given the USA’s stance on territorial waters disputes with China and the South China Sea and adjacent-waters like problems where Washington has repeatedly accused Beijing of coercive tactics against its neighbors.

Australia, like China, refuses to recognize the jurisdiction of an international court in The Hague that is geared up to resolve disputes under the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea.

What’s at stake is not just sovereignty or fishing rights in the Timor Sea, but billions of dollars from oil and gas. After East Timor gained independence in 2002, the two countries negotiated deals on sharing oil and gas revenues in three separate treaties. Those agreements gave an even split of revenues from the Greater Sunrise gas field, and granted Timor-Leste 90 percent of the revenues from one other field.

Strangely, one of the treaties includes a clause that calls for a 50-year freeze on negotiating any permanent maritime boundary between the two countries. Thus, Australia says the current arrangements have benefits for both sides and there is an agreement not to revisit the sea border issue.

Timor-Leste is making the moves toward a UN interjection because oil and gas revenues account for more than 95 percent of the tiny country’s income, and the tiny nation needs to clarify the legal status of the deposits in the Timor Sea to get production going.

“We stand by the existing treaties, which are fair and consistent with international law,” Australia’s foreign ministry announced in April after Timor-Leste disclosed its plans to take the case to the United Nations.

“If we use the principle of equidistance, we think that all these resources would belong to us,” Araujo has said. The fields are less than 100 miles from Timor-Leste and almost 300 miles from Australia.