‘The FBI’s credibility just hit a new low. They repeatedly lied to the court and the public in pursuit of a dangerous precedent that would have made all of us less safe.’

Following a high-profile attempt by the FBI and Department of Justice to force Apple to hack its own security encryption features, the federal government threw in the towel on Monday as it announced that it had successfully accessed information on the iPhone belonging to one of the perpetrators of the mass shooting in San Bernadino, California late last year.

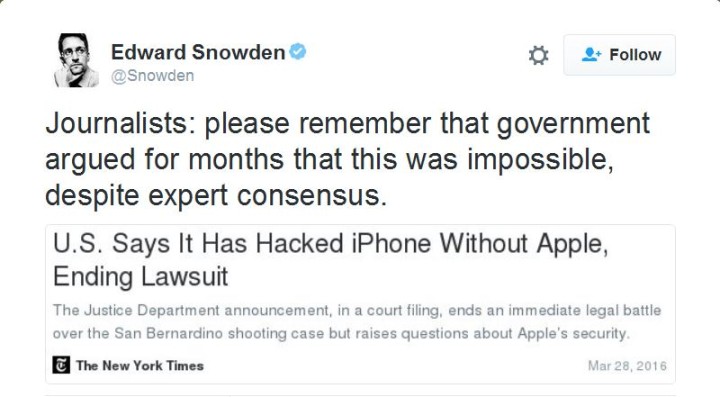

“Please remember that government argued for months that this was impossible, despite expert consensus.” —Edward SnowdenThe case that became known as Apple vs. FBI, which pitched digital privacy and civil liberties advocates against the federal government, created an international stir as Apple challenged a court ruling demanding that it create code that would allow federal agents to get inside the locked phone of Syed Farook, who along with his wife killed 14 people and wounded 22 others during a workplace shooting in December.

In a short court filing on Monday, the Justice Department said the government “no longer requires” Apple’s help in accessing the information. The DOJ requested the court order which instigated the legal battle to be withdrawn.

“Our decision to conclude the litigation was based solely on the fact that, with the recent assistance of a third party, we are now able to unlock that iPhone without compromising any information on the phone,” federal prosecutors said in a statement.

However, according to Alex Abdo, staff attorney at the ACLU, the government should not presume that advocates are going to drop their guard. “This case was never about just one phone,” Abdo said in a statement. “It was about an unprecedented power-grab by the government that was a threat to everyone’s security and privacy. Unfortunately, this news appears to be just a delay of an inevitable fight over whether the FBI can force Apple to undermine the security of its own products. We would all be more secure if the government ended this reckless effort.”

According to Fight for the Future, a digital and privacy rights group which helped lead opposition to the government’s case and applauded Apple for standing firm against the court order, Monday’s announcement should not come as a surprise given that the consensus among credible technical experts was always that the FBI always had likely other ways to bypass the iPhone’s security. The government’s real goal, according to the group, was not to access the data on one specific phone, but rather an effort to establish a legal precedent that could compel private companies to build backdoors into their products.

“The FBI’s credibility just hit a new low. They repeatedly lied to the court and the public in pursuit of a dangerous precedent that would have made all of us less safe. Fortunately, Internet users mobilized quickly and powerfully to educate the public about the dangers of backdoors, and together we forced the government to back down.” —Evan Greer, Fight for the Future

“The FBI’s credibility just hit a new low,” said Evan Greer, campaign director of Fight for the Future. “They repeatedly lied to the court and the public in pursuit of a dangerous precedent that would have made all of us less safe. Fortunately, Internet users mobilized quickly and powerfully to educate the public about the dangers of backdoors, and together we forced the government to back down.”

As the Guardian reports:

The development effectively ends a six-week legal battle that was poised to shape digital privacy for years to come. Justice Department lawyers wrote in a court filing Monday evening that they no longer needed Apple’s help in getting around the security countermeasures on Farook’s device.

“The government has now successfully accessed the data stored on Farook’s iPhone and therefore no longer requires the assistance from Apple Inc,” the government said. It then asked the court to vacate a 16 February court order demanding Apple create software that weakened iPhone security settings to aid government investigators.

The Guardian has reported that the technique used by the government has been classified.

Apple was fighting that order with a massive public relations and legal campaign. The company, America’s most valuable, argued creating such software would force the company to betray its values along with the security and privacy of all of its customers.

In response to the news, NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden offered a few key reactions via his Twitter account:

According to the Los Angeles Times,

Monday’s announcement could also have far-reaching consequences for local law enforcement. Police nationwide have long contended that data encryption allowed criminals to store information on smartphones to avoid detection. Thousands of the devices that have been seized during investigations in recent years currently sit idle in police evidence lockers. The Los Angeles Police Department has nearly 300 such devices, the department has said.

Though it’s unclear how the FBI gained access to Farook’s phone, the possibility that the agency found a way around Apple’s security measures could allow police access to similarly encrypted data in a much wider range of investigations.

Despite Monday’s developments, Gizmodo‘s Kate Knibbs explains that plenty of questions remain:

One enormous question remaining: What was on the damn phone?

And another: How will this case affect how the government pursues cooperation from tech companies in the future? This is not an end to the tension between law enforcement officials and companies with a business interest in safeguarding user data.

While the DOJ wasn’t able to use this particular case to establish precedent, the government filing is worded to very clearly emphasize that it was legally right to force Apple to help. The contested assistance, in this filing, is “mandated.”

Apple is still in active court cases with the government about assisting with seized phones, in New York, California, Illinois, and Massachusetts. Today’s withdrawal doesn’t make those cases go away. This is a way of pulling out of the conflict without admitting that the government’s legal argument sucked. It is a temporary détente at most.